Taking account of this new research, a number of states and jurisdictions have made significant changes to their juvenile justice policies and practices. To further this pursuit, this article offers guidance that draws from the most recent research and promising practices based on the new evidence. This article focuses primarily on juvenile justice policies and practices for youth returning to their communities from out-of-home placements (e.g., secure confinement, residential placements). The strategies presented here support the National Research Council’s recently published report calling for broad goals to which juvenile justice reform should be directed: holding youth accountable for wrongdoing, preventing further offending, and treating youth fairly.

The Reentry Continuum

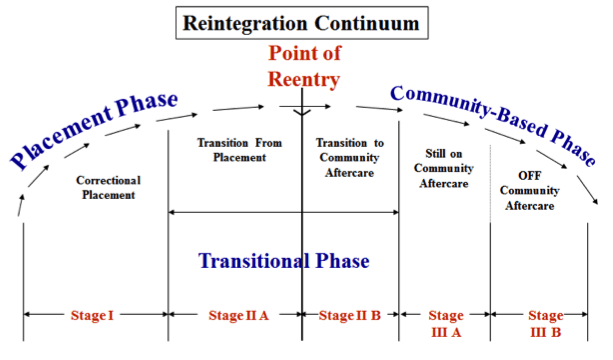

Best practices recognize that reentry begins at the time of admission to an out-of-home placement and continues beyond the youth’s release and reintegration into the community. This reentry continuum consists of three overlapping phases: 1) in facility, 2) the transition out of facility and into community, and 3) in community. The three phases overlap, and each requires its own set of components to work effectively. The continuum can be further separated into five mutually exclusive stages:

- Stage 1: the point of admission to an out-of-home placement

- Stage 2A: the latter portion of placement when discharge planning should be finalized

- Stage 2B: the initial period of community reentry/aftercare

- Stage 3A: the duration of community aftercare/supervised release following an initial period of adjustment

- Stage 3B: life without any formal or official justice system jurisdiction

Overarching Case Management

During the early 1990s, a federally funded juvenile reentry model known as the Intensive Aftercare Program lead to the development of Overarching Case Management (OCM), an approach that provides youth with a systematic continuity of care throughout the phases of the reentry continuum. A central aspect of OCM is the use of assessments to classify youth and match them to appropriate services. This practice includes developing a consolidated facility and community case plan that incorporates family and social networks, social controls, and services focused on risk and protective factors. Key OCM components in the community include graduated sanctions and incentives, realistic and enforceable post-release conditions, and links to community resources and non-correctional youth-serving systems, such as education, child welfare, employment, housing, behavioral health, and physical health services.

Six Critical Elements of Juvenile Reentry

By incorporating OCM in the policies and procedures of its programs, juvenile justice systems will be in a better position to implement the following six critically important programmatic functions in day-to-day practice:

- Assessment of Risk for Reoffending, Strengths, and Needs

- Cognitive-Behavioral Interventions

- Family Engagement

- Release Readiness

- Permanency Planning

- Staffing and Workforce Competencies

Reentry programs that include all six functions operating in tandem best exemplify broad, evidence-based programming. This article will briefly discuss each of these components and provide an example of a jurisdiction that is effectively implementing that component. The jurisdictions highlighted in this article are all current or past recipients of Second Chance Act grants. The jurisdictions are in the process of developing and implementing their reentry efforts, but they provide an excellent illustration of how each reentry function can be translated into practice. There is no one right way to implement these policies or practices, no one program or model to select. Rather, each of these jurisdictions have embarked on their own unique program design and implementation process that draws upon the growing body of research on what leads to positive outcomes.

Read each example below for more information:

Youth in out-of-home placements exhibit varying degrees of risk for reoffending, strengths, and needs. Most juvenile justice systems are now using some form of objective screening or assessment tool to identify youth who are at the highest risk to reoffend and make placement decisions accordingly. That said, youth who are assessed at low risk of reoffending may still be committed to out-of-home placements. For example, their needs may exceed treatment capacity in their communities, or the severity and gravity of their offense (which does not necessarily indicate they are at high risk of committing another offense) may warrant out-of-home placement. Youth assessed at high risk and who have identified criminogenic needs (e.g., antisocial attitudes, poor critical thinking skills, or negative peer group interactions) must have these needs addressed to lower their risk of reoffending. Strengths and protective factors, on the other hand, can mitigate the negative influences confronting youth. When appropriately identified, they can also act as facilitators of pro-social behavior, positive youth development, and law abidance. For these reasons, initial assessments and periodic reassessments are critical to developing supervision and case plans that are responsive to youth’s risks, needs, and strengths and that have the most significant impact on youth outcomes.

Example: Palm Beach County, Florida

In Palm Beach County, Florida, every youth committed to the Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ) receives a pre-screen Positive Achievement Change Tool (PACT) assessment. The PACT assessment determines the youth’s risk level for reoffending. Youth assessed as moderate-high or high risk for reoffending receive a full PACT assessment with 12 domains addressing: the youth’s current and past record of referrals, school history, use of free time, employment, relationships, family history, current living arrangements, substance abuse history, mental health history, attitudes/behaviors, and skills.

DJJ uses the PACT assessment from the intake process all the way through program placement and aftercare services. Youth receive a Community PACT (C-PACT) assessment prior to and after placement. A Residential PACT (R-PACT) is completed while in residential treatment. The assessments focus on the same protective factors and criminogenic needs that staff uses to further develop a plan to improve outcomes for youth. The PACT assessment identifies goals to be included in the Youth Empowered Success (YES) plan. The goals are developed with the youth and parent/guardian and are focused on the highest criminogenic need recognized in the PACT assessment.

Subsequent assessments serve as indicators of progress and improvement. Results from these assessments help DJJ staff determine whether youth are ready to be released from supervision or if they need additional programming to meet their needs.

Adoption of the C-PACT and R-PACT assessments has been widespread, setting the stage for more meaningful case planning and management. Since statewide implementation in 2007, more than 1.2 million C-PACT assessments have been administered. Since youth are assessed multiple times during each probation placement, these C-PACT assessments represent more than 300,000 unique individual youth. Of the C-PACTs completed during this time, approximately 14 percent indicated high risk for reoffending, 19 percent moderate-high risk, 16 percent moderate risk, and 52 percent low. There have been more than 69,000 R-PACT assessments conducted since its inception in August 2008. These R-PACT assessments were given to more than 15,600 youth placed in residential commitment during that time period. The assessment tools and results have been recorded in the Juvenile Justice Information System (JJIS), DJJ’s central database.

For more information, contact Shahzia Jackson, Senior Criminal Justice Analyst, Palm Beach County Criminal Justice Commission.

A substantial body of evidence points to the value of using cognitive-behavioral approaches with youth involved in the juvenile justice system. Broadly speaking, cognitive-behavioral approaches seek to develop pro-social patterns of reasoning by focusing on managing anger, assuming personal responsibility for behavior, cultivating empathy, solving problems, setting goals, and acquiring coping and life skills. They also build well upon what we know about adolescent brain development. When integrated into a unified continuity of care plan, cognitive-behavioral approaches can help facilities focus on what will happen after release to the community. What it takes to succeed in placement (namely, compliance with group living rules and requirements) is not what it takes to succeed in the community. For this reason, interventions should be geared towards preparing youth to manage his or her behavior through self-regulation and improved decision-making in community settings, rather than through fear of getting caught and its consequences.

Example: Texas Juvenile Justice Department

The Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD)’s rehabilitative strategy incorporates individual and group components that positively impact youth behavior. Established in 2007, it is an integrated, system‐wide rehabilitative strategy that offers various therapeutic techniques and tools that are used to help individual TJJD youth decrease risk factors and increase protective factors to be successful in the community. Evidence-based approaches of the rehabilitation strategy include: Motivational Interviewing, Cognitive Life Skills©, Thinking for a Change©, Aggression Replacement Training®, Why Try©, Seeking Safety, Functional Family Therapy©, and Parenting with Love and Limits®.

The implementation of these cognitive-behavioral interventions has yielded promising outcomes. For example, TJJD’s 2012 Treatment and Effectiveness Report indicated that youth completing ART® were rearrested for violent offenses and reincarcerated at a rate below the predicted rate. These youth had fewer referrals and admissions to the security unit while in high-restriction facilities. Behavior while in secure custody also improved: youth who remained in high-restriction facilities for at least 30 days after completing ART® had a 13-percent reduction in referrals to security and a 12-percent reduction in admissions to security compared to the 30 days prior to enrolling in ART®.

TJJD has also implemented Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), an evidence-based approach to addressing problem behaviors in schools. Since its implementation, TJJD has seen a decline in behavioral incidents during school hours and an increase in academic achievement.

For more information, contact Rebecca Thomas, Director of Integrated Programs and Services, Austin Office, Texas Juvenile Justice Department.

Example: Virginia Department of Juvenile Justice: Tidewater Reentry Program

The Tidewater Reentry Program of the Tidewater Youth Services Commission (TYSC) in Virginia uses cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with youth and young adults who are at moderate-to-high risk for reoffending and who are referred to the program by parole officers. TYSC determines risk levels using the Youth Assessment and Screening Instrument (YASI).

Each youth is assigned a reentry case manager and TYSC clinical staff administers interventions such as Stages of Change and Aggression Replacement Training. TYSC designed the program to emphasize pre-release services so that a framework and plan are in place for the client and family. Because Virginia Juvenile Correctional Centers (JCCs) are 100 or more miles away from the Tidewater area, disruption to the parent-child relationship is common, and families are often unable to visit or participate in services to prepare for their child’s return. To help address this issue, reentry staff travels to the JCCs to visit each youth referred to the program. Using motivational interviewing techniques, they seek to engage the youth and build a rapport with them to gather as much information as they can to assess the youth’s strengths and needs.

TYSC staff use CBT to help youth identify and understand their own thinking before they committed the offense, during the act of offending, and how they currently view the offense. Staff helps youth identify potential risk factors and compare their perspective with what is identified on the YASI. TYSC staff elicits feedback from youth regarding their plan of action to increase their protective factors and to become a productive member of society. The same process is used for family engagement.

Each youth receives a case plan that is developed using results from the YASI while at the JCC. Roughly 95 percent of clients indicate aggression/violence as a priority area. The client will then be recommended to receive Aggression Replacement Training (ART) upon release. ART’s three components of social skills training, anger control, and moral reasoning are taught using modeling, repetitious behavioral rehearsal, cognitive restructuring, and social learning. The program teaches youth strategies for resolving conflicts, managing one’s emotions, and making ethical decisions.

Substance use may also be identified as a high priority area in the comprehensive reentry plan. Although the youth generally have completed substance abuse treatment while committed, youth who have had a history of prolonged substance use may need additional treatment while dealing with the challenges of reentry. Youth are then referred to relapse prevention, which emphasizes helping youth change positive attitudes about drug use and how to select pro-social activities and associations. The “stages of change” are incorporated into the approach to address issues of inadequate motivation, resistance, and defensiveness. The counselor identifies, and accepts, the youth’s assessment of where he or she is on the continuum of change and works from there. Coupled with motivational interviewing, this approach improves the client-counselor relationship and increases the likelihood that the client will move forward through the stages.

Treatment interventions are paired with accountability measures through a significant amount of direct contact (several hours per week by phone or face to face), 24-hour emergency availability of staff, and graduated sanctions/rewards (including electronic monitoring). Random urine drug screens are used, as well as maintenance polygraphs for those in sex offender relapse prevention services.

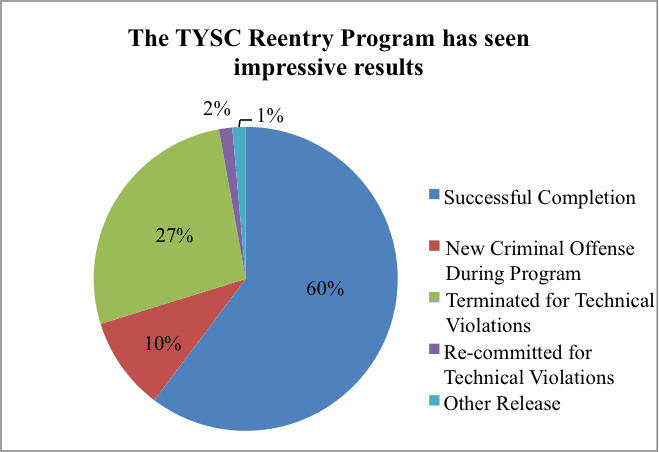

The program has yielded impressive results:

- Of the 141 youth who were discharged from the program, 60 percent successfully completed the program.

- Clients who received ancillary services using motivational interviewing, CBT, and ART model also exhibited positive results:

- Of the 46 youth who completed substance abuse relapse programs, 28 (or 60.8 percent) completed the reentry program successfully.

- Of 14 clients who completed in-home counseling services, 13 (92.8 percent) completed the reentry program successfully.

- Of 6 clients who completed ART, 5 (83.3 percent) also completed the reentry program successfully.

- Of 8 clients who received sex offender relapse services, 7 (87.5 percent) also completed the reentry program successfully.

For more information, contact Linda Filippi, Executive Director, Tidewater Youth Services Commission

The support and protection of parents, family members, and caring adults is essential for any child, especially children in trouble with the law. Regardless of whether a youth returns to the care of a family member, foster parent, or group home, the presence or absence of family support will play a significant role in his or her development. Some families are well equipped to support a youth in an out-of-home placement, while others are less well equipped to do so for any number of reasons. Juvenile justice agencies and their partners should use the time a child spends in out-of-home placement to strengthen relationships between committed youth and their families and build a network of pro-social support for the youth. Officials should identify and cultivate family support from the time a youth is committed.

Example: Washington State Juvenile Rehabilitation

In Washington State, family engagement is a key component for a juvenile justice youth’s successful reentry back into their homes and communities. Washington’s Juvenile Rehabilitation (JR) parole model, Functional Family Parole (FFP), is a family-focused parole supervision model that recognizes the vital role of family in preventing youth from reoffending. FFP is evidence-based and grounded in the same principles of the Functional Family Therapy model.

Parole counselors meet with the youth and their family in their home at times that accommodate the family’s schedule. Using FFP principles, parole counselors project an attitude of respect, develop a balanced alliance with all family members, and strive to reduce negative feelings, such as blame, in interactions among family members. This approach helps families improve how they work together to accomplish family goals and reduce the youth’s risk of reoffending. Families are taught strategies to support and reinforce the positive changes their child has made.

JR collects surveys from youth and families completing parole supervision inquiring about their experiences while working with the parole counselor. Overall, many families report that they are getting along better with their son/daughter on parole and that the youth is performing better in the community than they were before being involved in FFP.

FFP was shown to be positive and effective in interim outcome studies and preliminary outcome evaluations by Indiana University. In 2011, the Research and Data Analysis Division of the Department of Social and Health Services in Washington State, in collaboration with JR, published a study on the effects of FFP on two groups: youth released from residential confinement to FFP supervision and youth released with no parole aftercare services. The study found that youth in the FFP group were significantly less likely to be rearrested in the nine months following release and were more likely to be employed (and to earn more money) than the non-FFP group.

For more information, contact Laurie Hart, FFP Program Administrator or Kathleen Harvey, Administrator for Reentry, Transition and Education, Juvenile Rehabilitation.

Example: Lancaster County, Nebraska

Lancaster County, Nebraska, began its reentry work with a Second Chance Act Juvenile Demonstration planning grant. Based on risk assessments and youth interviews completed during the planning phase, the planning team knew that parent involvement was going to be the key to the success of the project and, more importantly, the success of youth and their families. Awarded a second grant for implementation the following year, the reentry project utilizes community-based organizations to provide reentry services that target youth’s strengths and needs.

To better foster families’ engagement in the reentry process, one partner organization, Families Inspiring Families, provides a family advocate who begins working with family members from the time the youth is committed to the Youth Rehabilitation and Treatment Center (YRTC). The family advocate is available to the family during the court dispositional hearing when the youth is ordered to the YRTC as well as at the Lancaster County detention center to meet with families of youth. Families Inspiring Families also offers family groups on various nights at the detention center, providing a forum for parents to learn more about the YRTCs, what it means to have a child there, and from one another’s experiences.

The family advocates are selected based on their direct experience having a child at the YRTC, so they are familiar with the process as a family member. The advocate is also trained in effective parenting strategies and working with the family on preparing for the youth to return home.

Families have identified communication with system providers as one of the biggest stressors. The family advocate works together with transition specialists funded through the grant to ensure family team meetings occur monthly with both a family member and youth present. The purpose of the meetings is to develop a plan for a seamless and successful transition back into the community for the youth.

Funding through the Second Chance Act has allowed for youth to have a reentry team consisting of a transition specialist, family advocate, mentor, and school liaison. This team is dedicated to assisting the youth and family from the moment the youth enters the YRTC through return to the community. In the first 6 months of grant funding, 75 youth were referred to the program.

The program was designed as a result of a broader juvenile services comprehensive community planning effort in Lancaster County. Concern regarding data showing a high rate of youth returning to the YRTC’s prompted the Second Chance Act juvenile reentry demonstration planning grant in partnership with the Office of Juvenile Services (OJS) /Department of Health and Human Services. Since that time, state legislation (LB 561) has shifted the function of community-based supervision after release from YRTC. OJS now only operates the facilities and Nebraska Probation Administration provides reentry planning and supervision. Lancaster County receives continuing technical assistance from the National Reentry Resource Center.

The factors that influence the decision on release from placement, the entity with the authority to make release decisions, and the process used to plan for release vary enormously across the country. Some youth handle group-living settings exceedingly well, but this does not necessarily translate to success when they return to the community. Other youth have difficulties adjusting to such settings, but that does not mean failure upon release is likely. What it takes to succeed specifically in placement is not necessarily what it takes to succeed back in the community. Even the definition of success is not the same: success in placement typically involves following the facility rules, while success in the community is much broader and can range from not reoffending to educational achievement. It is important, therefore, for the facility and community staff—and their community partners—to create an effective plan that is inclusive of the supports the youth will need to be successful in both settings.

Example: San Francisco Juvenile Collaborative Reentry Team

The San Francisco Juvenile Collaborative Reentry Team (JCRU) is illustrative of one effort to create a partnership around release. This unprecedented partnership between San Francisco Juvenile Probation, the Public Defender, the Center for Juvenile and Criminal Justice, and the Superior Court of California was developed to improve the outcomes for youth returning from long-term commitments. JCRU is a fully staffed probation unit that works with a dedicated reentry court and attorneys to develop and oversee intensive reentry plans for youth returning from a range of long-term commitments, including out-of-home placement and San Francisco’s Log Cabin Ranch, a post-adjudication facility.

JCRU’s reentry plans are developed and approved by the reentry court up to 90 days prior to the youth’s return. The early planning allows for a seamless transition back to the youth’s community and family. JCRU youth do not return until all of the elements of the plan are in place and vetted by the entire team. Components of the plan include family relationships, housing, education, employment, mental health, substance abuse treatment, and social recreation. Each one of those components must be addressed before a youth can return home. The JCRU team also uses standardized tools such as the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths Assessment and Youth Assessment and Screening Instrument in the development of reentry plans.

JCRU eliminates the adversarial dynamic of the courtroom and replaces it with one that is totally unified behind the child and family. Because JCRU’s reentry plans are developed and approved by the entire JCRU team including the attorneys prior to the court hearings, court time is used to support the child and reinforce his or her success. This model has proven to be effective. In the first three years of the program pilot, which focused on youth committed to out-of-home placement, probation violations fell by 14 percent, new subsequent bookings by 17 percent, and new sustained petitions decreased by 57 percent. In the first 6 months of the expanded JCRU model, recidivism among youth served fell 8 percent.

The role of the facility staff is critical to JCRU’s success. At Log Cabin Ranch, staff recommends youth for graduation and the JCRU team, in turn, reviews the recommendations. This collaboration between the JCRU and Log Cabin Ranch helps ensure youth graduate when they are ready and not based on the number of days spent in placement. Perhaps the most valuable outcome for JCRU has been the strengthened relationships among probation staff and the various placement sites. Probation staff communicates regularly with the placement staff to identify the release date and ensure proper planning beforehand.

For more information, contact Sara Schumann, Director of Probation Services, San Francisco Juvenile Probation Department.

Permanency planning is an essential component of sound child welfare practice. It helps ensure children and youth have strong, sustained connections with positive, nurturing adults in their lives. It calls for the use of a paradigm that is fundamentally strength based and family centered. For older youth, it takes into account their future beyond the period of placement, and as they leave adolescence and enter early adulthood, when connections to pro-social adults and peers and a sense of belonging to a positive community are key. This approach is starting to take hold in juvenile justice practices, including in developing strong plans for reentry that create supports that last long after system involvement has ended. Consistent with what we now know about adolescent brain development, policies and practices that address permanency considerations into the early and mid-20’s are likely to have a significant impact on both recidivism and other outcomes.

Example: North Dakota Division of Juvenile Services

The North Dakota Division of Juvenile Services (DJS) has long integrated permanency planning in its practices. One of the core principles of the agency’s intensive case management process, permanency planning has always centered around the same basic idea: work is not finished until the youth is restored to a community-based placement and has a reasonable expectation for a successful future. In addition to the work of the state youth corrections agency, permanency planning requires substantial commitment across youth services systems. In North Dakota, the juvenile courts, child welfare system, and private provider networks share a common value concerning the importance of permanency. Best practice guidelines, interagency agreements, funding strategies, cross-training, and a host of other relationship-building efforts contribute to statewide partnerships that for the most part work together to put the needs of youth and families first. Communication is a key strategy. Consistency in the leadership message is also important.

North Dakota juvenile courts are able to transfer legal custody of youth to the DJS, as a dispositional option in delinquency cases. Case management is a continuous process, from the moment care, custody, and control are removed from the parent and transferred to the state agency, until they are returned to the parent. This structure allows permanency planning for each youth to begin immediately upon their commitment to the agency. Each youth is assigned a case manager who meets with the youth and family on the day of commitment to discuss the goal of reunification and the development of a plan that will meet the needs of the youth. Youth enter a reception center and undergo a 14- to 21-day assessment process. Staff utilizes a number of tools designed to form the basis of a comprehensive treatment plan. Criminogenic risk, mental health, substance use, educational /vocational needs, and family needs are among the factors considered. Treatment plans are reviewed every three months to assess progress and to develop new goals. While the youth are working on their own personal goals, the family is requested to assess and treat their needs. Families are referred to services that are appropriate to needs identified with the goal of reunification. Youth who require some sort of out-of-home care before returning home are placed in a setting according to their specific needs, such as foster care, residential group home or psychiatric residential care, or treatment at the youth correctional facility. The case manager meets the youth at least once per month while the youth is in care, as well as meets or makes monthly contact with the family to make sure all needs are being met. A multidisciplinary Child and Family Team meeting is held every three months to review the treatment progress of the youth and family and to assess additional needs. The Child and Family Team meeting brings together the youth and family, along with the service providers and any additional supports.

Youth are supported as they transition from placement to home. Home may be with a parent, grandparent, other family member or another home agreed upon by the youth and family. Case management and community-based services are provided. Cases are supervised for several months prior to the end of the custodial order. Court-ordered jurisdiction can be extended until the goals of the plan are achieved. All plans have a concurrent plan in place as a back-up to the primary plan. Sometimes, there is even a third plan. Youth over the age of 16 receive independent living education. In very selective cases, a youth may be a candidate for living independently after the age of 18. In those cases, a plan with services is implemented so there are strong supports in place.

Youth and families are able to continue with services in the community once the youth is no longer under the custody of DJS. Although most youth and families do not maintain contact with the agency following the expiration of the court order, some do. All youth have a plan in place at the end of custody based on their continuing needs. This might include enrollment in school, appointments for medication management, mechanisms for prescription refills, established relationships with other service providers or agencies, key supportive individuals who can play a meaningful role in their lives, or contacts concerning potential employment. As a result of the connections that are emphasized during the service phase, permanent connections are often established and maintained.

For more information, contact Lisa Bjergaard, Director, ND Division of Juvenile Services.

Implementing policies and practices that adopt a continuity of care and an OCM approach requires thinking differently about how staff are used, what qualifications are required, what skills staff need, how training should be approached, and on what basis staff performance should be evaluated. Veteran staff may not always be receptive to all the principles and functions required to conduct these interventions well and with fidelity to the models, especially if it is a new way of doing business, and it can be very difficult to make personnel changes in many jurisdictions. Additionally, turnover is not uncommon in juvenile justice systems, making it difficult to maintain a dedicated and trained staff. Finally, resistance to change among staff can quickly affect morale and make full implementation more challenging.

Juvenile justice management must exhibit a strong leadership role in any new approach and work with staff to understand the reasoning behind the changes and the potential impact of their new approach to working with youth. Providing ample training opportunities and support will ensure that staff is able to adequately perform their duties and has bought in to the new approach.

Example: New Jersey Juvenile Justice Commission

Release planning for youth with sex offenses is a challenging area of practice. Many youth cannot return home or are ineligible for placements due to age, risk factors, Megan’s Law status, or other factors that result in temporary and failed reentry plans. Through a Second Chance Act Juvenile Demonstration grant, the New Jersey Juvenile Justice Commission (JJC) has enhanced its reentry services for male and female youth with sex offenses who were released on parole and or are on probation status by:

- Procuring sex offense-specific treatment

- Providing training for clinicians to treat sexually abusive youth

- Increasing individualized services

- Increasing employment and career opportunities

The JJC’s major accomplishments through the grant include the sponsorship of the Juvenile Sex Offense Training and Consultation Program. First initiated in 1997, the Training and Consultation Program was modeled after the New Jersey Task Force on Child Abuse program to recruit licensed clinicians to provide treatment to victims of sexual abuse. Through the award and a sub-grant to the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, now Rutgers University, the JJC sponsored two, free of charge, 40-hour training cycles in the northern and southern regions of the state. The training included lectures, homework, final examinations, and tours of JJC facilities, including the only community program for sexually abusive youth, the Pinelands Residential Community Home. Over 40 participants completed the course, which also provided continuing education units. The training was designed to enhance the skills of already licensed clinicians to deliver specialized services to sexually abusive youth.

The JJC has also recruited community providers to provide clinical services to JJC youth on an “as needed” basis, as well as funding for “wraparound” services. In addition, the JJC trained its Juvenile Parole and Transitional Services staff to provide community supervision and to collaborate with community providers and its secure care staff to work with sexually abusive youth in preparation for reentry.

The JJC is currently planning a statewide summit. The summit will bring together key public and private stakeholders throughout New Jersey and focus on the treatment, supervision, and obstacles to reentry for youth with sex offenses. Outcomes of the proposed summit will include the establishment of work plans, work groups, and resource materials for youth and service providers.

For more information, contact Sharon Lauchaire, Public Information Officer, New Jersey Juvenile Justice Commission.

Example: Texas Juvenile Justice Department’s Case Management Academy

The Texas Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD) recognizes the benefit of combining cognitive-behavioral interventions with motivational interviewing as a positive method to interact with youth. In addition, these interventions provide critical information for the department’s assessment tool, the Positive Achievement Change Tool. TJJD has trained all direct care staff, parole officers, and administrators in cognitive-behavioral interventions and motivational interviewing, and new hires must complete a Case Management Academy, in which they receive similar training. This greatly enhanced efforts for implementing effective interventions for youth in secure facilities.

For more information, contact Rebecca Thomas, Director of Integrated Programs and Services, Austin Office, Texas Juvenile Justice Department.

Conclusion

Incorporating the six programmatic functions into a single continuity of care plan that cuts across all reentry stages and is guided by an Overarching Case Management approach is not a matter of simply adopting a specific model or registry program. Rather, jurisdictions should develop programs and implementation processes tailored to their needs and that draw upon available evidence and best practices. Although there is no one right way to implement these critical elements, evidence-based programming that incorporates all six elements operating in tandem throughout the reentry continuum have proven to be most successful in achieving positive outcomes for youth.

This article showcases eight jurisdictions currently engaged in efforts to implement one or more of the six programmatic functions fundamental to reentry. These jurisdictions provide excellent illustrations of how each reentry function can be translated into practice.

David Altschuler, Ph.D., is Principal Research Scientist and Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the Johns Hopkins Institute for Health and Social Policy. The primary focus of his work is juvenile justice reform and youth crime. Dr. Altschuler also directed a national demonstration initiative on intensive juvenile aftercare for the U.S. Department of Justice, and serves as a consultant to numerous states, national organizations, and local groups.

Shay Bilchik, J.D., is Founder and Director of the Center for Juvenile Justice Reform at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. The center advances a balanced, multi-systems approach to reducing juvenile delinquency that promotes positive child and youth development. Previously, Mr. Bilchik was the President and CEO of the Child Welfare League of America and the Administrator of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

New Hampshire Continues Justice Reinvestment Effort to Improve Conditions for People Who Are High Utilizers of Criminal Justice and Behavioral Health Systems

Read More

New Hampshire Continues Justice Reinvestment Effort to Improve Conditions for People Who Are High Utilizers of Criminal Justice and Behavioral Health Systems

Read More

New Hampshire Commission Reviews Final Policy Recommendations to Reduce Reliance on Incarceration as Part of Justice Reinvestment Initiative

Read More

New Hampshire Commission Reviews Final Policy Recommendations to Reduce Reliance on Incarceration as Part of Justice Reinvestment Initiative

Read More

Three Things to Know About New Jersey’s Groundbreaking Community Response Legislation

Three Things to Know About New Jersey’s Groundbreaking Community Response Legislation

In response to growing calls for police reform in New Jersey, particularly…

Read More