As formal “mental health courts” (MHCs) enter their third decade in existence, policymakers are increasingly looking to distill the best of research and practice into state standards that foster high-quality programing and accountability for MHCs in their states. The National Center for State Courts (NCSC) and the Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center have created this resource to describe states’ approaches to conveying these MHC standards—a term used for the purposes of this overview to describe various types of governing documents—including guidelines, principles, recommendations, operating rules, funding requirements, and certification checklists, among others—that have been utilized across the nation. Much like standards for other courts that have been around for decades[i], standards for MHCs aim to provide performance measures that can help to ensure the highest levels of access, fairness, timeliness, accountability, and the use of evidence-based practices for criminal justice and behavioral health care providers. MHC governing documents vary from state to state, based on the entity overseeing problem-solving courts (e.g. Administrative Office of the Court, Judicial Governing Committee, or Governor’s Office), degrees of court unification, and the role of the entity with oversight (e.g. funding bodies, certifying bodies, oversight committees).

Policy priorities and state-led reform efforts calling for guidance and structure to problem-solving courts (or standards) have generally grown out of jurisdictions’ desires to:

- Provide assistance with planning and implementation of new problem-solving courts;

- Inform training efforts for key team members and other criminal justice collaborators;

- Establish a means of ensuring accountability and establish a sound basis for court self-regulation;

- Provide structure that ensures continuity for courts navigating transitions in judicial or administrative leadership;

- Demonstrate courts’ effectiveness at meeting their stated goals

- Provide courts with a framework for internal monitoring (e.g., performance measures); and/or

- Ensure that the courts adhere to a model based on research and evidence-based best practices.

Increasingly, states have turned to the creation of standards to provide a framework of best practices and provide minimum standards for all MHCs. Standards can also enable MHCs to responsibly increase the number of participants the court serves by providing a uniform set of empirically-based processes that are highly reliable and replicable, such as guidance on identifying appropriate target population to ensure the appropriate participants are being served and net-widening is avoided Furthermore, these standards help promote communication among MHC stakeholders by clearly establishing common expectations and providing guidance on best practices.

State Standards for Mental Health Courts: A National Perspective

Agencies that undertake the development of statewide MHC standards face two important challenges: 1) creating an approach that is appropriate within the context of that state’s governing structure for courts and problem-solving programs, and 2) determining the appropriate level of enforceability.

Statewide standards for MHCs range from providing guidance to MHCs in the form of recommendations or guidelines, to minimum operating standards and/or requirements to receive and sustain state funding, which often results in the creation of a certification process or set of MHC operating rules.

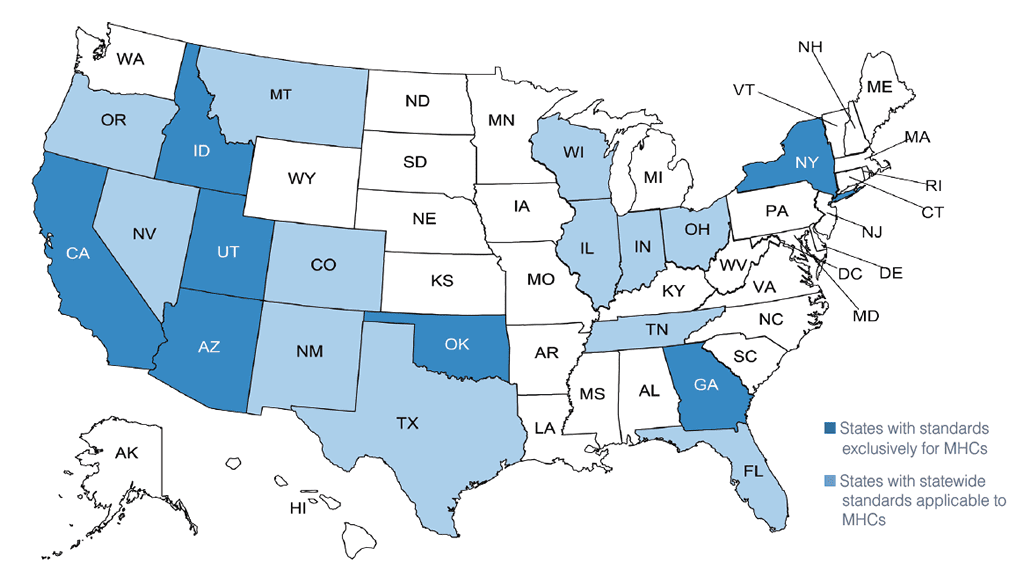

Of the 19 states with statewide standards applicable to MHCs, seven apply exclusively to MHCs. One state, Florida, provides recommendations for the mental health and criminal justice systems broadly, rather than addressing only the operations of MHCs. The other 11 states have issued governing documents that address multiple types of problem-solving courts (e.g., drug courts, veterans courts), but apply inclusively to MHCs.

The choice of language used to describe a state’s standards for its MHCs, and even what the governing document is called, is deliberate. There is a difference between, for example, a checklist that describes certification or funding requirements and a broad set of recommendations that may be much less prescriptive. The type of governing document and the vocabulary used within that document varies from state to state and reflects each state’s distinct priorities.

Statewide Mental Health Court Standards

In 2014, the NCSC conducted a review of states’ efforts to create governing rules and documents to serve as a reference for all problem-solving courts, including MHCs. In April 2016, NCSC reached out to state problem-solving court coordinators to update the list. The map above highlights 19 states with statewide MHC standards of some form. Several additional states are in the process of developing standards. To access individual state documents, go to ncsc.org/Services-and-Experts/Areas-of- expertise/Problem-solving-courts.aspx.

Cognitive Behavioral Programs

Cognitive behavioral programs help people who have committed crimes identify how their thinking patterns influence their feelings, which in turn influence their actions. These programs include structured social learning components where new skills, behaviors, and attitudes are consistently reinforced. Cognitive behavioral programs that target areas such as attitudes, values, and beliefs have a high likelihood of positively influencing future behavior, including a person’s choice of peers, whether he or she abuses substances, and his or her interactions with family. Most effective cognitive behavioral programs are action-oriented and often include components for people to practice skills through role-play with a trained instructor.

Monitoring the Quality of Program Delivery

Ohio, for instance, has set minimum requirements for certification across all specialized dockets and provides recommended practices that courts are encouraged but not required to follow. The Ohio Specialized Docket Standards establish a minimum level of uniform practices, but allows local specialized dockets to innovate and tailor programs to respond to local needs and resources.

Some states have established rules that require problem-solving courts to be certified and regularly demonstrate compliance. For example, the Indiana Judicial Center may take administrative action to ensure compliance with its rules, including suspension of court operations. Additionally, states have linked incentives, such as state funding, to achieving compliance. The standards in Georgia, for example, are tied to state funding and subject to review every three years.

While states with certification or funding-based requirements demand compliance, some courts also allow for an appeal or claim of hardship. This is the case in Idaho, for example, where the guidelines state that there must be substantial compliance to become or remain eligible for state funding, but courts can apply for a waiver. Often these types of exemptions are due to a lack of local resources.

Developing State Standards

The NCSC and CSG Justice Center have identified six key steps to follow when embarking on the development of statewide governing documents for MHCs.

Case Study: Arizona

Arizona convened a committee of key stakeholders to develop statewide standards for its MHCs to establish a means for the courts to monitor performance and conduct evaluations of the programs. Arizona’s standards are intended to guide courts seeking to establish a new MHC, enhance the effectiveness of existing MHCs, and navigate transitions in judicial leadership.

Recognizing the unique circumstances in each jurisdiction and the diversity among the operating MHC model, the committee developed eight standards representing fundamental components of MHCs,

but relied upon specific language to convey variations in degree of required compliance (e.g., “must” is mandatory, “may” allows for discretion, and “should” is recommended and encouraged).

- Understand the legal framework for MHCs in your state, as well as the role of different entities in funding and sustaining these programs.

- Consult existing research on evidence-based practices to guide standard development: While many resources exist that synthesize available research on mental health courts, planners should understand that the research base relevant to MHCs is significantly less prescriptive than the research for drug courts.

- Convene a group of stakeholders to ensure effective implementation of and secure support for the proposed governing documents: This should include not only those who will be responsible for promulgating the guidance and monitoring compliance, but also respected and thoughtful leaders representing a range of MHC programs. Care should be taken to ensure that a variety of program types are represented, including programs with different models, programs from jurisdictions with different levels of resources, and programs of different longevity and size.

- Determine whether “standards,” “guidelines,” “rules” or some combination of these approaches is appropriate based on the conditions in your state, such as the centralization of resources, unification (or not) of the court system, and the incentives for adherence.

- Decide on a strategy for monitoring compliance with the standards and responding to non-compliance, including identification of a monitoring agency; determine the minimum threshold for demonstrating compliance) and set a schedule for reporting and reviewing operating procedures and practices; identify incentives for compliance (e.g., serve as a mentor court, provide additional resources); and develop sanctioning or ameliorative policies (e.g., restrict funding, lose certification, receive targeted training or technical assistance).

- Create a mechanism built into the process to enable revisions as research evolves and as the guidance is tested on the ground with existing MHCs.

Additional Resources

The CSG Justice Center’s Developing a Mental Health Court: An Interdisciplinary Curriculum and the companion Handbook for Facilitators offer a wealth of resources and opportunities to connect with peers working in this area. The curriculum was funded by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance, and developed by the CSG Justice Center with input from advisors, including NCSC, from across the country.

In the fall of 2014, the CSG Justice Center hosted a web-based discussion among 15 state officials responsible for providing training and technical assistance to mental health courts in their states in order to foster an exchange of ideas, which NCSC participated in.

To learn more about or participate in this peer-learning group or to explore the curriculum, see learning.csgjusticecenter.org.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[i] See, Commission on Trial Court Performance Standards. 1997. Trial Court Performance Standards and Measurement System – Program Brief, Washington DC: Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance; National Center for State Courts. 2005. CourTools. Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts; Ostrom, Brian & Hanson, Roger (2010). “High Performance Court Framework: A Roadmap for Improving Court Management.” Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts; and Waters, Nicole L.; Cheesman II, Fred L.; Gibson, Sarah A.; Dazevedo, Ilonka. (2010). Mental Health Court Performance Measures: Implementation & User’s Guide. Williamsburg, VA: National Center for State Courts.

The CSG Justice Center Advisory Board establishes the policy and project priorities of the organization. The board features…

Read More Finding Solutions to Complex Criminal Justice Issues: Q&A with New CSG Justice Center Advisory Board Member Justice Briana Zamora

Finding Solutions to Complex Criminal Justice Issues: Q&A with New CSG Justice Center Advisory Board Member Justice Briana Zamora

The CSG Justice Center Advisory Board establishes the policy and project priorities…

Read More