Family Engagement in Juvenile Justice Systems: Building a Strategy and Shifting the Culture

To learn more about a new framework for family engagement and to help assess and improve your own policies and practice, View the Slideshow

The Problem

Youth in the juvenile justice system need their families to be centered and engaged in their experience in order to promote positive outcomes in their development and improve public safety.[1] While families provide the primary environment for youth as they grow up, system interventions usually do not include a youth’s family in a meaningful way.[2] Thus, family members cannot participate in or guide any skill building or emotional development or be prepared to adapt to changes in their child’s behavior, limiting the sustainability of these efforts.[3] Further, historically families have largely been studied only as a risk factor for delinquency,[4] but research shows that family engagement improves outcomes for youth by reducing mental health symptoms, spurring higher grade point averages, reducing behavioral infractions, and encouraging greater socioemotional skills.[5] However, jurisdictions across the country struggle to meaningfully prioritize family participation within the juvenile justice system, limiting the outcomes of interventions.[6]

This gap is not due to an unwillingness to engage with families on the part of system staff and leadership.[7] Rather, it is the result of not prioritizing strategic planning for family engagement and operating within a culture that is not inclusive of families’ needs. This system-focused, rather than family-centered, approach creates the following type of environment:

- System actors lack perspective on what families need to be able to participate in their child’s experience, hindering both parties’ ability to support positive outcomes.[8]

- Policies, procedures, and statutes do not take families into account or provide guidance on how families should be engaged.[9]

- Families receive minimal guidance and support on how to engage with the juvenile justice system, making it challenging to navigate the system, advocate for their child’s best interest, and play an active role in guiding and managing their child’s treatment and juvenile justice experiences.[10]

- Family engagement activities lack the money and time necessary to truly ensure they are a central part of case planning.[11]

- Parents and caregivers feel blamed and undervalued yet held responsible for their child’s behavior, creating negative emotions about their parenting abilities and confusion about their role.[12]

There is a host of evidence that a system-focused approach is not working for families of children in the juvenile justice system. According to a survey conducted by Justice for Families with more than 1,000 family members across 20 cities and 9 states, families report overwhelmingly negative and exclusionary experiences with the juvenile justice system:

- Ninety-one percent of family members said that courts should involve families more in decision-making about their child’s adjudication and disposition.

- Eighty-six percent of family members said they would like to be more involved in their child’s treatment while in a residential facility.

- Two out of three parents reported they must miss work and forfeit pay to support their child while involved in the juvenile justice system.

- More than one in three families shared that phone calls are too expensive, and these fees prohibit them from staying in touch and connected with their child.

- Only 18 percent of families feel that professionals in the juvenile justice system—judges, probation officers, public defenders, facility staff, and others—were “helpful” or “very helpful.”[13]

Despite clear evidence of the importance of including families to create and maximize positive outcomes for youth being served by the justice system, in most jurisdictions, families are not considered during strategic planning and are only included as an “add-on” to traditional system operations. The field has not moved forward when it comes to intentionally engaging and supporting the families it serves.[14] This has been especially evident during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, even as systems worked hard to reassess and transform their practices. Detention use decreased significantly, virtual probation and court hearings were introduced, and more, but system stakeholders did not prioritize the critical family support youth need to be successful. The fragile gains made by the “add-on” approaches eroded, and conversations with practitioners and experts in the field have indicated that most youth in the system endured residential placement and community supervision with even less family engagement than usual.

Building a Family Engagement Strategy and Shifting the Culture

The current strategies used to engage the families of youth involved in the juvenile justice system are ineffective at promoting deep and sustained engagement and perpetuate family disconnection instead of connection at a critical time in a youth’s life. System professionals and family stakeholders desire more active, fluid engagement with one another. This requires a shift not only in policy but also in the culture within juvenile justice agencies that is built around why and how families are engaged. System professionals have the power to make this shift a reality and can facilitate the promotion of strong family participation in the juvenile justice system.

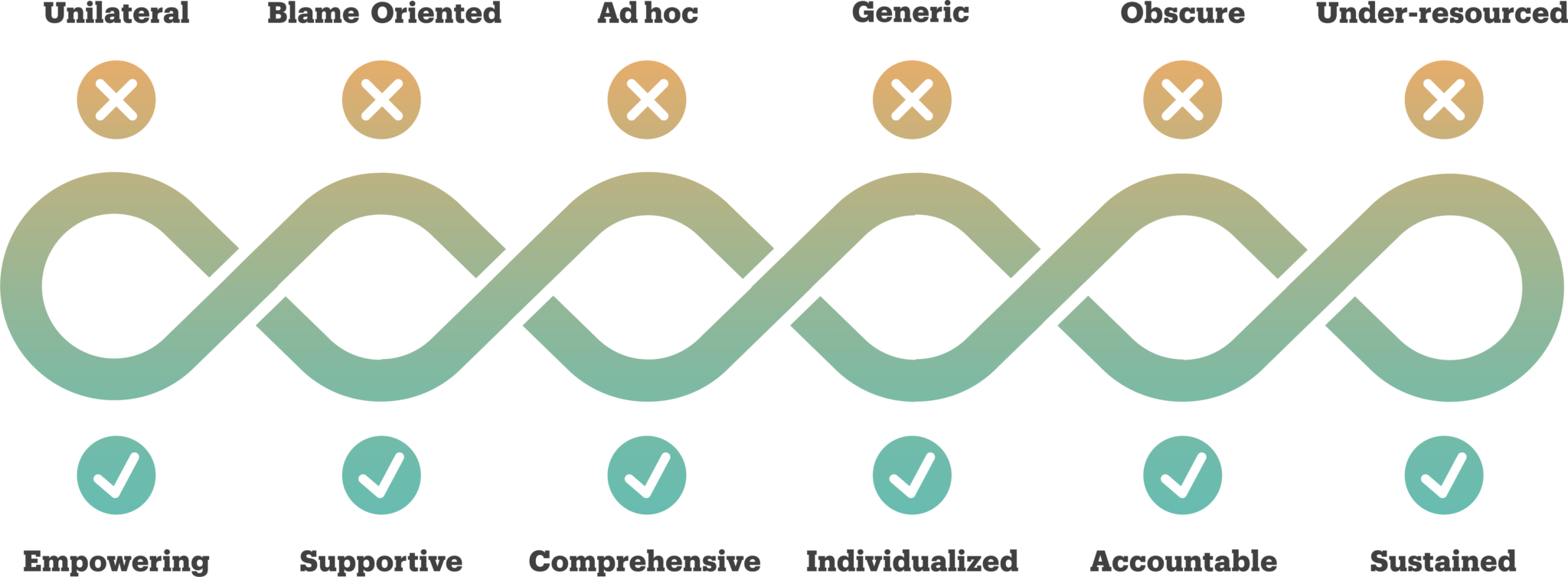

System-Centered Approach

- Unilateral: Removes authority from the family; system actors drive all decision-making, including if, how, when, and why families are engaged.

- Blame Oriented: Treats families as a tool or problem to overcome rather than a valued partner. Blames families for engagement challenges rather than considering how the system might be pushing them away.

- Ad hoc: Does not intentionally incorporate family engagement into all aspects of agency policy, practice, and funding. Instead, it is an “add-on” to processes and programming with no dedicated staff, resources, or accountability.

- Generic: The limited family engagement mechanisms that do exist are applied to all families in the same way and do not account for and respond to the differences in families or their circumstances.

- Obscure: No clear entryway and process for families to get information and navigate system processes, ask questions, understand their role, get the support they need to be engaged, obtain needed services, or provide feedback on their experience.

- Under-resourced: Rarely dedicates meaningful resources to supporting families, including training staff, facilitating court or program participation, or designating staff who focus on family engagement.

Family-Centered Approach

- Empowering: Enables families to shape and drive system decisions, including through family/team meetings, about court decisions, case plans, supervision terms, appointments and services, incentives and sanctions, and who counts as family.

- Supportive: Treats families as partners in the decision-making process, starting with what families want and need to help support their child’s success. Troubleshoots engagement challenges with families together and focuses less on blame than on mutual buy-in and support.

- Comprehensive: Develops an agencywide commitment to family engagement inseparable from the overall case planning, supervision, and service approach. This commitment is reflected in all aspects of policy and practice.

- Individualized: Meets the needs of individual families and ensures cultural alignment by allowing youth and families to define whom they consider family and using native languages and aligning engagement activities with cultural norms and practices.

- Accountable: Increases transparency and accountability for systems by sharing clear and frequent communication on system decisions and processes. Establishes performance measures on family engagement, evaluates progress—including through feedback from families—and shares the results with stakeholders and families.

- Sustained: Invests in family engagement by building organizational capacity through establishing positions focused on family engagement, collecting data, developing performance measures, and providing staff training and evaluations.

Working toward a Family-Centered Approach: Examples

Below are three examples of systems working to address family engagement in a comprehensive way that focuses on shifting system culture and treating families as experts and partners.

Shifting Court and Probation Culture

Juvenile Probation in Pierce County, Washington, engaged in a culture shift through a probation transformation initiative led by the Annie E. Casey Foundation in 2013. Through these efforts, the probation department intentionally examined how it was treating and involving families and became concerned about the narrative of families feeling demonized. To address this issue, the department started a Family Council to begin integrating families into policy and practice discussions. The department created a staff position dedicated to working with the Family Council and invested financial resources by providing the Council with a budget to support its development and goals. Through the course of establishing the Family Council and building trust across these new partners, the probation department worked to be transparent and accountable. Parents found allies in the court system and are now invited to the table consistently. As one member of the Family Council stated, “family voice is here.”

Engaging Family Voice to Structure Programming

Department of Youth Services (DYS) in Massachusetts intentionally reflected on its culture and wanted to include parents as part of the solution through a meaningful partnership. Critically, DYS directly confronted the culture by highlighting that parents and families are the experts who must care for their children once the juvenile justice system steps back. In addition to an intentional culture shift, DYS also comprehensively updated policy and clinical approaches. This included expanding the definition of family, extending times families could visit with their child, and utilizing virtual family therapy to engage families consistently even outside of visits. DYS also developed staff positions focused solely on family engagement that consistently work to iterate solutions and engage families across the state. Further, by working collaboratively with their Family Advisory Council, DYS identified needed supports for families. This included creating an opportunity for families to mentor and support one another through a Parent Café model, which brings parents together to share and learn, knowing they are not alone in their struggles with the juvenile justice system.[15]

Developing Family-Centered Programming

Montana Adult Department of Corrections (DOC) operates a program focused on incarcerated fathers to advance family engagement in the facility, which is supported by a grant from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. To further family engagement, the DOC developed peer mentorship programs for fathers in the facility as well as facilitating support between family members in the community. This program empowered parents and their families to take a leadership role in developing new strategies and thinking through what is necessary to build sustained family engagement. The program is structured such that it truly belongs to the participants and is continuously incorporating feedback from both the fathers in the facility as well as the families in the community to improve practices. As a result, the DOC identified tools and strategies to support meaningful and impactful family engagement that benefited individuals in the facility as well as families in the community through in-person visits and virtual engagement to maintain connection despite vast geographic challenges in Montana.

Steps toward a More Inclusive Approach

System professionals can take action to realize this strategic culture shift. Critically, the following actions are applicable to every level, from agency leadership to regional offices and individual decision-making:

- Establish a leadership team to guide the shift and identify, cultivate, and deputize organizational leaders to champion parents as experts and required partners in their work.

- Asses the current culture and approach across the key elements presented above and integrate solutions into all aspects of policy, practice, and programming.

- Develop formal family engagement and support mechanisms, such as a Parent Café, Family Advisory Council, or peer support staff in court to help guide families through the process, as well as intentional case management protocols that promote inclusion.

- Dedicate resources to promoting family engagement and support, such as creating staff roles dedicated to this work; developing budgets for Family Advisory Councils; providing childcare and transportation to courthouses, facilities, and services; implementing technology to facilitate family connection; and staffing courts and out-of-home placements in ways that promote opportunities for evening and weekend visits and hours of service.

- Create formal feedback loops by collecting and consistently reporting data that reflect family engagement, satisfaction, and recommendations through regular reporting; performance reviews of staff; and/or single events, like surveying parents in the court lobby.

- Create non-traditional partnerships, including with grassroots organizations, to promote the consideration of different approaches and a shift in culture, including contracting for a training or liaison staff position.

Juvenile justice systems are increasingly recognizing the importance of working with families and now, more than ever, courts, probation, and corrections agencies should consider a fundamental shift away from an ad hoc, system-centered approach to a culture and strategy that centers families in supervision and service policies and practices.

[1] Alyssa Mikytuck, Jennifer L. Woolard, and Michael Umpierre, “Improving Engagement, Empowerment, and Support in Juvenile Corrections through Research,” Translational Issues in Psychological Science 5, no. 2 (2019): 182–92.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Family Engagement in Juvenile Justice (Washington DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 2018), https://ojjdp.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh176/files/media/document/family-engagement-in-juvenile-justice.pdf.

[5] Mikytuck, Woolard, and Umpierre, “Improving Engagement, Empowerment, and Support,” 182–92.

[6] Family Engagement in Juvenile Justice.

[7] Brett Harris et al., Engage, Involve, Empower: Family Engagement in Juvenile Drug Treatment Courts (National Center for Juvenile and Family Court Judges and National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice, 2017).

[8] Leslie Paik, “Good Parents, Bad Parents: Rethinking Family Involvement in Juvenile Justice,” Theoretical Criminology 21, no. 3 (2016): 307–23.

[9] Family Engagement in Juvenile Justice.

[10] Lili Garfinkel, “Improving Family Involvement for Juvenile Offenders with Emotional/Behavioral Disorders and Related Disabilities,” Behavioral Disorders 36, no. 1 (2010): 52–60.

[11] Families Unlocking Futures: Solutions to the Crisis in Juvenile Justice (California: Justice for Families and Data Center Research for Justice, 2012).

[12] Paik, “Good Parents, Bad Parents,” 307–23.

[13] Families Unlocking Futures.

[14] Sarah Cusworth Walker et al., “A Research Framework for Understanding the Practical Impact of Family Involvement in the Juvenile Justice System: The Juvenile Justice Family Involvement Model,” American Journal of Community Psychology 56, no. 3–4 (2015): 408–21.

[15] Using Café Conversation to Build Protective Factors and Parent Leadership (Washington DC: Center for the Study of Social Policy, 2018).

Project Credits

Writing: Stephanie Shaw and Jacob Angus-Kleinman, CSG Justice Center

Advising: Josh Weber, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Leslie Griffin, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Aisha Jamil, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Web Development: eleventy marketing group