Adopting a Gender-Responsive Approach for Women in the Justice System: A Resource Guide

Adopting a Gender-Responsive Approach for Women in the Justice System: A Resource Guide

This guide to gender-responsive approaches was developed by The Council of State Governments Justice Center in partnership with the National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women. The guide can help program providers in behavioral health and criminal justice settings across the country develop gender-responsive programs. The guide focuses on six topics that are fundamental to carrying out effective programs for women in the justice system: Foundational Elements for Successful Gender-Responsive Programs, Key Facts about Women in the Criminal Justice System, Gender-Responsive Criminogenic Risk and Needs Assessment, Gender-Responsive Case Management, Gender-Responsive Programming, and Select Resources. Gender-Responsive Criminogenic Risk and Needs Assessment, Gender-Responsive Case Management, and Gender-Responsive Programming exist as independent fact sheets as well as in the guide. (Photo credit: Rebekah Zemansky / Shutterstock.com)

The Council of State Governments Justice Center prepared this resource with support from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) under grant number 2012-CZ-BX-K071 and 2019-MO-BX-K001. The opinions and findings in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice or the members of The Council of State Governments. The supporting federal agency reserves the right to reproduce, publish, translate, or otherwise use and authorize others to use all or any part of the copyrighted material in this publication.

About the CSG Justice Center: The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center is a national nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that combines the power of a membership association, representing state officials in all three branches of government, with policy and research expertise to develop strategies that increase public safety and strengthen communities. For more information about the CSG Justice Center, visit www.csgjusticecenter.org.

About the Center for Effective Public Policy’s National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women (NRCJIW): The National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women (NRCJIW) is a project of the Center for Effective Public Policy. The mission of the NRCJIW is to provide guidance and support to criminal justice professionals—and promote evidence-based, gender-responsive, and trauma-informed policies and practices—to reduce the number and improve the outcomes of women involved in the criminal justice system. For more information about the NRCJIW, visit http://cjinvolvedwomen.org/.

Introduction

While men still account for the majority of people in the criminal justice system, the proportion of women has been growing steadily over the past several decades. More than a million women are now either in prison or jail or on community supervision.1 Despite this, criminal justice policies, practices, and programs have historically been designed for men and applied to women without consideration of women’s distinct needs. While gender-neutral approaches—if evidence-based—can be effective in reducing recidivism for both men and women, research has shown that gender-responsive approaches result in far better outcomes for women.2

Gender-responsive and trauma-informed policies, practices, and programs recognize that women have distinct histories, pathways to offending, and experiences in the criminal justice system.3

These approaches address issues that may contribute to women’s involvement in the justice system, such as domestic violence, abuse, and victimization; family and relationships; trauma; and poverty, mental illnesses, and substance use disorders.

This guide to gender-responsive approaches was developed by The Council of State Governments Justice Center in partnership with the National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women. It was originally compiled for Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program grantees who are working to improve criminal justice and behavioral health outcomes for women in the criminal justice system. However, the guide can help program providers in behavioral health and criminal justice settings across the country develop gender-responsive programs.

The guide focuses on six topics that are fundamental to carrying out effective programs for women in the justice system:

- Foundational Elements for Successful Gender-Responsive Programs

- Key Facts about Women in the Criminal Justice System

- Gender-Responsive Criminogenic Risk and Needs Assessment

- Gender-Responsive Case Management

- Gender-Responsive Programming

- Select Resources

The guide highlights foundational elements for building gender-responsive programs and presents ongoing strategies to help improve responses to women in the criminal justice system. Select organizations, websites, and resources for continuing to advance your gender-responsive programming efforts are also provided. This guide can be used whole or in part, depending on which sections are most relevant to your needs. “Gender-Responsive Criminogenic Risk and Needs Assessment,” “Gender-Responsive Case Management,” and “Gender-Responsive Programming” exist as independent fact sheets as well as in this guide.

Foundational Elements for Successful Gender-Responsive Programming

Planning and implementing evidence-based programming with fidelity—including gender-responsive programming—can present an array of challenges. Among the many decisions, behavioral health and criminal justice program providers must make are how to manage referrals to the program, engage participants, tailor program dosage and intensity, respond to behaviors fairly and consistently, and collect and analyze data to measure performance. Efforts to ensure program sustainability (once grant funding ends, for example) can be even more difficult, as can obtaining full support from criminal justice and community stakeholders and producing desired outcomes over time. And most program providers will need to plan and implement such activities for multiple programs at a time. Considering these factors at the outset of planning can help providers implement programming more effectively and ensure that they are capable of yielding long-lasting positive effects. Below are best practices for planning and implementing any program, but especially gender-responsive ones.

Engage stakeholders.

You should engage and gain buy-in from people who have (or should have) a stake in your program’s success or who may be natural allies during program planning and implementation. This can be critical to growing and sustaining support for your program. As you work to adopt a gender-responsive approach, people who can bring important perspectives in these areas, such as women’s and victim services organizations, will be important to engage. Additional stakeholders include criminal justice decision-makers (e.g., judges, law enforcement leaders, prosecutors, defense attorneys, sheriff/jail administrators, and probation supervisors), community organizations (e.g., faith-based organizations, recovery centers, treatment providers, community-based advocates), state/local government officials, and funders.

Examples of how to engage stakeholders:

- Host a stakeholder meeting to launch the program.

- Once the program is up and running, invite stakeholders to observe it in action or to attend a program event (for example, a graduation).

- Conduct one-on-one or small group discussions to inform people about the program’s progress at important intervals and to solicit their input throughout implementation.

- Ask to be included on the agenda of meetings with partner groups or organizations to provide regular updates about the program.

- Pitch news articles about the program to local newsletters and newspapers.

- Conduct training events to increase stakeholder knowledge and engagement about the issues facing women in the criminal justice system.

- Consider whether the program may benefit from an advisory group. Ideally, this group would be composed of a diverse group of people who add value and can advocate for the program.

Conduct a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats (SWOT) analysis of the program.

This should be done at important intervals, such as the beginning of new activities or programs or before revamping policies, to note successful strategies and ongoing issues to address. A SWOT analysis begins with identifying the program’s strengths and opportunities for enhancement and expansion, including existing efforts to apply a gender-responsive approach. Second, it involves identifying the program’s weaknesses and any barriers or challenges in using a gender-responsive approach to accomplish identified goals. Once those analyses are completed, the team can identify strategies for building on the strengths and opportunities for addressing weaknesses and challenges. Next, create a work plan with specific details on implementing gender-responsive best practices based on the analysis that match your initiative’s needs.

Develop a criminal justice “system map.”4

Developing a flowchart of how women come into contact with and move through the criminal justice system and engage in behavioral health services is critical to understanding where interventions and supports can be most useful. Similar to mapping using the Sequential Intercept Model,5 communities can often use this process to identify the volume of women flowing through each criminal justice decision point and what resources, decisions, and gaps are present at each point. By design, mapping is a group endeavor that may take hours or days to complete depending on how detailed the map is. This is because the process brings together decision-makers and staff across organizations to articulate the decisions they make at various points in the system. Mapping can increase everyone’s awareness of how the entire system functions and how different parts of the system interact with one another. Most importantly, however, teams should determine where a program fits on the map to make sure it has the greatest impact. Exploring key gaps can help identify current and future opportunities to enhance gender-responsive services in the jurisdiction. The mapping group can also discuss whether additional action steps are needed to ensure that the new gender-responsive initiative/program is able to achieve its intended outcomes.

Conduct a Gender-Responsive Policy and Practice Assessment (GRPPA).6

Developed by the National Institute of Corrections and the Center for Gender and Justice, the GRPPA is an interactive instrument for evaluating current gender-responsive policies and practices. The GRPPA is intended for use by policymakers and practitioners to assess the strengths of and gaps in current resources for women in the criminal justice system. Conducting a GRPPA can help program providers gain a better understanding of how their current policies and practices affect women in the criminal justice system and inform strategies for enhancing or expanding a gender-responsive approach.

Build collaborative partnerships.

It is difficult, and perhaps impossible, to implement effective programs in isolation. This is especially true when working with women in the criminal justice system who often have myriad needs that must be addressed by multiple agencies if they are to be successful. By working collaboratively with partners, you can help ensure that multiple services are provided in a coordinated and efficient way. When building partnerships, you should consider how various agencies and organizations can help enhance and sustain service delivery to the women your program serves. Further, there may be opportunities through these collaborations to better coordinate gender-responsive services.

Tips for building and sustaining successful partnerships:

Consider the strengths each partner can bring to the collaboration and how those strengths can be enhanced.

Establish clear roles and responsibilities for each partner and conduct regular multidisciplinary team or case conferencing meetings at the direct service level to examine how the team is working together.

Identify existing resources from each partner that can be used to help address any gaps at various points in the system.

Provide cross-system training opportunities so that all staff in the partners’ organizations are knowledgeable and clear about program goals and objectives as well as gender-responsive and trauma-informed approaches.

Develop a communications strategy that tells your story and builds awareness about women in the criminal justice system.

A communications plan will help facilitate support for your program and lift up its profile in your community. The communications plan can include an approach to raise awareness about women in the criminal justice system by highlighting their distinct needs and addressing misconceptions about how they become involved in the system.

A communications plan should also promote the program’s benefits and successes. To best do this, teams should collect quantitative and qualitative data on the outcomes of the women participants from the very beginning. Quantitative data may include recidivism measures (e.g., rearrests, reconviction, reincarceration, revocations), length of time spent in custody, incidents in custody, behavioral health treatment connections and recovery supports, as well as education attainment, employment, and housing placement. Qualitative data can include the number of referrals to treatment and other support services, engagement in these services, participant feedback, and staff satisfaction surveys. Women in the program sharing their lived experiences can also be invaluable in presenting the impact of programming and often more compelling than providers telling their stories for them.

Data and information that has been collected can then be used as part of an engagement strategy with media, the community, and external stakeholders (such as elected officials) about the benefits and successes of the program. The data can also help determine what adjustments to the program and/or to the larger behavioral health and criminal justice systems may be needed.

Questions to consider when developing a communications plan:

Who are the key audiences you want to communicate with? Why? For each audience you identify:

- What are the most useful ways to reach them (i.e., social media, personal appeals, newspapers)?

- What do you want them to know?

- What is their perspective (for example, do they have a positive outlook on women in the criminal justice system)?

- Who from the program is best positioned to communicate with them?

Key Facts about Women in the Criminal Justice System

Contrary to common misconceptions, the proportion of women in the criminal justice system has increased dramatically over the past several decades.7 Women in the criminal justice system have markedly different experiences from those of men. Women follow unique pathways into the criminal justice system and can present patterns of criminogenic risk that point to different intervention needs.8 However, program providers, correctional personnel, community supervision agents, and others working with women often do not have a full understanding of some of these differences. This section provides some basic facts about women in the criminal justice system and highlights information that can be used to inform gender-responsive approaches and program planning.

Women are a significant and growing population in the criminal justice system.

Since 1980, the number of women in U.S. prisons has increased by more than 700 percent and outpaced men by more than 50 percent.9 And while arrests have dropped overall in recent years, the decrease is more pronounced for men (down 22.7 percent from 2005 to 2014) than it is for women (down 9.6 percent in the same period).10 In fact, more than 1.3 million women were arrested in the U.S. in 2014.11 And the number of women in local jails increased 44 percent between 2000 and 2013.12 Additionally, 1.2 million women were under some form of correctional control in 2013.13 A recent study that examined incarceration rates for women worldwide found that the 25 jurisdictions with the highest rates of incarcerated women were individual U.S. states.14 Transgender women, especially transgender women of color, are also incarcerated at higher rates than other groups. A 2011 survey found that approximately 21 percent of transgender women have been incarcerated in jail or prison at some point in their lives.15

Further, many of the policies and practices that were put in place in the past 30 years have directly affected the rise of women in the criminal justice system, such as state and national drug policies that mandated prison terms for even relatively low-level drug offenses, changes in law enforcement practices (particularly those targeting neighborhoods of color), and post-conviction barriers to reentry that distinctly affect women.16 Between 1986 and 1999, for example, the number of women incarcerated in state facilities for drug-related offenses alone increased by 888 percent (compared to an increase of 129 percent for non-drug offenses).17 These policies had an even greater impact when accounting for the intersections of gender, race, and ethnicity. While recently there has been a notable dip in the incarceration rate of Black women, in 2014 alone, the imprisonment rate for Black women was still more than twice the rate of imprisonment for White women. For Latina women, incarceration rates were 1.2 times the rate of White women in 2014.18

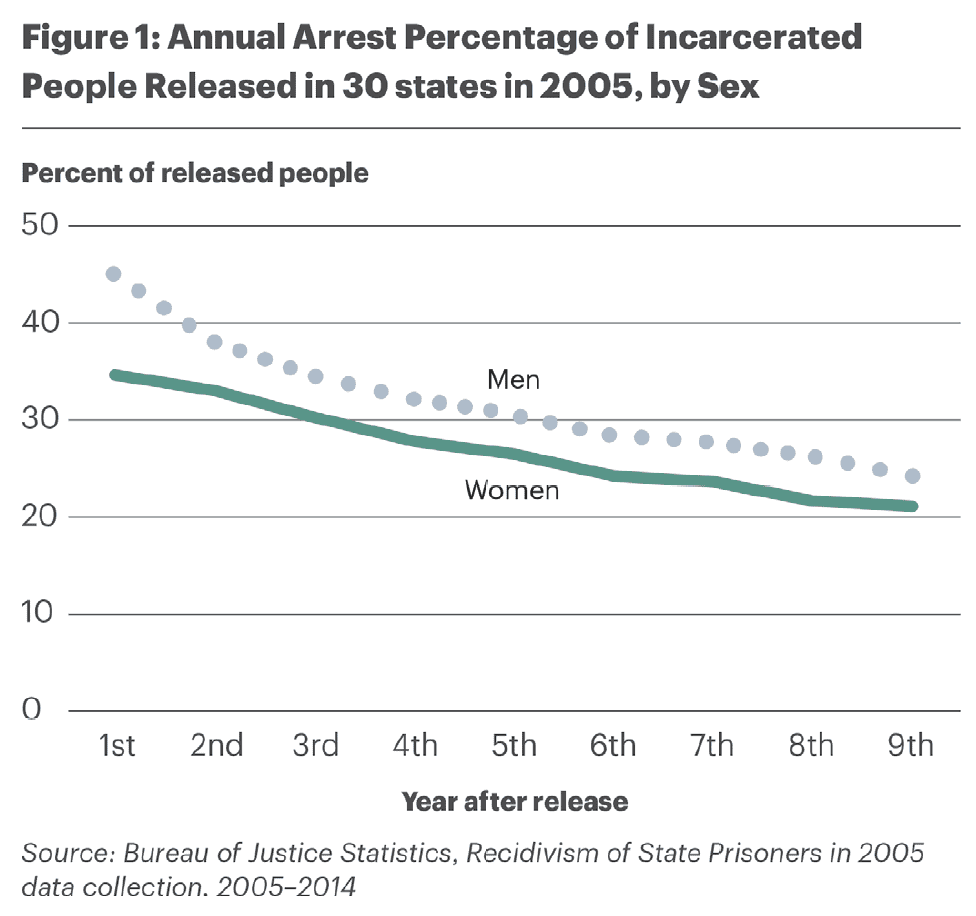

Women’s recidivism rates are similarly troubling compared to men’s. As of 2010, about one-quarter of women released from prison returned to custody within 6 months (i.e., were arrested for a new crime), one-third returned within a year, and two-thirds returned (68.1 percent) 5 years after release.19 Figure 1 shows recidivism rates of men and women released from prison in 30 states in 2005.

Women have different “pathways” to crime.20

Research conducted over the past two decades has identified some distinct drivers of criminal behavior among women and girls. While there is not one single, dominant pathway that leads women to enter the criminal justice system, particular types of experiences can trigger them to engage in behavior that results in an arrest. Some common factors that have emerged in research include experiences of abuse or trauma, mental illnesses and/or substance use disorders, poverty, marginalization, and unhealthy relationships.21

Childhood victimization drives some girls to run away from home and use illegal drugs as a means of coping with the trauma of physical and sexual abuse. Selling drugs, engaging in prostitution, and participating in burglary can then sometimes follow as a means of street survival.22

Women who experienced childhood victimization sometimes resort to using drugs to cope with the pain of that abuse as well as other stressors in their lives, such as intimate partner violence, sexual assault, or grief over the loss of custody of their children. Thus, there is a connection between prior or current victimization, mood and anxiety disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD]), and substance using behaviors (i.e., self-medicating).23

Poverty or economic reasons can motivate some women to sell drugs, engage in prostitution, or commit other crimes to support themselves and/or their children. They may also participate in these activities to support an addiction or a partner’s addiction.24

A smaller proportion of women appear to be primarily economically motivated and do not have a substance use disorder. Their arrests are instead related to the poor economic conditions they face.25

Women often get into and out of the criminal justice system in the context of unhealthy relationships (e.g., a male partner who encourages substance use or prostitution) 26or familial obligations. Research on female psychological development illuminates how women’s identity, self-worth, and sense of empowerment are defined by and through their relationships with others.27 In contrast, men’s major developmental issues are achieving autonomy and independence.

Women come to and experience the criminal justice system differently.

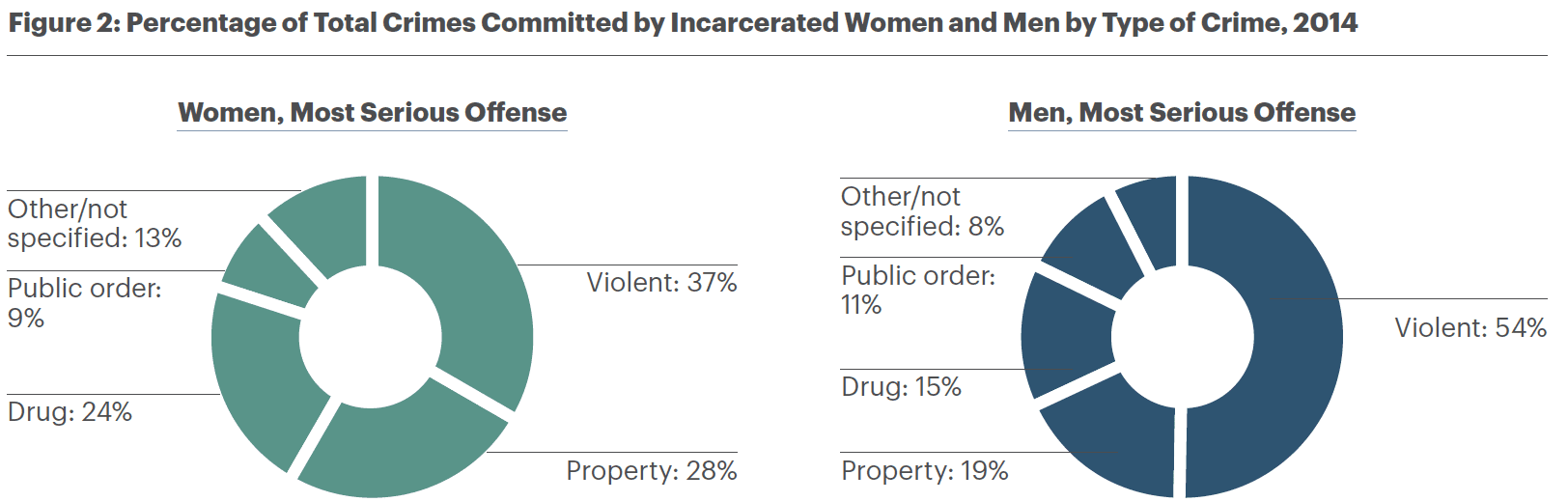

Most women not only encounter the criminal justice system for different reasons than men, but they also experience the system differently, have different risk factors for reoffending, and have varied life circumstances. For example, women are more likely than men to commit drug offenses, such as possession and trafficking28 (see Figure 229), and women under correctional supervision are more likely than men to report having experienced physical and sexual abuse as children and adults.30

Table 1 summarizes some of the differences experienced by women and men in the criminal justice system.

Table 1: Comparison of Women and Men in the Criminal Justice System At a Glance

| WOMEN | MEN | |

| Offending Patterns | Women primarily commit property (28 percent) and drug offenses (24 percent).31

About one-third commit violent offenses,32 which are often targeted toward a close relative or intimate partner.33 Women are less likely than men to have been convicted of a violent crime.34 Women, on the whole, are at a lower risk of serious or violent institutional misconduct35 and are also less likely to re-offend in the community than men.36 |

More than half (54 percent) of men in prison have been convicted of a violent offense.37

Less than half of offenses committed by men in prison are property (19 percent) and drug offenses (15 percent).38 |

| Family Roles/Relationships | Women are more likely to have served as the primary caretakers of children prior to entering prison39 and have plans to return to that role upon release.40

For many women, their children are often the primary factor motivating them to reduce recidivism.41 Women in the criminal justice system are often concerned with their children’s welfare and the potential loss of legal custody. For instance, the Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997 requires termination of parental rights when a child has been in foster care for 15 or more of the past 22 months. Given that average prison terms for women are 18 to 20 months, this time period has particularly serious consequences for incarcerated mothers.42 Sense of self-worth is often built from their connections with others.43 |

Men are less likely to serve as the primary caretaker of children.44

Psychological theories describe men’s path to maturity as becoming self-sufficient and autonomous45 |

| Mental Illnesses | 66 percent of women in state prisons report exhibiting mental health concerns.46

Depression; anxiety disorders, including PTSD; and eating disorders are more prevalent.47 About one in three women in the criminal justice system meet criteria for current PTSD, with one in two meeting criteria for lifetime PTSD.48 Women in prison are twice as likely as men to take prescription medications for mental health concerns and receive therapy for their illness.49 A 2011–2012 national study showed that a larger percentage of women in prison (20 percent) or jail (32 percent) than men met the threshold for serious psychological distress in the 30 days prior to the study.50 There is some evidence that incarcerated women with mental illnesses may have higher infraction rates than incarcerated women without mental illnesses.51 |

55 percent of men in state prisons report exhibiting mental health concerns.52

Antisocial personality disorders are more prevalent.53 A 2011–2012 national study showed that 14 percent of men in prison and 26 percent of men in jail met the threshold for serious psychological distress in the 30 days prior to the study.54 |

| Substance Use Disorders | 69 percent of women in state prisons met the DSM-IV drug dependence or abuse criteria.55.

72 percent of women in jail met the DSM-IV drug dependence or abuse criteria.56 From 2007 to 2009, more women in prison (47 percent) or jail (60 percent) reported using substances in the month before their current offense than men in prison. (38 percent) or jail (54 percent).57 In a multi-site study of women in jails, 82 percent of the sample met lifetime criteria for drug or alcohol abuse or dependence.58 Women are twice as likely as men to suffer from co-occurring mental illnesses and substance use disorders.59 |

57 percent of men in state prisons met the DSM-IV drug dependence or abuse criteria.60

62 percent of men in jail met the DSM-IV drug dependence or abuse criteria61 From 2007 to 2009, 38 percent of men in prison and 54 percent of men in jail (60 percent) reported using substances in the month before their current offense.62 |

| Economic Marginalization | Despite lower earning potential on average, women often need to stretch their income farther to support any children they are raising.63

A greater percentage of women (37 percent) than men (28 percent) report incomes of less than $600 per month prior to their arrest. Research has found that 60 percent of women in jails were not employed full time before being arrested,64 while almost 30 percent said their primary source of income was public assistance.65 |

Men are more likely to be employed full time (60 percent of men vs. 40 percent of women).66 |

| Victimization and Trauma | A number of studies have found that about half of women in the criminal justice system report experiencing some kind of physical or sexual abuse in their lifetime, with some studies noting rates of trauma histories as high as 98 percent.67

Most common experiences include child and adult sexual violence and intimate partner violence.68 While the risk of abuse for men drops after childhood, the risk of abuse for women continues throughout their adolescent and adult lives.69 Some women have also reported that victimization continues while they are incarcerated, either at the hands of staff or other incarcerated women.70 |

Most common past traumas include witnessing someone being killed or seriously injured and being physically assaulted.71 |

Gender-Responsive Criminogenic Risk and Needs Assessment

The Problem

Criminogenic risk and needs assessments help guide decision-making at various points across the criminal justice continuum by estimating a person’s likelihood of recidivism. Some of these assessment instruments also identify individualized risk/need profiles, which assist in determining appropriate programs, interventions, and supervision levels to mitigate that risk. Most of these tools are designed to be gender-neutral and do not provide as much additional information about women’s criminogenic risks and needs as gender-specific instruments do. Some risk factors critical to women (e.g., relationship conflict, housing safety, and mental health) are often absent in gender-neutral tools altogether.72 And despite the fact that strengths and protective factors, such as self-efficacy, family support, and education, have been shown to significantly impact women’s recidivism outcomes, gender-neutral tools do not examine or weigh these items differently for men and women.73 As a result, research suggests that gender-neutral tools are less valid for women than for men and may overclassify women into higher-risk categories than their behaviors warrant.74

Applying a Gender-Responsive Approach

Gender-responsive criminogenic risk and needs assessment instruments incorporate the same principles as traditional gender-neutral assessments but also examine gender-responsive factors for women. These assessments weigh risk factors differently and include risk factors that are predictive for women only, such as depression, anxiety, and unhealthy relationships.75

Table 2 provides information about gender-responsive risk and needs assessment tools and additional tools that are useful when working with women in the criminal justice system. The results of these assessments will be critical to tailor programming to meet the distinct needs of women, make pretrial risk decisions, and determine the intensity level of community-based supervision.

Table 2: Gender-Responsive Tools

| TOOL NAME | DESCRIPTION |

Criminogenic Risk and Needs Assessment—Pretrial |

|

| Gender Informed Needs Assessment (GINA) 76 |

The GINA is an assessment designed to be used with women in the pretrial stage. 77 |

Criminogenic Risk and Needs Assessments—Pre- or Post-Sentencing |

|

| Northpointe Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions (COMPAS) for Women | The COMPAS assessment includes a gender-responsive scale that can be used when assessing women.78 |

| Service Planning Instrument for Women (SPIn-W) | The SPIn-W contains about 100 items that assess risk, needs, and protective factors that are relevant for increasing responsiveness in casework with women in the criminal justice system. The full assessment includes 11 domains.79 |

| Women’s Risk and Needs Assessments (WRNA), both the stand-alone and trailer instruments80 | The National Institute of Corrections, in cooperation with the University of Cincinnati, developed the WRNA. The assessment includes a full instrument of about 80 items that assess both gender-neutral and gender-responsive factors and provides separate forms for probation, prison, and pre-release. The WRNA-Trailer is designed to supplement existing risk and needs assessments (e.g., LSI-R, COMPAS). New versions of the WRNA and WRNA-T were released in 2014.81 |

Trauma-Focused Screening Instruments |

|

| Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) | The ACEs questionnaire is a 10-item self-administered questionnaire that measures the impact of childhood experiences on adult health and negative consequences. The higher the ACE score the more likely negative impacts are in adulthood.82 |

| Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5)83 | “LEC-5 is a self-report measure designed to screen for potentially traumatic events in a respondent’s lifetime. The LEC-5 assesses exposure to 16 events known to potentially result in PTSD or distress and includes one additional item assessing any other extraordinarily stressful event not captured in the first 16 items.”84 |

| Life Stressor Checklist-Revised (LSC-R)85 | The LSC-R is a self-report measure that assesses stressful life events. The LSC-R contains 30 items that ask about exposure to traumatic events, including natural disasters; accidents; physical/sexual abuse; and other stressful life events, such as divorce, foster care, and financial difficulties. Some events, like sexual abuse, are queried for occurrence in both childhood and adulthood. The instrument also includes an item specific to women (occurrence of abortion).86 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5)87 | “The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report assessment that assesses the 20 DSM-5 symptoms of PTSD. The PCL-5 is a screening tool for PTSD, helps professionals make a PTSD diagnosis and helps to monitor symptom change during and after treatment.”88 |

| Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire (SLESQ) | The SLESQ is a 13-item self-report measure that assesses lifetime exposure to traumatic events.89 |

Gender-Responsive Case Management

The Problem

Risk assessment, classification, and programming processes in the criminal justice system were developed with the needs of men in mind. Similarly, case management approaches—which seek to connect people to needed social, medical, behavioral health, housing, and other services—have not fully taken into account the distinct needs of women.90 As a result, gender-responsive case management models have been created to better respond to women’s complex risks and needs and to connect them with resources and treatment to support successful reentry and recovery in the community.

Applying a Gender-Responsive Approach

The Women Offender Case Management Model (WOCMM), now known as Collaborative Case Work with Women (CCW-W),91 is a case management model designed specifically for use with women in the criminal justice system. CCW-W uses gender-informed, evidence-based practices to support women’s recovery and success in the community while minimizing risk of further involvement in the criminal justice system. It was developed by the National Institute of Corrections and Orbis Partners to provide uninterrupted, coordinated services that can begin at sentencing and continue through community reentry and supervision. It is facilitated by a case manager who meets with a multidisciplinary team that can include medical personnel, treatment specialists, institutional staff, parole/probation officers, community providers, family members, mentors, and the woman herself.

The model is based on nine core principles:

- Provide comprehensive case management that addresses the complex and multiple needs of women in the criminal justice system.

- Recognize that all women have strengths that can be mobilized.

- Ensure that women are collaboratively involved to establish desired outcomes.

- Promote services that are unlimited in duration.

- Match services in accordance with risk level and need.

- Build links with the community.

- Establish a multidisciplinary “case management team.”

- Monitor progress and evaluate outcomes.

- Implement procedures to ensure program integrity.

Collaborative comprehensive case plans (CC case plans)92 can also be used to assist case planners and others with better integrating behavioral health and criminogenic risk and needs information into case plans that actively engage women in the criminal justice system. Like the CCW-W model, CC case plans involve collaboration between criminal justice, behavioral health, and social service systems to achieve more successful outcomes with women. They also specifically include gender considerations as one of the 10 priority areas of focus, because women often have different behavioral health needs and responsivity factors than men.

In Practice: Connecticut implemented the CCW-W with women in the Bridgeport, Hartford, New Britain, and New Haven probation sites and is seeing promising results. In one outcome evaluation of 174 women being supervised by the State of Connecticut Judicial Branch/Court Support Services Division, one-year follow-up data revealed that CCW-W participants had a significantly lower rate of new arrests in comparison to members of the matched control group (31.6 percent vs. 42.5 percent). The rate of any new arrests for high-risk CCW-W participants was also 36.1 percent compared to 49.5 percent for high-risk matched control group members.*

*Orbis Partners, Inc., Women Offender Case Management Model: Outcome Evaluation (Ottawa, Ontario: Orbis, Partners, Inc., 2010), https://cjinvolvedwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Women-Offender-Case-Management-Model.pdf.

Gender-Responsive Programming

The Problem

Existing gender-neutral correctional and community programming has historically been developed for men and as such has not taken into account the unique pathways of women into the criminal justice system. Women also have distinct criminogenic risks and behavioral health needs that must be addressed to support successful reentry, recovery, and recidivism reduction.

Applying a Gender-Responsive Approach

Gender-responsive programs seek to meet the specific needs and challenges of women in the criminal justice system. Program content recognizes the unique pathways that often lead women into contact with the criminal justice system. Interventions are also tailored to meet women’s criminogenic risks and needs, including parenting stress and mental health issues. In addition, applying a gender-responsive approach to programming recognizes women’s high rates of past and recent trauma (which may interplay with other behavioral health needs) and incorporates a trauma-informed approach and/or trauma treatment into programming as needed.93

Table 3 highlights programs that have been found to be effective when working with women in the criminal justice system. This table can be used to explore evidence-based programming options for women both pre- and post-release (or to enhance existing intervention protocols).

Table 3: Evidence-Based and Gender-Responsive Programming for Women in the Justice System: Evaluation Findings94

| PROGRAMMING | DESCRIPTION | EVALUATIONS |

A Woman’s Addiction Workbook: Your Guide to In-depth Healing95 |

This is a self-help workbook for women with substance use disorders and other addictions. The workbook includes material on dual diagnosis, trauma, and violence. | Results of a pilot outcome study indicated significant decreases in drug use (verified by urinalysis) and impulsive-addictive behavior along with global improvement and enhanced knowledge of the treatment concepts.96 |

Beyond Trauma: A Healing Journey for Women97 |

The Beyond Trauma program incorporates the insights of neuroscience with the latest understanding of trauma and PTSD. The materials are designed for trauma treatment, although the connection between trauma and addiction in women’s lives is a primary theme throughout. The program is based on the principles of relational therapy; it uses cognitive-behavioral techniques, mindfulness, expressive arts, and body-oriented exercises. | Studies on the program’s use in women’s prisons indicate the importance of addressing both trauma and substance use disorders in women’s recovery.98 Positive changes were found in specific domains of the Texas Christian University (TCU) Criminal Thinking, TCU Psychological Adjustment, and TCU Social Functioning scales for women who completed a combined Helping Women Recover/Beyond Trauma program at an Oklahoma women’s prison.99 Additional studies show that women who participate in Beyond Trauma demonstrate a decrease in depression, improvement during parole, increased participation in voluntary aftercare treatment services, decreased likelihood of being incarcerated at 6-month follow-up, and reported a reduction in PTSD.100 |

Beyond Violence: A Prevention Program for Criminal Justice-Involved Women101 |

Beyond Violence (BV) utilizes a multi-level approach and a variety of evidence-based therapeutic strategies (i.e., psychoeducation, role-playing, mindfulness activities, cognitive-behavioral restructuring, and grounding skills for trauma triggers) to assist women in understanding trauma, the multiple aspects of anger, and emotional regulation. | BV’s use with incarcerated women shows significant reductions in PTSD, anxiety, anger, aggression, and symptoms of serious mental illness.102 Preliminary results from a pilot BV program in one correctional facility in Michigan showed that during the first year on parole, BV participants were less likely to recidivate (33 percent of BV participants vs. 40 percent of non-participants); were less likely to test positive for drugs (58 percent vs. 80 percent), and produced fewer positive drug screens (average number of positive drug tests per person was 1.88 for those in the outpatient BV group vs. 3.6 positive tests for those in the “treatment as usual” outpatient substance use group of women with violent offenses). BV participants also had better treatment adherence outcomes.103 |

Boston Consortium Model (BCM): Trauma-informed Substance Abuse Treatment for Women |

The BCM program “provides a fully integrated set of substance use treatment and trauma-informed mental health services to low-income, minority women with co-occurring alcohol/drug addictions, mental disorders, and trauma histories.”104. | A quasi-experimental study found decreased substance use and related problem severity; fewer mental health symptoms, including decreased PTSD from the 6- to 12-month follow-up, and decreased risky sexual behavior from baseline to the 6-month follow-up for women in the BCM group compared to women in usual substance use disorder treatment.105 |

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT)106 |

DBT is a cognitive-behavioral approach involving skills training, motivational enhancement, and coping skills. | DBT has been tested in many settings and has been found to increase intermediate outcomes, such as reductions in drug use, suicide attempts, and eating disorder measures, and improvements in mental health symptoms.107 One study of girls in the juvenile justice system found reductions in behavioral problems.108 |

Engaging Women in Trauma-Informed Peer Support109 |

This guide was created by the National Center on Trauma-Informed Care and is designed as a resource for peer supporters in behavioral health or other settings who want to learn how to integrate trauma-informed principles into their relationships with the women they support or into the peer support groups of which they are members. The guide provides information, tools, and resources needed to engage in culturally responsive, trauma-informed peer support relationships with women. | Research demonstrates that peer support contradicts many of the negative messages received through traumatic experiences and service systems about victims’ identity and capabilities.110 |

Helping Women Recover: A Program for Treating Addiction111. |

Helping Women Recover addresses substance use disorders by integrating the four theories of women’s offending and treatment: pathways, addiction, trauma, and relational theories. | Evaluation results for the combined Helping Women Recover/Beyond Trauma program at an Oklahoma women’s prison are the same as above. |

Integrated Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (ICBT) |

ICBT is non-exposure-based, manual-guided individual or group therapy. ICBT consists of three learning and skill components designed to improve PTSD symptoms and substance use disorders: (1) patient education about PTSD and its relation to substance use and treatment, (2) mindful relaxation, and (3) cognitive restructuring/flexible thinking. | Trials of ICBT have resulted in significantly greater reductions in both PTSD and substance use disorders.112 |

Moving On113 |

Moving On’s goals are to provide women with opportunities to mobilize and enhance existing strengths and access personal and community resources. It also incorporates cognitive behavioral techniques with motivational interviewing and relational theory.114 | An evaluation of its use with women on probation in Iowa confirmed its effectiveness in reducing recidivism.115 |

Risking Connection |

Risking Connection is a comprehensive, manualized, 20-hour, 5-module curriculum program that seeks to further implement trauma-informed service systems; enhance trauma-specific service delivery to trauma survivors; and improve all staff interactions with consumers, including the most difficult to treat, suicidal, and self-injuring ones. Risking Connection has been adapted for use in multiple settings and fields including correctional, substance use, and developmental disabilities. | Risking Connection is based on empirically and theoretically validated concepts, such as the role of the therapeutic relationship, psychoeducation, empowerment, and the effects of the work on the worker.116 |

Sanctuary Model |

This program is a full-system approach that targets the entire organization with the intention of improving client care and outcomes. The focus is to create a trauma-informed and trauma-sensitive environment in which specific trauma-focused interventions can be effectively implemented. | Analyses demonstrate that this model is effective in reducing symptoms from admission to discharge and that treatment gains were maintained one year after discharge.117 Use of this model in inpatient psychiatric settings resulted in decreases in the following areas: use of locked seclusion, use of emergent and forced medication injections, and overall staff and patient injuries.118 |

Seeking Safety119 |

Seeking Safety treats co-existing trauma, PTSD, and substance use disorders. It draws from the research on cognitive behavioral treatment of substance use disorders, post-traumatic stress treatment, and education. | Evaluations indicate improvements in social adjustment, psychiatric symptoms, problem-solving, substance use, and depression.120 A study of peer-led Seeking Safety found significant positive outcomes in trauma-related problems, psychopathology, functioning, self-compassion, and coping skills.121 In a recent randomized controlled study, Seeking Safety participants had significantly fewer trauma symptoms and less depression than the control group.122 Evaluations on the program’s use with women in the criminal justice system also show promising results.123 |

The Addictions and Trauma Recovery Integration Model (ATRIUM)124 |

ATRIUM provides a blend of psychoeducation, process, and expressive activities, all of which are structured to address key issues linked to the experience of both trauma and addiction. This recovery model may be used in conjunction with 12-step or other substance use disorder treatment programs, as a supplement to trauma-focused psychotherapy, or as an independent model for healing. | ATRIUM was used in one of the nine study sites of SAMHSA’s Women, Co-Occurring Disorders and Violence Study. Across all sites, trauma-specific models achieved more favorable outcomes than control sites that did not use trauma-specific models.125 |

Trauma Addictions Mental Health and Recovery (TAMAR)126 |

TAMAR is a structured, manualized 10-week intervention combining psychoeducational approaches with expressive therapies. It is designed for women and men with histories of trauma in residential systems. Groups are run inside detention centers, state psychiatric hospitals, and in the community. | Initial research indicates that women participants in TAMAR have significantly lower recidivism rates back to detention centers, improved self-esteem and coping skills, and reduced incidence of contracting HIV and other STIs.127 |

Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy (TARGET)128 |

TARGET is an educational and therapeutic approach for the prevention and treatment of complex PTSD. This model provides practical skills that can be used by trauma survivors and family members to de-escalate and regulate extreme emotions, manage intrusive trauma memories experienced in daily life, and restore the capacity for information processing and memory.129 | In field trials with groups of low-income women in residential, intensive outpatient, or criminal justice diversion treatment for substance use disorders or domestic violence (80 percent of which were Black or Latina), 50 percent reported symptoms sufficient to warrant a diagnosis of PTSD prior to TARGET. Following 10 TARGET group sessions, only 20 percent continued to warrant a PTSD diagnosis.130 |

Trauma Recovery and Empowerment Model (TREM) |

TREM is intended for trauma survivors, particularly those with exposure to physical or sexual violence. This model is gender specific: TREM for women and MTREM for men. This model has been implemented in mental health, substance use, co-occurring disorder, and criminal justice settings. | TREM groups have shown a very high rate of retention, even among women with multiple vulnerabilities and few supports. Pilot studies have indicated a high level of participant satisfaction with the group, with over 90 percent finding it helpful on a number of trauma-related dimensions, including recovery skill development. Preliminary studies of TREM have found improvement in overall functioning; mental health symptoms (including anxiety and depression); and trauma recovery skills (e.g., self-soothing, emotional modulation, and self-protection). In addition, these evaluations found decreased high-risk behaviors and reduced use of intensive services, such as emergency room visits and hospitalizations. Quasi-experimental study results showed advantages for using TREM over services as usual in both PTSD symptoms and drug and alcohol use.131 |

Treating Women with Substance Use Disorders: The Women’s Recovery Group Manual132 |

This manual emphasizes self-care and developing skills for relapse prevention and recovery. Grounded in cognitive behavioral therapy, this manual is designed for a broad population of women with substance use disorders, regardless of their specific substance of use, age, or co-occurring disorders. | Evaluations show that the Women’s Recovery Group Manual is effective, as demonstrated by reduction of substance use during and after treatment and increased group affiliation/bonding.133 |

Using Matrix with Women Clients: A Supplement to the Matrix Intensive Outpatient Treatment for People with Stimulant Use Disorders |

This guide enhances the counselor’s treatment manual in the Matrix series, addressing the specific needs of women who misuse stimulants. It contains materials to help counselors conduct intensive outpatient treatment sessions on relationships, trauma, body image, and family roles. | Studies have demonstrated that participants treated using the Matrix Model show statistically significant reductions in drug and alcohol use, improvements in psychological indicators, and reduced risky sexual behaviors. This supplement for women participants was developed in response to the unique needs and concerns of women in stimulant dependent treatment.134 |

Selected Resources

The following selected organizations and other resources are a few of the many tools currently available to professionals working with women in the criminal justice system.

Organizations

National Center for Transgender Equality

National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls

National Institute of Corrections

National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women

Resources

Ending Abuse of Transgender Prisoners: A Guide to Winning Policy Change in Jails and Prisons

LGBTQ Criminal Justice Reform: Real Steps LGBTQ Advocates Can Take to Reduce Incarceration

National Institute of Corrections’ Justice Involved Women Self-Guided E-learning (5 modules)

Ten Truths that Matter when Working with Justice Involved Women

The Gender Divide: Tracking Women’s State Prison Growth

The World Health Organization (WHO) Book on Prison Health (2014)

FY2017 Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program Learning Community Webinar Series on Gender-Responsive Services for Women in the Criminal Justice System:

Getting Smart About Gender-Responsive Services for Women with Justice Involvement

How to Engage Women During Screening and Assessment and Case Management Practices

Troubleshooting Around Implementation of Gender-Responsive Principles

Addressing Motherhood Through Gender-Responsive Programming

FY2018 Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program Learning Community Webinar on Gender-Responsive Services for Women in the Criminal Justice System:

FY2019 Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program Learning Community Webinar Series on Gender-Responsive Services for Women in the Criminal Justice System:

The Status of Gender and Trauma Informed Practices in Your System

Responding to Women’s Rule Breaking Behaviors

Women and Contact with Law Enforcement in the Community: A Closer Look

Achieving Successful Outcomes with Women Involved in Court Processes

Footnotes

1The Sentencing Project, Incarcerated Women and Girls (Washington, DC: The Sentencing Project, 2020), https://www.sentencingproject.org/publications/incarcerated-women-and-girls/#:~:text=Though%20many%20more%20men%20are,of%20the%20criminal%20justice%20system.

2Kelley Blanchette, Renee Gobeil, and Lynn Stewart, “A Meta-Analytic Review of Correctional Interventions for Women Offenders: Gender-Neutral Versus Gender-Informed Approaches,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 43, no. 3 (2016): 301–322.

3Barbara Bloom, Barbara Owen, and Stephanie Covington, Gender-Responsive Strategies: Research, Practice, and Guiding Principles for Women Offenders (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, 2003), https://info.nicic.gov/nicrp/system/files/018017.pdf.

4For further discussion and step-by-step instructions for developing a criminal justice system map, see “3A: Developing a System Map—Navigating the Road Map,” U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, accessed April 16, 2020, http://starterkit.ebdmoneless.org/starter-kit/3a-developing-a-system-map/.

5The Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) guides community and system-wide responses to people with mental illnesses and substance use disorders in the criminal justice system. SIM focuses on six discrete points of potential intervention (also known as intercepts) in the criminal justice system at which a person who has behavioral health needs might be screened, assessed, and connected to treatment. These six points are (0) community services, (1) law enforcement, (2) initial detention/initial court hearings, (3) jails/courts, (4) reentry, and (5) community corrections. See Policy Research Associates, The Sequential Intercept Model: Advancing Community-Based Solutions for Justice-Involved People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders (New York: Policy Research Associates, 2018), https://www.prainc.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/PRA-SIM-Letter-Paper-2018.pdf.

6For more information about the GRPPA, see “Gender-Responsive Policy and Practice Assessment (GRPPA): What is the GRPPA?,” U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, accessed April 15, 2020, https://nicic.gov/gender-responsive-policy-practice-assessment.

7The Sentencing Project, Fact Sheet: Incarcerated Women and Girls (Washington, DC: The Sentencing Project, 2015), http://www.sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/Incarcerated-Women-and-Girls.pdf.

8National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women, Ten Truths that Matter When Working with Justice-Involved Women: Executive Summary (Washington, DC: National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women, 2012), https://www.cjinvolvedwomen.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Ten_Truths_Brief.pdf.

9The Sentencing Project, Fact Sheet: Incarcerated Women and Girls, November 2020, http://www.sentencingproject.org/doc/publications/Incarcerated-Women-and-Girls.pdf.

10“Crime in the United States: Ten Year Arrest Trends by Sex, 2005–2014,” Federal Bureau of Investigation, accessed April 15, 2020, https://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/crime-in-the-u.s/2014/crime-in-the-u.s.-2014/tables/table-33.

11“Crime in the United States.”

12Lauren E. Glaze and Danielle Kaeble, Correctional Populations in the United States: 2013 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2014), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus13.pdf.

13Glaze and Kaeble, Correctional Populations in the United States: 2013.

14Aleks Kajstura and Russ Immarigeon, States of Women’s Incarceration: The Global Context (Northampton, MA: Prison Policy Initiative, 2015).

15Jaime M. Grant et al., Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey (Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality & National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 2011) 163, https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/resources/NTDS_Report.pdf.

16Marc Mauer, The Changing Racial Dynamics of Women’s Incarceration (Washington, DC: The Sentencing Project, 2013), https://www.sentencingproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/The-Changing-Racial-Dynamics-of-Womens-Incarceration.pdf.

17Lenora Lapidus et al., Caught in the Net: The Impact of Drug Policies on Women and Families (New York: American Civil Liberties Union, 2005), https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/2019-08/Report_Caught%20in%20the%20Net.pdf.

18The Sentencing Project, Fact Sheet.

19Matthew Durose, Alexia D. Cooper, and Howard N. Snyder, Recidivism of Prisoners Released in 30 States in 2005: Patterns from 2005 to 2010 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice,

Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2014), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/rprts05p0510.pdf.

20For more information on women’s pathways, see Bloom, Owen and Covington, Gender-Responsive Strategies; Tim Brennan, A Women’s Typology of Pathways to Serious Crime with Custody and Treatment Implications (Traverse City, MI: Northpointe, Inc., 2015); Tim Brennan et al., “Women’s Pathways to Serious and Habitual Crime: A Person-Centered Analysis Incorporating Gender-responsive Factors,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 39, no. 11 (2012): 1481–1508; Meda Chesney-Lind, The Female Offender: Girls, Women and Crime (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1997); Kathleen Daly, “Women’s Pathways to Felony Court: Feminist Theories of Lawbreaking and Problems of Representation,” Southern California Review of Law and Women’s Studies 2, no. 1 (1992): 11–52; Dana D. DeHart, Pathways to Prison: Impact of Victimization in the Lives of Incarcerated Women (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, 2005); Bonnie L. Green et al., “Trauma Exposure, Mental Health Functioning, and Program Needs of Women in Jail,” Crime & Delinquency 51, no. 1 (2005): 133–151; Lapidus et al., Caught in the Net: The Impact of Drug Policies on Women and Families; Emily J. Salisbury, “Gendered Pathways: An Empirical Investigation of Women Offenders’ Unique Paths to Crime” (PhD diss., University of Cincinnati, 2007).

21Ibid.

22Ibid.

23Ibid.

24Ibid.

25For further information on how this pathway more closely resembles male criminality, see Merry Morash, Women on Probation and Parole: A Feminist Critique of Community Programs and Services (Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press, 2010).

26Judith Berman, Women Offender Transition and Reentry: Gender Responsive Approaches to Transitioning Women Offenders from Prison to the Community (Center for Effective Public Policy for the National Institute of Corrections), https://www.cmcainternational.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Women-offender-transition-nd-reentry.pdf.

27Bloom, Owen, and Covington, Gender-Responsive Strategies.

28E. Ann Carson, Prisoners in 2014 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2015), table 11 (table title language updated).

29Carson, Prisoners in 2014; “Crime in the United States.”

30Doris J. James and Lauren E. Glaze, Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2006), http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji.pdf.

31Carson, Prisoners in 2014; “Crime in the United States.”

32Carson, Prisoners in 2014.

33Marilyn Van Dieten, Natalie J. Jones, and Monica Maria Rondon, Working With Women Who Perpetrate Violence: A Practice Guide (Washington, DC: National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women, 2014).

34Carson, Prisoners in 2014; “Crime in the United States.”

35Patricia L. Hardyman and Patricia Van Voorhis, Developing Gender-Specific Classification Systems for Women Offenders (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, 2004). Patricia Van Voorhis et al., “Women’s Risk Factors and Their Contributions to Existing Risk/Needs Assessment: The Current Status of a Gender-Responsive Supplement,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 37, no. 3 (2010): 261–288.

36Durose, Cooper, and Snyder, Recidivism of Prisoners.

37Ibid.

38Carson, Prisoners in 2014.

39Lauren E. Glaze and Laura M. Maruschak, Parents in Prison and Their Minor Children (U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2010), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/pptmc.pdf.

40J. Creasie Finney Hairston, Prisoners and Families: Parenting Issues During Incarceration (New York: Urban Institute, 2002) https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/60696/410628-Prisoners-and-Families-Parenting-Issues-During-Incarceration.pdf.

41Emily M. Wright et al., “Gender-Responsive Lessons Learned and Policy Implications for Women in Prison: A Review,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 39, no. 12 (2012): 1612–1632, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0093854812451088.

42Myrna Raeder, Pregnancy- and Child-Related Legal and Policy Issues Concerning Justice-Involved Women (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, 2013), https://s3.amazonaws.com/static.nicic.gov/Library/027701.pdf.

43Bloom, Owen, and Covington, Gender-Responsive Strategies.

44Ibid.

45Ibid.

46Jennifer Bronson and Marcus Berzofsky, Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011–12 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2017).

47“Gender and Women’s Mental Health,” World Health Organization, accessed April 15, 2020, https://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/genderwomen/en/.

48Ibid.; Nena Messina, Stacy Calhoun, and Jeremy Braithwaite, “Trauma-Informed Treatment Decreases Posttraumatic Stress Disorder among Women Offenders,” Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 15, no.1 (2014): 6–23.

49James and Glaze, Mental Health Problems.

50Bronson and Berzofsky, Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011–12.

51Ibid.

52Ibid.

53Patricia Kassebaum, Substance Abuse Treatment for Women Offenders (Collingdale, PA: Diane Publishing Company, 2004).

54Bronson and Berzofsky, Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2011–12.

55Jennifer Bronson et al., Drug Use, Dependence, and Abuse Among State Prisoners and Jail Inmates, 2007–2009 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2017), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/dudaspji0709.pdf.

56Ibid.

57Ibid.

58Shannon M. Lynch et al., Women’s Pathways to Jail: The Roles & Intersections of Serious Mental Illness & Trauma (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance, 2012).

59The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, Behind Bars II: Substance Abuse and America’s Prison Population (New York: The National Center for Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 2010).

60Bronson et al., Drug Use, Dependence, and Abuse.

61Ibid.

62Ibid.

63Kristine Riley, Elizabeth Swavola, and Ram Subramanian, Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform (New York: The Vera Institute of Justice, 2016), https://www.vera.org/downloads/publications/overlooked-women-and-jails-report-updated.pdf.

64Riley, Swavola, and Subramanian, Overlooked: Women and Jails in an Era of Reform.

65Lawrence A. Greenfeld and Tracy Snell, Women Offenders (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2000).

66Ibid.

67Angela Browne, Brenda Miller, and Eugene Maguin, “Prevalence and Severity of Lifetime Physical and Sexual Victimization Among Incarcerated Women,” International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 22, no. 3–4 (1999): 301–322; Green et al., “Trauma Exposure, Mental Health Functioning, and Program Needs of Women in Jail”; Shannon M. Lynch, April Fritch, and Nicole M. Heath, “Looking Beneath the Surface: The Nature of Incarcerated Women’s Experiences of Interpersonal Violence, Treatment Needs, and Mental Health,” Feminist Criminology 7, no. 4 (2012) 381–400; Lynch et al., Women’s Pathways to Jail: The Roles & Intersections of Serious Mental Illness & Trauma.

68Niki A. Miller and Lisa M. Najavits, “Creating Trauma-Informed Correctional Care: A Balance of Goals and Environment,” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 3 (2012): 1–8.

69Stephanie S. Covington, “A Woman’s Journey Home: Challenges for Female Offenders,” in Prisoners Once Removed: The Impact of Incarceration and Reentry on Children, Families, and Communities, ed. Jeremy Travis and Michelle Waul (Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press, 2003), 67–103.

70Allen J. Beck et al., Sexual Victimization in Prisons and Jails Reported by Inmates, 2011–12 (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2013), http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/svpjri1112.pdf; Nancy Wolff, Jing Shi, and Jane A. Siegel, “Patterns of Victimization among Male and Female Inmates: Evidence of an Enduring Legacy,” Violence and Victims 24, no. 4 (2009): 469–484, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3793850/.

71Ibid.

72Wright et. al, Gender-Responsive Lessons Learned.

73Ibid.

74Hardyman and Van Voorhis, Developing Gender-Specific Classification Systems.

75Emily Salisbury, “When Gender Neutral is Not Good Enough in Working with Justice Involved Women” (transcript of a session at the National Institute of Corrections Virtual Conference, November 9, 2016).

76For more information about the GINA, see Krista S. Gehring and Patricia Van Voorhis, “Needs and Pretrial Failure,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 41, no. 8 (2014): 943–970.

77Inquiries about the GINA should be made to Bauman Consulting Group, info@baumanconsultinggroup.com.

78For further information see “Northpointe Suite Case Manager,” Equivant, accessed April 20, 2020, https://www.equivant.com/northpointe-suite/.

79For further information see “SPIn-W Assessment,” Orbis Partners, accessed April 20, 2020, https://orbispartners.com/assessment/gender-responsive-spin-w/.

80Inquiries about the WRNA should be made to Dr. Emily J. Salisbury. Director, Utah Criminal Justice Center, Associate Professor, College of Social Work, emily.salisbury@utah.edu or (801) 581–4379.

81Van Voorhis et al., “Women’s Risk Factors.”

82“Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs),” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accessed April 20, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/acestudy/index.html.

83The LEC-5 is a public domain instrument available for download on the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website at https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp.

84“Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5),” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD, accessed April 20, 2020, https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp.

85The LSC-R is a public domain instrument available for download on the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website at https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/lsc-r.asp.

86“Life Stressor Checklist – Revised (LSC-R),” U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD, accessed April 20, 2020, https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/lsc-r.asp.

87The PCL-5 is a public domain instrument available for download on the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs website at https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp.

88“PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5),” National Center for PTSD, accessed April 20, 2020, https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp.

89“Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire – Revised,” Georgetown University, accessed April 20, 2020, https://georgetown.app.box.com/s/nzprmm2bn5pwzdw1l62w.

90“Case Management,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), accessed March 8, 2021, https://www.samhsa.gov/homelessness-programs-resources/hpr-resources/case-management.

91For a description of the CCW-W model see Orbis Partners, Inc., Women Offender Case Management Model (Ottawa, Ontario: Orbis Partners, Inc., 2006), https://s3.amazonaws.com/static.nicic.gov/Library/021814.pdf.

92 For further information, see “Collaborative Comprehensive Case Plans,” National Reentry Resource Center, accessed April 20, 2020, https://csgjusticecenter.org/nrrc/collaborative-comprehensive-case-plans/.

93 Renee Gobeil, Kelley Blanchette, and Lynn Stewart, “A Meta-Analytic Review of Correctional Interventions for Women Offenders: Gender-Neutral Versus Gender-Informed Approaches,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 43, no. 3, (2016): 301–322, https://www.centerforgenderandjustice.org/assets/files/meta-analyti-review-of-ci-final-criminal-justice-and-behavior-2016-gobeil-301-22.pdf.

94Some content adapted from Krista Gehring and Ashley Bauman, Gender-Responsive Programming: Promising Approaches (Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati, 2008); Van Voorhis et al., “Women’s Risk Factors.”

95 Lisa M. Najavits, A Woman’s Addiction Workbook: Your Guide to In-depth Healing (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, 2002).

96 Lisa M. Najavits et al., “A New Gender-Based Model for Women’s Recovery from Substance Abuse: Results of a Pilot Outcome Study,” The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 33, no. 5 (2007): 5–11.

97For information on the program, see Stephanie Covington, Beyond Trauma: A Healing Journey for Women (2nd Edition) (Center City, MN: Hazelden Publishing, 2016), https://www.stephaniecovington.com/beyond-trauma-a-healing-journey-for-women1.php.

98Messina, Calhoun, and Braithwaite, “Trauma-Informed Treatment”; Preeta Saxena, Nena P. Messina, and Christine E. Grella, “Who Benefits from Gender-Responsive Treatment? Accounting for Abuse History on Longitudinal Outcomes for Women in Prison,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 41, no. 4 (2014): 417–432.

99Oklahoma Department of Corrections, Helping Women Recover/Beyond Trauma: Program Effects on Offender Criminal Thinking, Psychological Adjustment, and Social Functioning (Oklahoma City: Oklahoma Department of Corrections Evaluation and Analysis Unit, 2013).

100Nena Messina, Stacy Calhoun, and Umme Warda, “Gender-Responsive Drug Court Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Criminal Justice and Behavior 39 (2012): 1536–1555; Stephanie Covington et al., “Evaluation of a Trauma-Informed and Gender-Responsive Intervention for Women in Drug Treatment,” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 5 (2008): 387–398.

101For further information on the program, see Stephanie Covington, Beyond Violence: A Prevention Program for Criminal Justice-Involved Women (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2013), https://www.stephaniecovington.com/beyond-violence-a-prevention-program-for-criminal-justice-involved-women1.php.

102Sheryl Kubiak et al., Long-Term Outcomes of a RCT Intervention Study for Women with Violent Crimes (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016); Nena Messina, Beyond Violence Final Report CDCR Cooperative Agreement No. 5600004087 (Sacramento, CA: California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 2014).

103Sheryl Kubiak, Evaluation of Specialized Substance Abuse Treatment Services for Women: Report of Long-Term Outcomes (East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, 2013), https://socialwork.msu.edu/sites/default/files/Project-Reports/MDOC-BV-Longterm-Outcomes-Report-0913.pdf.

104“Boston Consortium Model: Trauma-Informed Substance Abuse Treatment for Women,” SAMHSA’s National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices, accessed April 22, 2020, https://www.nurturingparenting.com/images/cmsfiles/npbostonconsortiummodel.pdf.

105Hortensia Amaro et al., “Effects of Trauma Intervention on HIV Sexual Risk Behaviors among Women with Co-Occurring Disorders in Substance Abuse Treatment,” Journal of Community Psychology 35, no. 7 (2007): 895–908.

106While DBT was not developed specifically for women involved in the justice system, it addresses abuse and trauma in a manner relevant to the population. For a description of DBT, see Marsha M. Linehan et al., Research on Dialectical Behavior Therapy: Summary of Non-RCT Studies (Seattle, WA: Behavioral Tech, 2016), https://behavioraltech.org/downloads/Research-on-DBT_Summary-of-Data-to-Date.pdf.

107Linda Dimeff, Kelly Koerner, and Marsha M. Linehan, Summary of Research on Dialectical Behavior Therapy (Seattle, WA: Behavioral Tech, 2002).

108Eric W. Trupin et al., “Effectiveness of a Dialectical Behavior Therapy Program for Incarcerated Female Juvenile Offenders,” Child and Adolescent Mental Health 7, no. 3 (2012): 121–127.

109Andrea Blanch, Beth Filson, and Darby Penney, Engaging Women in Trauma-Informed Support: A Guidebook (Washington, DC: National Center for Trauma-Informed Care, 2012).

110Ibid.

111For further information on the program, see Stephanie Covington, Helping Women Recover: A Program for Treating Addiction (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, rev. 2019), https://www.stephaniecovington.com/helping-women-recover-a-program-for-treating-substance-abuse.php.

112Mark P. McGovern et al., “A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing Integrated Cognitive Behavioral Therapy versus Individual Addiction Counseling for Co-occurring Substance Use and Posttraumatic Stress Disorders,” Journal of Dual Diagnosis 7, no. 4 (2011): 207–227.

113“Moving On,” Orbis Partners, Inc., accessed April 20, 2020, https://orbispartners.com/interventions/for-females/moving-on/.

114Ibid.

115Krista S. Gehring and Valerie Bell, “What Works” for Female Probationers? An Evaluation of the Moving On Program (Cincinnati, OH: University of Cincinnati, 2010).

116Naama Tokayer, A Brief Note on Research Support for the Risking Connection® Approach (Derwood, MD: Sidran Institute, 2001).

117David C. Wright, “An Investigation of Trauma-Centered Inpatient Treatment for Adult Survivors of Abuse,” Child Abuse and Neglect 27 (2003): 393–406.

118Ann Jennings, Models for Developing Trauma-Informed Behavioral Health Systems and Trauma-Specific Services (Washington, DC: National Center for Trauma-Informed Care, 2008).

119For further information on the program, see “The Model Seeking Safety,” Treatment Innovations, accessed April 21, 2020, https://www.treatment-innovations.org/seeking-safety.html.

120“Seeking Safety: Evidence,” Treatment Innovations, accessed April 21, 2020, https://www.treatment-innovations.org/evidence.html.

121Lisa M. Najavitz et al., “Peer-Led Seeking Safety: Results of a Pilot Outcome Study with Relevance to Public Health,” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs 46, no. 4 (2014): 295–302.

122Stephen Tripodi et al., “Evaluating Seeking Safety for Women in Prison: A Randomized Controlled Trial,” Research on Social Work Practice 29, no. 3 (2017): 281–290.

123Shannon M. Lynch et al., “Seeking Safety: An Intervention for Trauma-Exposed Incarcerated Women?” Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 13 (2012): 88–101.

124Dusty Miller and Laurie Guidry, Addictions and Trauma Recovery (New York: W.W. Norton Company, 2001).

125Joseph P. Morrissey et al., “Twelve-month Outcomes of Trauma-Informed Interventions for Women with Co-occurring Disorders,” Psychiatric Services 56 (2005): 1213–1222.

126See the New York State Corrections and Community Supervision facilitator’s manual, Trauma Addictions Mental Health and Recovery (TAMAR) Treatment Manual and Modules (Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, 2019), https://www.nasmhpd.org/content/trauma-addictions-mental-health-and-recovery-tamar-treatment-manual-and-modules.

127Ann Jennings, Models for Developing Trauma-Informed Behavioral Health Systems and Trauma-specific Services (Alexandria, VA: National Technical Assistance Center for State Mental Health Planning, National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, 2004).

128“Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education & Therapy,” Advanced Trauma Solutions Professionals, accessed May 5, http://www.advancedtrauma.com/Services.html.

129For information on positive outcomes related to TARGET, see “TARGET Evidence & Research,” Advanced Trauma Solutions Professionals, accessed May 5, http://www.advancedtrauma.com/Evidence—Research.html.

130Jennings, Models for Developing Trauma-Informed Behavioral Health Systems.

131Ibid.

132Shelly F. Greenfield, Treating Women with Substance Use Disorders: The Women’s Recovery Group Manual (New York: Guilford Press, 2016).

133Shelly F. Greenfield et al., “The Women’s Recovery Group Study: A Stage I Trial of Women-Focused Group Therapy for Substance Use Disorders versus Mixed-Gender Group Drug Counseling,” Drug and Alcohol Dependence 6, no. 90 (2007): 39–47; Dawn E. Sugarman et al., “Measuring Affiliation in Group Therapy for Substance Use Disorders in the Women’s Recovery Group Study: Does It Matter Whether the Group Is All-Women or Mixed-Gender?” The American Journal on Addictions 25, no. 7 (2016): 573–580.

134Jeanne Obert, Edythe D. London, and Richard A. Rawson, “Incorporating Brain Research Findings into Standard Treatment: An Example Using the Matrix Model,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 23 (2002): 107–113; Alice Huber et al., “Integrating Treatments for Methamphetamine Abuse: A Psychosocial Perspective,” Journal of Addictive Diseases 16, no. 4 (1997): 41–50.

Project Credits

Writing: Elizabeth Fleming, CSG Justice Center; Allison Upton, CSG Justice Center; Felicia Lopez Wright, CSG Justice Center; Sarah Wurzburg, CSG Justice Center; Becki Ney, Center for Effective Public Policy/National Resource Center on Justice Involved Women

Advising: Sarah Wurzburg, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Darby Baham, Leslie Griffin, Emily Morgan, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Web Development: Andrew Currier, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Ruvi Lopez, CSG Justice Center

© 2021 by The Council of State Governments Justice Center

Suggested Citation:

Elizabeth Fleming et al., Adopting a Gender-Responsive Approach for Women in the Justice System: A Resource Guide (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2021).

ABOUT THE AUTHORS