Each month the Justice Center spotlights collaborative criminal justice/mental health initiatives that have received funding from the Bureau of Justice Assistance’s Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program (JMHCP). Center staff asks the practitioners in these programs to discuss some successes and challenges they have encountered in the planning and implementation process. This month’s profile is from Deschutes County, Oregon, a 2008 Implementation and Expansion grantee.

Program Summary

The Deschutes County Mental Health Court in central Oregon received an expansion grant to increase access to services for its target population: moderate- to high-risk adults who have pled guilty to a misdemeanor or felony crime, have a diagnosed mental illness or dual diagnosis of mental illness and substance abuse, and demonstrate a willingness to participate in the program as an alternative to incarceration in the county’s jail facility.

The expansion builds on a program in place since 2002 through a partnership among the Deschutes County Mental Health Department, the District Attorney’s Office, the Circuit Court, and the Alternatives to Incarceration Committee in Deschutes County. Under the expansion grant, the program, which serves a mostly rural community, has grown to include twenty-five participants at a given time–double its initial size. The mental health court has also increased awareness and understanding about mental health issues in the criminal justice system through educational programs aimed at attorneys and local law enforcement.

How did your jurisdiction realize that there was a need to respond to the prevalence of individuals with mental illnesses in the criminal justice system?

A multidisciplinary group of professionals developed the Alternatives to Incarceration Committee to discuss concerns about overcrowding in the jails and the increase in the number of individuals with mental illness who were incarcerated. In addition, many of these individuals were either being booked into the jail and released due to overcrowding, and thus not getting connected to needed treatment services, or they were being held longer than other inmates because of the severity of their mental illness. The committee recognized a need to develop a treatment court to address this population and improve linkages to necessary services.

How did your initiative capitalize on pre-existing relationships or partnerships in the jurisdiction, or build new ones?

There were already partnerships in place between the primary mental health and criminal justice agencies in the county, but having an ongoing committee that was invested in improving outcomes for individuals with mental illnesses and working together to develop a mental health court strengthened that alliance.

The mental health court built a very strong relationship with the District Attorney’s office. At first, the DA was reluctant to start the program. As we proved that the program could be successful in protecting public safety and reducing the use of jail beds, the DA became its biggest supporter. He has been the loudest voice in advocating for expansion and sustained funding, and has put in his time to keep the program running.

We are currently working on strengthening our partnership with the Veterans Affairs (VA) system. We recognize a high number of our military will be returning to our area in the spring of 2010. There is research that indicates that many will be returning with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and substance use issues, which put them at risk of involvement with the criminal justice system. We are developing subcommittees to work on implementing interventions pre-arrest, post-arrest, and post-conviction. Our mental health court program will be working directly with the VA on post-arrest options to provide extra support and treatment for this population.

How did you identify your program’s target population?

The committee recognized the need to start slowly and carefully with the implementation of the program. The DA initially agreed on only non-person misdemeanor crimes. As the program demonstrated high graduation and low recidivism rates, the DA was willing to broaden the eligible crimes to include felonies and some “person crimes,” with the exception of certain severe felonies, such as sexual assault, attempted murder, and murder.

The program initially targeted individuals with primarily Axis I, severe and persistent mental illness diagnoses, which could be in conjunction with a substance use issue. The program now allows a wider range of diagnoses, including but not limited to, PTSD, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance-use disorders, developmental disabilities, and brain injuries. A potential participant has to be able to understand the program requirements and be willing to comply with them. Our program is voluntary, but once individuals are accepted, they have to meet the expectations of the court.

What has been your biggest challenge and how are you addressing it?

Our biggest challenge as been meeting the treatment needs for substance use in the population with co-occurring disorders. We have fewer resources for substance use treatment, especially inpatient treatment. If participants’ substance use need is greater than their mental health issues, they require a lot of extra monitoring and support. This population also tends to face more serious criminal charges and is more likely to be terminated from the program.

Provide an example of a particular success your program has had to date, either in moving from planning to implementation or in showing an impact on an individual, group, or community.

Overall, we have achieved an 85 percent graduation rate and 13 percent recidivism rate since the program started in 2002. With the JMHCP grant, we were able to expand the program caseload from twelve to twenty-five participants.

The expansion grant also allowed the program to hire a full-time intensive case manager, which has been invaluable. The case manager has added support to clients, improved access to benefits for clients, increased partnerships with local agencies, and been able to be more responsive to clients’ needs.

This has also allowed the court coordinator to focus more on policy and programmatic issues, such as mental health court training for local DAs and law enforcement, which has increased the number of referrals to the program. In addition, the court coordinator was able to apply for and receive a state grant for long-term funding.

One case provides a good example of the program’s impact. A client with severe depression and PTSD entered the program for unlawful use of a weapon. By entering the program, the client was able to access needed treatment that she could not afford on her own. She reports almost a year clean/sober from alcohol, reconciliation with her daughter, an improved relationship with her partner, and mental health stability. This client successfully graduated in November 2009; her charge was dismissed and so she leaves the program with a clear record.

What steps have you taken or are planning to take to sustain your initiative?

We just secured additional funding from a state Criminal Justice Commission grant. This will add an additional year of funding to support our recent expansion. We continue to work with the county on securing long-term, stable funding.

Contact information:

Amber Clegg

541-322-7511

amberc@deschutes.org

********This application deadline has passed******** With support from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of…

Read MoreUnlike drug courts, which have been informed by national standards for 10 years, mental health courts (MHCs)…

Read More Building a Better Mental Health Court: New Hampshire Judicial Branch Establishes State Guidelines

Read More

Building a Better Mental Health Court: New Hampshire Judicial Branch Establishes State Guidelines

Read More

Apply Now to Join a Community of Practice on Police-Mental Health Collaboration Staff Wellness

Apply Now to Join a Community of Practice on Police-Mental Health Collaboration Staff Wellness

With support from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs’…

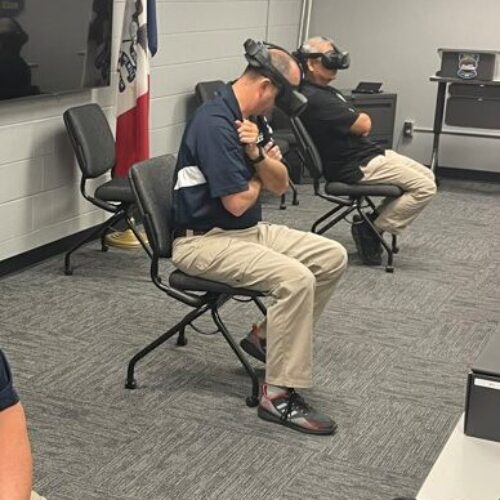

Read More Empathetic Policing: Mason City Police Department Launches Virtual Reality Training Program to Help Officers Better Understand Behavioral Health Crises

Read More

Empathetic Policing: Mason City Police Department Launches Virtual Reality Training Program to Help Officers Better Understand Behavioral Health Crises

Read More

Biden Signs Six-Bill Spending Package Funding Key Criminal Justice Programs

Biden Signs Six-Bill Spending Package Funding Key Criminal Justice Programs

On March 9, 2024, President Joe Biden signed a $460 billion spending…

Read More