Availability of Defendants’ Race and Ethnicity Information in Montana’s Case Management System

Availability of Defendants’ Race and Ethnicity Information in Montana’s Case Management System

Between April 2021 and February 2022, The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center conducted an analysis of racial equity across Montana’s criminal justice system in partnership with Montana judicial branch stakeholders. This report had two main objectives: (1) to explore patterns in how information about race is collected in the Montana court case management system and (2) to analyze the availability of data on presentence investigations (PSIs). Key findings were that race information about defendants was missing in 32 percent of cases filed between 2015 and 2020; municipal courts and justice courts recorded race far more frequently than district courts and city courts; there was considerable variation in the availability of race information by judicial district and court; and PSIs were requested in fewer than 50 percent of felony cases filed between January 2018 and December 2020. Based on these findings, the CSG Justice Center proposed five recommendations to improve the quantity and quality of race information collected.

Introduction

Between April 2021 and February 2022, with funding from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center conducted an analysis of racial equity across Montana’s criminal justice system in partnership with Montana judicial branch stakeholders. This project builds on previous work done by CSG Justice Center staff in Montana as part of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI), which documented initial evidence of racial disparities between White and American Indian people in arrests and in corrections populations.1

Prior to the launch of this project, CSG Justice Center staff anticipated that there could be limitations in race and ethnicity data available in the court record system due to inconsistent data collection practices across Montana courts. After an initial analysis of court data, CSG Justice Center staff determined that a rigorous analysis of racial equity (e.g., using regression analysis) using court data could not be conducted because of the high level of missing race and ethnicity information about defendants.

However, data from the Montana Department of Corrections (MT DOC), though limited to people convicted of a felony offense, had near complete race and ethnicity information. Thus, CSG Justice Center staff were able to complete a statistical analysis of racial equity at some decision-making points using MT DOC data. This analysis found consistent evidence of racial disparities between White and American Indian people at several decision points in the judicial system, including incarceration for felony person and public order offenses; length of stay in secure or alternative secure facilities; and revocations from probation, conditional release, and parole.2

With court data limitations in mind, the analysis documented in this report had two main objectives: (1) to explore patterns in how information about race is collected across the court system and (2) to analyze the availability of data on presentence investigations (PSIs), since a new policy on PSIs was implemented in 2018. CSG Justice Center staff examined all misdemeanor and felony cases filed in Montana courts between 2010 and 2020 and looked to see which cases included the race and ethnicity of the defendant in the FullCourt case management system. Recommendations for the Montana Judiciary to improve the quantity and quality of race information recorded in their case management system are also presented. Additionally, using PSI data from the MT DOC, CSG Justice Center staff explored PSI information and examined how frequently PSIs were requested and completed.

Data Sources

FullCourt is Montana’s statewide court case management system. The Information Technology Division of the Office of the Court Administrator is in the process of coordinating the transition from FullCourt Version 5 to FullCourt Enterprise across the state. As of September 2020, 19 of the 211 courts had transitioned to the new FullCourt implementation.3

The courts dataset analyzed for this project was obtained via a data use agreement between the CSG Justice Center and the Montana Judiciary. Staff from the Office of the Court Administrator extracted and shared all criminal charges filed in Montana courts between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2020. There were 2,717,976 felony and misdemeanor charges filed in district courts and courts of limited jurisdiction during this period. By grouping together charges filed on the same day with the same case number, CSG Justice Center staff identified a total of 1,953,918 cases. Much of the following analysis is limited to cases filed between 2015 and 2020, during which time there were 986,363 cases filed.

Data about PSI requests and completions were obtained from the MT DOC Offender Management Information System (OMIS). CSG Justice Center staff analyzed 8,286 cases in which people were sentenced for a felony offense between July 1, 2018, and December 31, 2020. Further information on MT DOC data is available in the accompanying CSG Justice Center report, Racial Equity in Montana’s Criminal Justice System.4

Additionally, in fall 2021 and winter 2022, CSG Justice Center staff conducted interviews with judges and clerks in three counties, as well as state supreme court staff, to obtain information on court administrative processes. Staff from the Montana Judiciary’s Office of the Court Administrator and Court Information Technology Program, as well as the MT DOC Statistics and Data Quality Unit, were also consulted to confirm the validity of the data analyzed.

Results

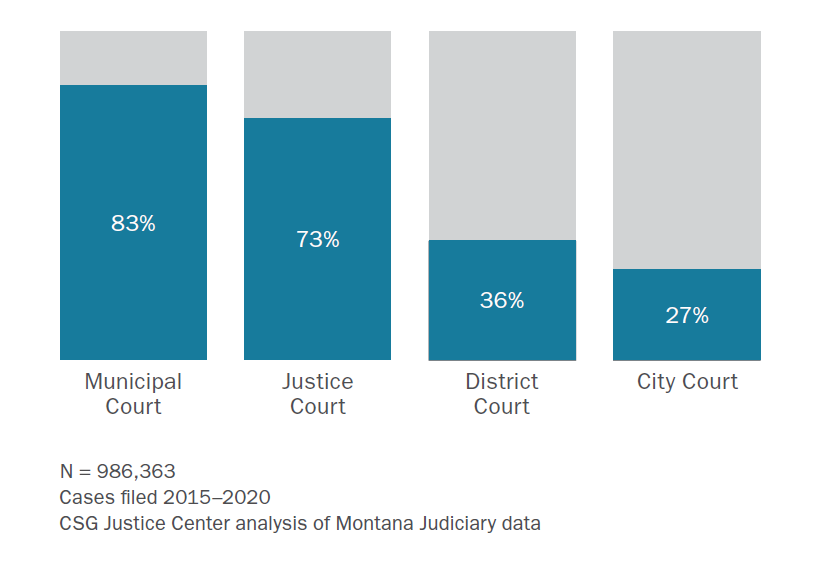

Statewide, across all court types, 68 percent of cases filed between 2015 and 2020 included the race of the defendant; 32 percent of cases were missing this information. There was significant variation across court types, judicial districts, and individual courts in the amount of race information collected, indicating inconsistent business processes and quality assurance across courts in how race is recorded.

Summary of Results

■ Race information about defendants was missing in 32 percent of cases filed between 2015 and 2020.

■ Statewide, municipal courts and justice courts recorded race far more frequently than district courts and city courts.

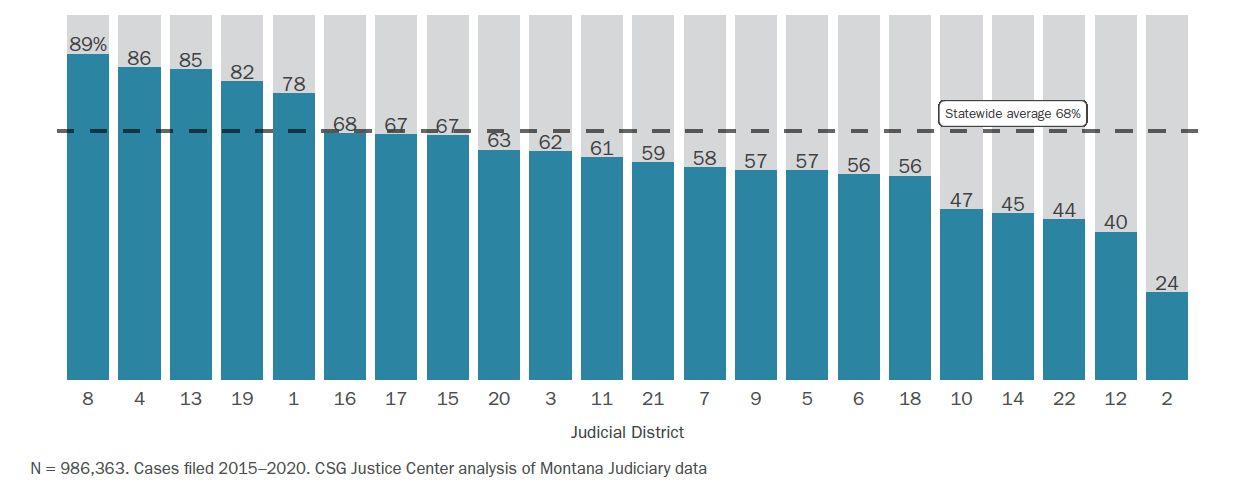

■ There was considerable variation in the availability of race information by judicial district and court. Five judicial districts collected race in more than 75 percent of cases filed, while 5 judicial districts collected race in fewer than 50 percent of cases.

■ PSIs were requested in fewer than 50 percent of felony cases filed between January 2018 and December 2020. PSIs were requested at similar rates for White and American Indian defendants.

Court Type

In Montana, district courts hear all felony cases, while courts of limited jurisdiction hear misdemeanor cases (though in some jurisdictions, a felony case may first be filed in a lower court and then transferred to a district court).5 There are three types of courts of limited jurisdiction: justice courts, city courts, and municipal courts. The jurisdiction of these courts varies slightly, but generally they hear similar types of cases. There are 56 district courts within 22 judicial districts.6 There are 61 justice courts, 84 city courts, and 6 municipal courts.7

Between 2015 and 2020, the majority of cases were filed in justice courts: specifically, 53 percent (523,719) of all criminal cases and violations were filed in justice courts, 29 percent (280,853) were filed in municipal courts, and 14 percent (135,839) were filed in city courts. Only 5 percent (45,952) of cases were filed in district courts.

Municipal courts recorded race information about defendants in more than 80 percent of cases, and justice courts recorded it in nearly three-quarters of cases filed. City courts and district courts, however, collected race information far less frequently.

Figure 1: Cases with Information Available about Defendant Race by Court Type

The higher rates of race information collected in courts of limited jurisdiction are not surprising. Because these courts hear misdemeanor and violation-type cases, many of the cases filed include a ticket or citation issued by a law enforcement agency. While the citations themselves may not include race information, some demographic details about defendants (including race) are automatically imported from law enforcement data systems along with the citation into FullCourt.8 This automatic import does not happen across all local law enforcement agencies but could be a model for how to increase the amount of race information in FullCourt.

For felony cases filed in district court, this citation is less often available, and district court clerks rely on law enforcement agencies forwarding Montana Arrest Numbering System (MANS) forms to the court to enter race information about defendants. MANS forms are created by law enforcement agencies after an arrest and include the date of arrest, charges, and arresting agencies, as well as name, date of birth, social security number, sex, race, and other demographic characteristics of the person arrested.9 When a defendant in district court does not have an arrest record available, some courts send defendants to a local jail to do a “Book and Release,” in which the defendant is fingerprinted and a MANS form is created.10 Following the arrest or fingerprinting, MANS forms are generally forwarded to county attorneys or courts where additional charging information is added. County attorneys then forward MANS forms to the court along with other charging documents where clerks enter the information on the MANS form into the FullCourt case management system.11

In district courts and courts of limited jurisdiction, court staff whom CSG Justice Center staff spoke to reported that they do not enter the race of a defendant in the case management system unless it is available on a MANS form or citation.12 In other words, the race data collected by court clerks always come from secondary sources. When race is not available from these sources, no race information is entered into FullCourt.

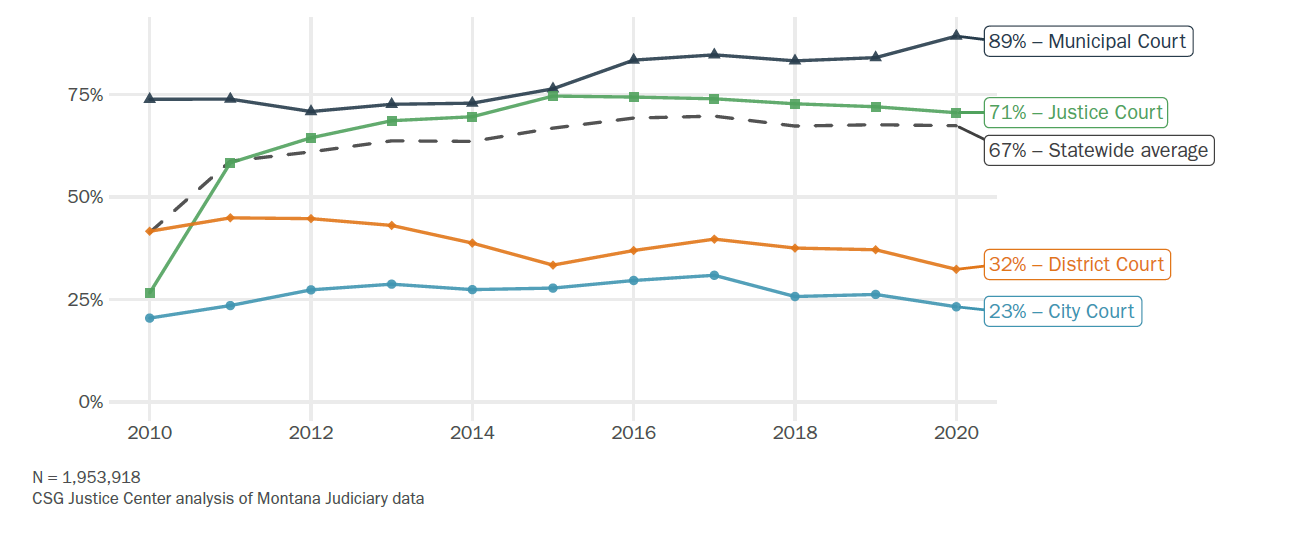

Statewide, the percentage of cases filed with race recorded has greatly improved since 2010, when only 31 percent of cases had race information available. The year with the highest overall percentage was 2017, when 70 percent of all cases filed had race recorded. Since then, there has been a slight decline to 67 percent.

Since 2010, municipal courts (+15 percentage points), justice courts (+44), and city courts (+3) have increased the percentage of race information recorded, while the rates for district courts (–9) have fallen.

The longer-term trends for all court types are generally positive, but in the most recent year for which data are available, justice courts, district courts, and city courts were all below their peaks in prior years. Between 2019 and 2020, the rate of race collected by district courts fell from 37 percent to 32 percent. One potential driver of this decrease is that many law enforcement agencies were not conducting “Book and Releases” due to the COVID-19 pandemic.13

Figure 2: Cases with Information Available about Defendant Race by Court Type

Figure 3: Cases with Information Available about Defendant Race by Judicial District

Judicial District

The rate of race information collected varied widely across Montana’s 22 judicial districts. Between 2015 and 2020, the Eighth Judicial District (Cascade County) collected race in 89 percent of cases filed, the highest rate of all districts. The Fourth Judicial District (Mineral and Missoula Counties) recorded race in 86 percent of cases filed. The Second Judicial District (Silver Bow County) collected race information for 24 percent of its cases, the lowest rate in the period examined.

Additional analysis of court types within judicial districts revealed substantial variation. For instance, between 2015 and 2020, 61 percent of all cases in the Eleventh Judicial District (Flathead County) had race information recorded. But the Columbia Falls City Court recorded race in 97 percent of cases (7,385 out of 7,639 cases), while the Flathead County District Court only recorded race in 10 percent of cases (311 out of 3,105 cases). The 3 remaining courts in the Eleventh District recorded 79 percent (Flathead County Justice Court), 50 percent (Whitehead Municipal Court), and 32 percent (Kalispell Municipal Court) of race information. This intradistrict variation was not uncommon across judicial districts and suggests that practices are inconsistent across districts, court types, and individual courts.

Court

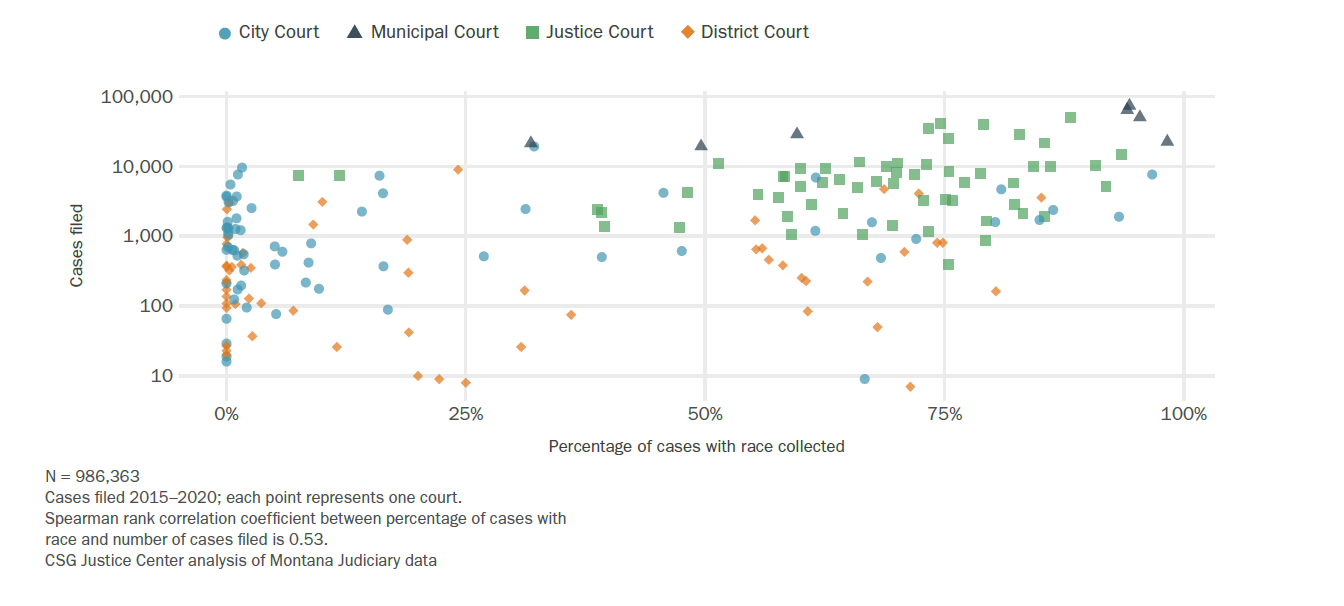

In addition to differences by court type and judicial district in the amount of race information collected, there was a lot of variation among individual courts. In general, courts that heard more cases also collected a larger percentage of race information. This is not wholly surprising, as larger courts may have more resources and staff dedicated to case processing and data entry. Despite this trend, there were some large courts that had challenges collecting race information and some smaller courts that were very successful in recording race.

Figure 4: Cases with Information Available about Defendant Race by Court

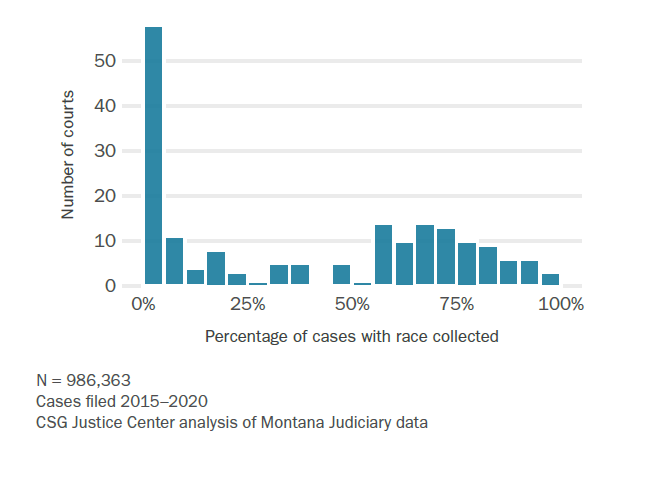

As can be seen in Figure 4, there are 2 main clusters of courts: those that collected race in fewer than 10 percent of cases and those that collected race for between 60 and 90 percent of cases. In fact, there were 58 courts that recorded the race of the defendant in fewer than 5 percent of cases between 2015 and 2020. On the other hand, 9 courts recorded race information in more than 90 percent of cases.

This court-level variation suggests disparate practices and business processes by courts in recording race information. It is possible some courts have stronger relationships with local law enforcement agencies and county attorney staff, enabling the courts to receive a greater proportion of citations and MANS forms generated. It is also possible that some courts and clerks prioritize collecting this information more than other courts.

Figure 5: Number of Courts with Percentage of Cases Filed with Information Available about Defendant Race

Presentence Investigations

As a part of JRI, Senate Bill (SB) 60 (2017) required Montana to adopt a new set of presentence investigation (PSI) practices.14 The goal of this legislation was to revamp the PSI report to be more structured and objective, encourage the use of evidence-based practices in sentencing, and require PSIs to be produced in a timely fashion. Notably, SB 60 required the results of a risk and needs assessment tool to be incorporated into the PSI to help judges set appropriate conditions of supervision and required MT DOC to complete PSIs within 30 days (this was later amended to 30 business days in the next legislative session).15 During the JRI implementation phase, CSG Justice Center staff provided guidance to MT DOC on the creation of the new PSI template and incorporating best practices for the use of risk and needs assessment results in the PSI, including a webinar for judges. CSG Justice Center staff also encouraged MT DOC to set up a data tracking system for PSIs that focused on tracking the timeliness of PSI completion. However, currently, limited fields related to the PSI are tracked by MT DOC: whether a PSI was requested, whether it was completed, and when these events took place. Nearly 100 percent of PSI requests are completed, indicating that MT DOC is consistently carrying out requests made by judges. At the same time, though, among cases sentenced between July 2018 and December 2020, PSIs were requested in only 56 percent of felony cases (see Table 1). Although there was no statistically significant difference in the use of PSIs for American Indian and White people, no data were available to determine why PSIs are so infrequently requested. It is possible that judges are choosing not to request a PSI when one has been conducted recently.16 However, additional data collection and analysis would be needed to investigate this potential explanation systematically.

Table 1: Use of PSIs by Defendant Race

| Defendant Race | No PSI Requested Pct. (Count) | PSI Requested Pct. (Count) |

| American Indian | 43.5% (763) | 56.5% (990) |

| White | 44.3% (2,896) | 55.7% (3,637) |

| Total | 44.2% (3,659) | 55.8.% (4,627) |

N = 8,286. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding. Analysis limited to original sentences involving American Indian and White people convicted of a felony offense and sentenced between July 2018 and December 2020. Nearly 100 percent of PSIs requested were also completed by MT DOC staff during this period. Chi-square tests were used to examine the relationship between defendant race and PSI requests; however, no statistically significant difference was found (X2=0.36, p=0.55).

Recommendations

Based on the analysis of missing race and ethnicity information as well as interviews with judges, clerks, and court administrators, CSG Justice Center staff have developed four major policy recommendations for improving the amount of race information captured by the courts:

1. Standardize how race and ethnicity are captured and recorded in FullCourt and allow parties in court cases to self-identify their race at an appropriate juncture in the court process.

2. Improve the capacity for data sharing and data exchanges between state agencies and across IT systems and work with state and local law enforcement to codify how and where race information is collected.

3. Build capacity to report on race information collected in FullCourt.

4. Prioritize collecting race information in district courts.

Within each of these broad recommendations, further recommendations for how best to address these areas are proposed. Two additional recommendations related to improving data collection for PSIs and other FullCourt data improvements are also presented.

Standardization of Race Information Collected

The National Open Court Data Standards (NODS)17 were developed by the Conference of State Court Administrators and the National Center for State Courts as a template for how to record race, ethnicity, and other information about court proceedings in case management systems. The Montana Judiciary should restructure the FullCourt Enterprise case management system to align with NODS. The NODS project recommends capturing the race and ethnicity of defendants as well as the source of this information. NODS specifies six data elements to fully capture race and ethnicity:

■ Race

■ Race source

■ Race self-identified or observed

■ Ethnicity

■ Ethnicity source

■ Ethnicity self-identified or observed

Separating race and ethnicity into two elements aligns with U.S. Office of Management and Budget guidelines,18 acknowledges the varied racial backgrounds of people who identify as Hispanic or Latino, and allows for more detailed sub-group analysis. The race and ethnicity source elements represent the source or agency where the race or ethnicity data were collected and may include values such as driver’s license, jail, law enforcement, prosecutor, etc. The self-identified or observed elements are indicators for whether the source relies upon self-report by the defendant or an observation from someone else. In addition to the race element, Montana courts may want to include an additional field in FullCourt to capture Tribal affiliation. The Court Statistics Project advises that courts “consider expanding the [race] categories they collect to fit the needs of their community.”19

The NODS project recommends self-identification as the preferred method of race and ethnicity data collection because of increased accuracy compared to observed race.20 The Montana Judiciary should convene a working group to develop a system for defendants to self-identify their race, ethnicity, and Tribal affiliation. Key stakeholders for this working group would include the Office of Court Administrator, district courts and court of limited jurisdiction automation committees, county attorneys, the Office of State Public Defenders, and others. There could be an option to self-identify race and ethnicity in documents submitted by attorneys on behalf of their clients or as part of a check-in system at the courts. For cases in which PSIs are conducted, this is another time when defendants could be given the opportunity to identify their race and ethnicity. The court should note that providing race and ethnicity information is optional, will be used for statistical purposes only, and will not be used in any way during the court proceedings. Despite the potential for improved accuracy of race and ethnicity when it is self-reported, it is possible that asking for defendants’ race could raise concerns about whether providing this information could impact their case. Therefore, any direct request for race information from defendants should be posed thoughtfully and with sensitivity to these concerns.

Once the technical systems are in place, it will also be important to develop quality assurance processes to ensure the consistency of the data collected. The judiciary should create a standard operating procedure manual and training for court clerks to standardize and improve business processes including how, when, and where race and other demographic information is recorded in FullCourt. The standard operating procedures should also include recommendations for court clerks on how to perform quality assurance checks on data entered into FullCourt. Since there is wide variation in the amount of race information collected by courts, courts that successfully collect large amounts of data could be used as exemplars, and their business processes could be used as models to develop these standard operating procedures.

Data Sharing and Data Exchanges

The Montana Judiciary should continue collaborating with the Montana Department of Justice (DOJ), the MT DOC, and other state agencies to improve data sharing across information technology systems. If information about defendants could be automatically transferred from DOJ systems containing arrest and booking details to FullCourt Enterprise, reliance on Montana arrest numbering system (MANS) forms and citations to obtain defendant demographic details would be minimized, and court clerks could spend more time confirming the quality and accuracy of information in FullCourt, rather than entering data. This recommendation aligns with the 2021 Montana Judicial Branch Information Technology Strategic Plan21and the results of a 2017 legislative audit of the IJIS Broker system.22 Additionally, in 2021, the Montana Legislature requested an interim study of the “collection and dissemination of criminal justice system data.”23 This study was assigned to the Law and Justice Committee, which met in October 2021 to begin their review.24 The results of this interim study could set the stage for some of the statewide data improvements recommended here.

To make the data exchanges between criminal justice agencies’ data systems effective, the judiciary, DOJ, MT DOC, and other state agencies should create a single, statewide individual identification number that uniquely identifies a person across multiple data systems. With this unique identifier, race and other demographic information about a person could be more reliably captured, matched, and updated across systems. If this is accomplished, it would further improve quality assurance efforts, allowing for automated verification of whether the race and ethnicity fields are consistent for individuals across all data systems. For example, an automated program could be developed to check for inconsistencies between systems and allow the agencies to correct data as needed.

The judiciary should also work with state and local law enforcement agencies to standardize the information that is collected in violations and citations and ensure that race and ethnicity are captured on the common forms and templates used by law enforcement agencies. Even if there are opportunities for defendants to self-report race and ethnicity, information that is collected by law enforcement would still be essential to increasing the total percentage of race data recorded in FullCourt.

Reporting and Reassessment

To promote transparency and encourage local courts to comply with best practices for collecting race and ethnicity information, the Montana Judiciary should work toward a long-term goal of regularly reporting and reassessing the quality and completeness of court data on race and ethnicity. The value of collecting more accurate and consistent race information in FullCourt would be amplified by a strategic plan to publish this data to inform policy and practice. In 2020, the Conference of Chief Justices and Conference of State Court Administrators recognized that courts in many states have initiated efforts “to collect, maintain and report court data regarding race and ethnicity that enables courts to identify and remedy racial disparities.”25 The Montana Board of Crime Control has developed interactive reports of crime data that include information disaggregated by race26 and could be a model for how the judiciary publishes this data, given sufficient resources.

As discussed in Racial Equity in Montana’s Criminal Justice System, the CSG Justice Center was hindered in its ability to assess racial disparities because there is not sufficient race information captured in FullCourt to reliably draw statistical conclusions.27 The current project was limited to analyzing racial disparities for people convicted of felonies using MT DOC data. If the Montana courts can increase the proportion of cases with race information recorded, a fuller assessment of disparities should be conducted. This assessment could cover a broader range of cases and decision-making points across the system, including dispositions in misdemeanor cases, pretrial incarceration, bond amounts, pleas, and conviction and dismissal rates for felony cases. Importantly, the Montana Judiciary does not currently have the resources to conduct regular reporting and reassessment of race and ethnicity data, but additional staff capacity could support the use and publication of this data.

District Courts

Even though district courts account for the smallest percentage of cases filed in Montana courts, they hear the most serious cases and have lower rates of race information available than municipal courts and justice courts. Moreover, Racial Equity in Montana’s Criminal Justice System showed there are disparities in incarceration decisions between American Indian and White people convicted of felonies.28 The judiciary should prioritize increasing the rate of race information collected in district courts by collaborating with district court clerks of court, court automation committees, and local law enforcement agencies. Lewis and Clark County District Court and Teton County District Court recorded race information in more than 80 percent of cases filed between 2015 and 2020. These two courts could serve as models for large and small courts in how to effectively collect race information.

Data Collection for Presentence Investigations

CSG Justice Center racial equity analysis of MT DOC data indicated that there are American Indian-White disparities at sentencing for person and public order offenses. Specifically, relative to comparable White people, American Indian people are 1.5 times more likely to receive an incarceration sentence for a felony person offense and are 1.4 times more likely to receive an incarceration sentence for a felony property offense.29 Given this evidence, it would be beneficial to investigate more closely whether there is room to refine current practices in the use of PSIs. Collecting more detailed data on how PSIs are used will improve capacity to understand the implementation of this policy better and determine whether PSI use could potentially be refined to help address racial disparities at sentencing.

Currently, PSI information in FullCourt is limited to dates of when PSIs are ordered by judges and received from MT DOC.30 However, the courts could create a field to record a reason when a PSI is not requested, for example. This field might include pre-populated options such as “PSI completed during previous 12 months” and any other frequently cited reasons, as well as an “Other” option that allows for a short text entry. Additionally, completed PSI information is stored in FullCourt as a scanned PDF, which doesn’t allow for aggregate analysis of PSIs. If information from PSIs were stored as normalized data in FullCourt, analysis of racial disparities in PSI results and how they are used in sentencing could be further investigated.

Additional FullCourt Improvements

This report mostly focuses on improving the collection of race and ethnicity information in FullCourt, but during the analysis, CSG Justice Center staff identified additional opportunities to improve the quality of data in FullCourt. One general challenge in analyzing the existing FullCourt data was that many fields are not used consistently across courts. Further, some fields that could be populated using drop-down menus with a constrained set of responses instead allow for free-text entry, which makes analysis more difficult or impossible. For example, there is no standard set of responses for key case information, such as disposition.

There are also additional fields that could be captured in FullCourt to allow for more in-depth analysis of court processes. Two areas of interest are pleas (e.g., original charges, reduced charges, pleas offered, pleas accepted) and judicial placement recommendations made to MT DOC for people sentenced to DOC commit. It is also important for future research that all courts consistently collect and enter final disposition data in a machine-readable format (i.e., not through a PDF file).

Conclusion

This report presented findings from an analysis of how information about race is collected across the Montana court system as well as the availability of data on PSIs. Race information about defendants was not available in 32 percent of cases filed in Montana between 2015 and 2020. In district courts, where the most serious cases are heard, 64 percent of cases did not have race information available. Municipal courts and justice courts collected race information in more than 75 percent of cases. Additionally, there was large variation in the amount of race information recorded by judicial district and individual court. In some judicial districts, race information was available for more than 80 percent of cases, while in others, it was available for less than 50 percent of cases. Fifty-three courts collected race in fewer than 5 percent of cases filed.

Since the new policy on PSIs was implemented in 2018, PSIs were requested in 44 percent of felony cases. There were no differences observed in the frequency of PSIs requested between White and American Indian defendants. Of the PSIs that were requested, nearly all were completed.

The findings from the accompanying report, Racial Equity in Montana’s Criminal Justice System, serve as important context for this report on missing data in Montana’s court case management system. Those findings show racial disparities between White and American Indian defendants in the likelihood to be sentenced to prison, the amount of time spent incarcerated, and the rate of revocation from probation or conditional release for technical violations.31 But, without more complete race information about defendants, it is difficult to fully assess racial disparities in Montana courts. The CSG Justice Center was only able to explore differences by race in people convicted of felonies because of the high level of missing data in the court case management system. If the judiciary can improve the quantity and quality of race information collected by applying the recommendations included in this report, more thorough and complete analysis of racial disparities at additional points in the Montana court system will be possible.

Appendix

Number of Cases Filed in District Courts with Race Information Available, 2015–2020

| Judicial District | Court | Cases Filed | Cases with Race | % Cases with Race |

| 1 | Broadwater County District Court | 300 | 57 | 19.0% |

| 1 | Lewis & Clark County District Court | 3,567 | 3,036 | 85.1% |

| 2 | Butte-Silver Bow County District Court | 1,688 | 932 | 55.2% |

| 3 | Anaconda-Deer Lodge County District Court | 577 | 10 | 1.7% |

| 3 | Granite County District Court | 94 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 3 | Powell County District Court | 770 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 4 | Mineral County District Court | 364 | 2 | 0.5% |

| 4 | Missoula County District Court | 4,077 | 2,948 | 72.3% |

| 5 | Beaverhead County District Court | 389 | 6 | 1.5% |

| 5 | Jefferson County District Court | 366 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 5 | Madison County District Court | 172 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 6 | Park County District Court | 807 | 599 | 74.2% |

| 6 | Sweet Grass County District Court | 110 | 4 | 3.6% |

| 7 | Dawson County District Court | 672 | 376 | 56.0% |

| 7 | McCone County District Court | 26 | 3 | 11.5% |

| 7 | Prairie County District Court | 42 | 8 | 19.0% |

| 7 | Richland County District Court | 964 | 1 | 0.1% |

| 7 | Wibaux County District Court | 10 | 2 | 20.0% |

| 8 | Cascade County District Court | 4,723 | 3,244 | 68.7% |

| 9 | Glacier County District Court | 382 | 222 | 58.1% |

| 9 | Pondera County District Court | 128 | 3 | 2.3% |

| 9 | Teton County District Court | 163 | 131 | 80.4% |

| 9 | Toole County District Court | 228 | 138 | 60.5% |

| 10 | Fergus County District Court | 459 | 260 | 56.6% |

| 10 | Judith Basin County District Court | 75 | 27 | 36.0% |

| 10 | Petroleum County District Court | 7 | 5 | 71.4% |

| 11 | Flathead County District Court | 3,105 | 311 | 10.0% |

| 12 | Chouteau County District Court | 107 | 1 | 0.9% |

| 12 | Hill County District Court | 890 | 168 | 18.9% |

| 12 | Liberty County District Court | 27 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 13 | Yellowstone County District Court | 8,973 | 2,171 | 24.2% |

| 14 | Golden Valley County District Court | 26 | 8 | 30.8% |

| 14 | Meagher County District Court | 37 | 1 | 2.7% |

| 14 | Musselshell County District Court | 215 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 14 | Wheatland County District Court | 86 | 6 | 7.0% |

| 15 | Daniels County District Court | 20 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 15 | Roosevelt County District Court | 224 | 150 | 67.0% |

| 15 | Sheridan County District Court | 137 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 16 | Carter County District Court | 8 | 2 | 25.0% |

| 16 | Custer County District Court | 649 | 359 | 55.3% |

| 16 | Fallon County District Court | 84 | 51 | 60.7% |

| 16 | Garfield County District Court | 23 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 16 | Powder River County District Court | 50 | 34 | 68.0% |

| 16 | Rosebud County District Court | 236 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 16 | Treasure County District Court | 9 | 2 | 22.2% |

| 17 | Blaine County District Court | 167 | 52 | 31.1% |

| 17 | Phillips County District Court | 109 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 17 | Valley County District Court | 253 | 152 | 60.1% |

| 18 | Gallatin County District Court | 2,995 | 9 | 0.3% |

| 19 | Lincoln County District Court | 806 | 603 | 74.8% |

| 20 | Lake County District Court | 2,437 | 1 | 0.0% |

| 20 | Sanders County District Court | 379 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 21 | Ravalli County District Court | 1,467 | 133 | 9.1% |

| 22 | Big Horn County District Court | 596 | 422 | 70.8% |

| 22 | Carbon County District Court | 353 | 9 | 2.5% |

| 22 | Stillwater County District Court | 324 | 1 | 0.3% |

Number of Cases Filed in Justice Courts with Race Information Available, 2015–2020

| Judicial District | Court | Cases Filed | Cases with Race | % Cases with Race |

| 1 | Broadwater County Justice Court | 9,283 | 5,566 | 60.0% |

| 1 | Lewis and Clark County Justice Court | 25,010 | 18,849 | 75.4% |

| 2 | Silver Bow County Justice Court Dept. 1 | 7,359 | 870 | 11.8% |

| 2 | Silver Bow County Justice Court Dept. 2 | 7,417 | 554 | 7.5% |

| 3 | Deer Lodge County Justice Court | 11,571 | 7,644 | 66.1% |

| 3 | Granite County Justice Court 1 (Phillipsburg) | 4,292 | 2,067 | 48.2% |

| 3 | Powell County Justice Court | 10,130 | 8,535 | 84.3% |

| 4 | Mineral County Justice Court | 9,931 | 8,544 | 86.0% |

| 4 | Missoula County Justice Court of Record | 41,114 | 30,670 | 74.6% |

| 5 | Beaverhead County Justice Court, Dept 1 | 8,573 | 6,470 | 75.5% |

| 5 | Jefferson County Justice Court | 9,960 | 6,864 | 68.9% |

| 5 | Madison County Justice Court | 5,937 | 3,695 | 62.2% |

| 6 | Big Horn County Justice Court | 7,281 | 4,231 | 58.1% |

| 6 | Park County Justice Court | 10,618 | 7,761 | 73.1% |

| 6 | Sweet Grass County Justice Court | 3,272 | 2,381 | 72.8% |

| 7 | Dawson County Justice Court | 9,217 | 5,767 | 62.6% |

| 7 | McCone County Justice Court | 1,054 | 622 | 59.0% |

| 7 | Prairie County Justice Court | 2,442 | 946 | 38.7% |

| 7 | Richland County Justice Court | 7,658 | 5,503 | 71.9% |

| 7 | Wibaux County Justice Court | 1,908 | 1,631 | 85.5% |

| 8 | Cascade County Justice Court | 29,089 | 24,104 | 82.9% |

| 9 | Glacier County Justice Court | 5,091 | 3,054 | 60.0% |

| 9 | Pondera County Justice Court | 5,791 | 4,758 | 82.2% |

| 9 | Teton County Justice Court | 2,103 | 1,354 | 64.4% |

| 9 | Toole County Justice Court | 6,389 | 4,091 | 64.0% |

| 10 | Fergus County Justice Court | 6,051 | 4,109 | 67.9% |

| 10 | Judith Basin County Justice Court | 3,946 | 2,191 | 55.5% |

| 10 | Petroleum County Justice Court | 391 | 295 | 75.4% |

| 11 | Flathead County Justice Court | 40,268 | 31,843 | 79.1% |

| 12 | Chouteau County Justice Court | 5,198 | 4,775 | 91.9% |

| 12 | Hill County Justice Court of Record | 11,107 | 5,709 | 51.4% |

| 12 | Liberty County Justice Court | 1,342 | 635 | 47.3% |

| 13 | Yellowstone County Justice Court | 49,856 | 43,945 | 88.1% |

| 14 | Golden Valley County Justice Court | 1,377 | 544 | 39.5% |

| 14 | Meagher County Justice Court | 1,417 | 986 | 69.6% |

| 14 | Musselshell County Justice Court | 3,556 | 2,050 | 57.6% |

| 14 | Wheatland County Justice Court | 2,858 | 1,745 | 61.1% |

| 15 | Daniels County Justice Court | 858 | 680 | 79.3% |

| 15 | Roosevelt County Justice Court 1 | 1,655 | 1,313 | 79.3% |

| 15 | Roosevelt County Justice Court 2 | 2,852 | 2,347 | 82.3% |

| 15 | Sheridan County Justice Court | 1,928 | 1,129 | 58.6% |

| 16 | Carter County Justice Court | 2,148 | 1,787 | 83.2% |

| 16 | Custer County Justice Court | 14,866 | 13,898 | 93.5% |

| 16 | Fallon County Justice Court | 1,168 | 856 | 73.3% |

| 16 | Garfield County Justice Court | 2,205 | 864 | 39.2% |

| 16 | Powder River County Justice Court | 5,937 | 4,578 | 77.1% |

| 16 | Rosebud County Justice Court, Dept. 1 | 8,203 | 5,740 | 70.0% |

| 16 | Treasure County Justice Court | 1,068 | 710 | 66.5% |

| 17 | Blaine County Justice Court | 3,232 | 2,452 | 75.9% |

| 17 | Phillips County Justice Court | 3,358 | 2,523 | 75.1% |

| 17 | Valley County Justice Court | 4,978 | 3,282 | 65.9% |

| 18 | Gallatin County Justice Court | 35,476 | 26,013 | 73.3% |

| 19 | Lincoln County Justice Court | 10,297 | 9,341 | 90.7% |

| 20 | Lake County Justice Court | 11,210 | 7,858 | 70.1% |

| 20 | Sanders County Justice Court | 7,980 | 6,288 | 78.8% |

| 21 | Ravalli County Justice Court | 21,615 | 18,472 | 85.5% |

| 22 | Carbon County Justice Court | 5,693 | 3,964 | 69.6% |

| 22 | Stillwater County Justice Court | 7,135 | 4,162 | 58.3% |

Number of Cases Filed in City Courts with Race Information Available, 2015–2020

| Judicial District | Court | Cases Filed | Cases with Race | % Cases with Race |

| 1 | East Helena City Court | 1,614 | 2 | 0.1% |

| 1 | Townsend City Court | 1,037 | 2 | 0.2% |

| 2 | Butte City Court | 19,250 | 6,184 | 32.1% |

| 3 | Deer Lodge City Court | 1,801 | 19 | 1.1% |

| 3 | Phillipsburg City Court | 19 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 4 | Alberton City Court | 77 | 4 | 5.2% |

| 4 | Town Court of Superior | 173 | 2 | 1.2% |

| 5 | Boulder City Court | 637 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 5 | Dillon City Court | 2,526 | 66 | 2.6% |

| 5 | Ennis City Court | 1,334 | 1 | 0.1% |

| 6 | Big Timber City Court | 553 | 10 | 1.8% |

| 6 | Hardin City Court | 4,176 | 1,906 | 45.6% |

| 6 | Livingston City Court | 3,205 | 22 | 0.7% |

| 7 | Fairview City Court | 3,671 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 7 | Glendive City Court | 4,683 | 3,790 | 80.9% |

| 7 | Sidney City Court | 6,909 | 4,252 | 61.5% |

| 7 | Terry City Court | 89 | 15 | 16.9% |

| 7 | Wibaux City Court | 66 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 8 | Belt City Court | 29 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 8 | Cascade City Court | 217 | 18 | 8.3% |

| 9 | Conrad City Court | 614 | 292 | 47.6% |

| 9 | Cut Bank City Court | 2,256 | 319 | 14.1% |

| 9 | Fairfield City Court | 700 | 1 | 0.1% |

| 9 | Shelby City Court | 1,222 | 18 | 1.5% |

| 10 | Lewistown City Court | 3,805 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 11 | Columbia Falls City Court of Record | 7,639 | 7,385 | 96.7% |

| 12 | Havre City Court | 9,617 | 157 | 1.6% |

| 13 | Laurel City Court | 4,124 | 674 | 16.3% |

| 14 | Harlowton City Court | 638 | 4 | 0.6% |

| 14 | Roundup City Court | 1,273 | 12 | 0.9% |

| 14 | White Sulphur Springs City Court | 324 | 6 | 1.9% |

| 15 | Culbertson City Court | 176 | 17 | 9.7% |

| 15 | Scobey City Court | 210 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 15 | Wolf Point City Court | 420 | 36 | 8.6% |

| 16 | Baker City Court | 490 | 335 | 68.4% |

| 16 | Broadus City Court | 9 | 6 | 66.7% |

| 16 | Colstrip City Court | 1,195 | 735 | 61.5% |

| 16 | Forsyth City Court | 529 | 6 | 1.1% |

| 16 | Hysham City Court | 16 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 16 | Miles City City Court | 5,518 | 23 | 0.4% |

| 17 | Chinook City Court | 629 | 5 | 0.8% |

| 17 | Glasgow City Court | 1,906 | 1,777 | 93.2% |

| 17 | Harlem City Court | 372 | 61 | 16.4% |

| 17 | Malta City Court | 517 | 139 | 26.9% |

| 18 | Belgrade City Court | 7,364 | 1,178 | 16.0% |

| 18 | Manhattan City Court | 1,093 | 2 | 0.2% |

| 18 | Three Forks City Court | 95 | 2 | 2.1% |

| 18 | West Yellowstone City Court | 3,704 | 40 | 1.1% |

| 19 | Eureka City Court | 912 | 657 | 72.0% |

| 19 | Libby City Court | 1,583 | 1,067 | 67.4% |

| 19 | Troy City Court | 715 | 36 | 5.0% |

| 20 | Hot Springs City Court | 394 | 20 | 5.1% |

| 20 | Plains City Court | 791 | 70 | 8.8% |

| 20 | Polson City Court | 2,386 | 2,060 | 86.3% |

| 20 | Ronan City Court | 1,705 | 1,448 | 84.9% |

| 20 | St. Ignatius City Court | 1,320 | 0 | 0.0% |

| 20 | Thompson Falls City Court | 1,598 | 1,283 | 80.3% |

| 21 | Darby City Court | 600 | 35 | 5.8% |

| 21 | Hamilton City Court | 7,654 | 91 | 1.2% |

| 21 | Stevensville City Court | 505 | 198 | 39.2% |

| 22 | Bridger City Court | 3,094 | 7 | 0.2% |

| 22 | Columbus City Court | 1,298 | 3 | 0.2% |

| 22 | Fromberg City Court | 197 | 3 | 1.5% |

| 22 | Joliet City Court | 124 | 1 | 0.8% |

| 22 | Red Lodge City Court | 2,442 | 763 | 31.2% |

Number of Cases Filed in Municipal Courts with Race Information Available, 2015–2020

| Judicial District | Court | Cases with Race | % Cases with Race |

| 1 | Helena Municipal Court | 22,240 | 98.3% |

| 4 | Missoula Municipal Court | 60,532 | 94.1% |

| 8 | Great Falls Municipal Court | 48,083 | 95.4% |

| 11 | Kalispell Municipal Court | 6,825 | 31.8% |

| 11 | Whitefish Municipal Court | 9,573 | 49.6% |

| 13 | Billings Municipal Court | 69,761 | 94.3% |

| 18 | Bozeman Municipal Court | 17,125 | 59.6% |

Number of Cases Filed with Race Information Available by Judicial District, 2015–2020

| Judicial District | Cases Filed | Cases with Race | % Cases with Race |

| 1 | 63,443 | 49,752 | 78.4% |

| 2 | 35,714 | 8,540 | 23.9% |

| 3 | 29,254 | 18,275 | 62.5% |

| 4 | 120,080 | 102,702 | 85.5% |

| 5 | 29,894 | 17,102 | 57.2% |

| 6 | 30,022 | 16,914 | 56.3% |

| 7 | 39,411 | 22,916 | 58.1% |

| 8 | 84,458 | 75,449 | 89.3% |

| 9 | 25,067 | 14,381 | 57.4% |

| 10 | 14,734 | 6,887 | 46.7% |

| 11 | 91,789 | 55,937 | 60.9% |

| 12 | 28,288 | 11,445 | 40.5% |

| 13 | 136,915 | 116,551 | 85.1% |

| 14 | 11,807 | 5,362 | 45.4% |

| 15 | 8,480 | 5,672 | 66.9% |

| 16 | 44,411 | 29,986 | 67.5% |

| 17 | 15,521 | 10,443 | 67.3% |

| 18 | 79,465 | 44,369 | 55.8% |

| 19 | 14,313 | 11,704 | 81.8% |

| 20 | 30,200 | 19,028 | 63.0% |

| 21 | 31,841 | 18,929 | 59.4% |

| 22 | 21,256 | 9,335 | 43.9% |

Endnotes

1. The Council of State Governments Justice Center, Justice Reinvestment in Montana: Report to the Montana Commission on Sentencing (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2017).

2. Sara Bastomski et al., Racial Equity in Montana’s Criminal Justice System: An Analysis of Court, Corrections, and Community Supervision Systems (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2022).

3. “FullCourt Enterprise Progress Report,” Montana Supreme Court, Office of the Court Administrator, September 2020, https://courts.mt.gov/external/fullcourt/newsletter/sept2020.pdf.

4. Bastomski et al., Racial Equity in Montana’s Criminal Justice System: An Analysis of Court, Corrections, and Community Supervision Systems.

5. “District Courts,” Montana Judicial Branch, accessed December 20, 2021, https://courts.mt.gov/Courts/dcourt.

6. Ibid.

7. “Courts of Limited Jurisdiction,” Montana Judicial Branch, accessed December 20, 2021, https://courts.mt.gov/Courts/lcourt.

8. The Council of State Governments Justice Center interview and email correspondence with Judge Audrey Barger, Hill County Justice of the Peace, November 3, 2021, January 28, 2022, January 29, 2022, February 25, 2022.

9. “Criminal History Records Program Manual,” Montana Department of Justice, Criminal Records and Identification Services Section, accessed March 1, 2022, https://media.dojmt.gov/wp-content/uploads/CHRP-Manual-2016.pdf.

10. The Council of State Governments Justice Center interview with Shirley Faust, Missoula County Clerk of Court, October 28, 2021.

11. The Council of State Governments Justice Center interview with Angie Sparks, Lewis and Clark County Clerk of Court and Lisa Kallio, Lewis and Clark County Deputy Clerk and District Court Supervisor, February 24, 2022.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Montana Senate Bill 60, 65th Legislature, Regular Session (2017).

15. Montana Code Annotated, § 46-18-111 (2021).

16. Meeting between The Council of State Governments Justice Center and Montana Supreme Court, December 6, 2021.

17. “National Open Court Data Standards,” National Center for State Courts, accessed December 16, 2021, https://www.ncsc.org/services-and-experts/ areas-of-expertise/court-statistics/national-open-court-data-standards-nods.

18. “Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity,” U.S. Office of Management and Budget, October 30, 1997, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-1997-10-30/pdf/97-28653.pdf.

19. Kathryn Genthon and Diane Robinson, “Collecting Race & Ethnicity Data,” Court Statistics Project, October 18, 2021, https://www.ncsc.org/__data/ assets/pdf_file/0031/69691/Race_Ethnicity_Data_Collection_3.pdf.

20. David R. Williams, “Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status: Measurement and Methodological Issues,” International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation 26, no. 3 (1996): 483–505.

21. Lisa Mader, “Information Technology Strategic Plan,” Montana Judicial Branch, November 2020, https://courts.mt.gov/external/cao/docs/it-strategic-plan.pdf.

22. “Information Systems Audit: Integrated Justice Information Sharing (IJIS) Broker,” Montana Legislative Audit Committee, April 2017, https://leg.mt.gov/ content/Publications/Audit/Report/15DP-05.pdf.

23. Montana House Joint Resolution 31, 67th Legislature, Regular Session (2021), https://leg.mt.gov/bills/2021/billpdf/HJ0031.pdf.

24. “HJ 31: Criminal Justice System Data in Montana,” Montana State Legislature, accessed February 2, 2022, https://leg.mt.gov/committees/interim/ljic/studies-topics/hj31-ciminal-justice-system-data/.

25. “Resolution 1 In Support of Racial Equity and Justice for All,” Conference of Chief Justices and Conference of State Court Administrator, July 30, 2020, https://ccj.ncsc.org/__data/assets/pdf_file/0017/51191/Resolution-1-In- Support-of-Racial-Equality-and-Justice-for-All.pdf.

26. “Interactive Montana Crime Data,” Montana Board of Crime Control, accessed December 18, 2021, https://mbcc.mt.gov/Data/Montana-Reports.

27. Bastomski et al., Racial Equity in Montana’s Criminal Justice System: An Analysis of Court, Corrections, and Community Supervision Systems.

28. Ibid.

29. Ibid.

30. The Council of State Governments Justice Center email correspondence with Lisa Mader, Montana Judiciary Information Technology Director, January 14, 2022.

31. Bastomski et al., Racial Equity in Montana’s Criminal Justice System: An Analysis of Court, Corrections, and Community Supervision Systems.

Project Credits

Writing and Research: Matt Herman, MS*; Sara Bastomski, PhD*, CSG Justice Center

Advising: Alison Martin, PhD; Sara Friedman, MPA; Angela Gunter, MPA; Carl Reynolds, JD/MPA; Elizabeth K. Lyon; and Jessica Saunders, PhD, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Leslie Griffin, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Brenna Callahan, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Web Development: Catherine Allary, CSG Justice Center

*Equal contributors

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Grant No. 2019-ZB-BX-K002 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Data analyzed for this report were provided by the Montana Office of Court Administration. The findings and conclusions documented in this report are those of the authors and the CSG Justice Center and do not represent the views of Montana state government staff or associated stakeholders. The authors thank staff of the Montana Office of Court Administration for their support for this effort.

About the authors

Almost half of all violent crime in Kentucky is rooted in domestic violence (DV), and nearly 40 percent…

Read More Key Findings and Recommendations from Kentucky’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative to Better Understand and Address Domestic Violence

Key Findings and Recommendations from Kentucky’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative to Better Understand and Address Domestic Violence

Almost half of all violent crime in Kentucky is rooted in domestic violence (DV), and nearly 40 percent of people incarcerated in jails and prisons have a history of DV in their background.

Read More