Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics Can Address Mental Health and Substance Use Needs Across the Criminal Justice System Intercepts

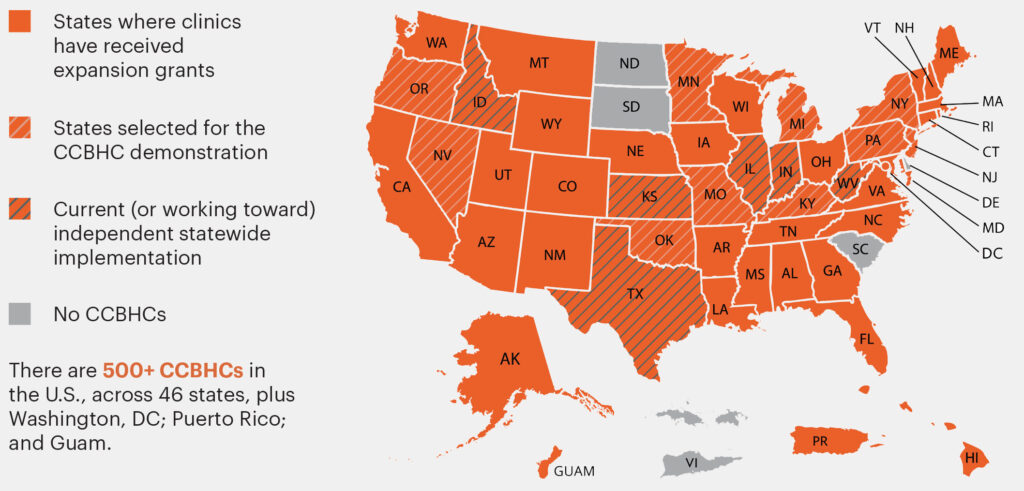

The Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic (CCBHC) model provides support to communities to help ensure that evidence-based care is available for people with mental health disorders or co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders who may be involved in the criminal justice system and to minimize incarceration and recidivism risks. There are currently more than 500 CCBHCs operating in 46 states, plus Washington, DC; Puerto Rico; and Guam. A growing number of states are moving to implement the model through a state plan amendment or Medicaid waiver, and individual community mental health and substance use services organizations continue to seek funding through Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration funded CCBHC Expansion Grants.

Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics Can Address Mental Health and Substance Use Needs Across the Criminal Justice System Intercepts

In 2020, 21 percent of American adults had a mental illness and 14.5 percent had a substance use disorder.1 However, almost half of people in state prisons that year (48 percent) had a mental illness, 26 percent had a substance use disorder, and 24 percent had co-occurring mental health and substance use treatment needs.2 Despite these stark numbers, correctional facilities often do not have adequate access to treatment and medications for people with these conditions.3 Additionally, because law enforcement officers frequently function as first responders to calls involving people with behavioral health needs, law enforcement agencies are incurring excessive costs related to emergency response without improved long-term outcomes.4

Many communities have successfully diverted people from the criminal justice system by helping them access low-barrier treatment in the community, such as through crisis hotlines, crisis centers, and community mental health clinics or substance use treatment providers. The Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic (CCBHC) model provides support to communities to help ensure that evidence-based care is available for people with mental health disorders or co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders who may be involved in the criminal justice system and to minimize incarceration and recidivism risks. The vast majority of CCBHCs and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) expansion grantees (96 percent) are actively engaged in one or more innovative activities in partnership with criminal justice agencies to improve outcomes for people in the justice system or those at risk of justice system involvement.5

CCBHCs Explained

A CCBHC is a specially designated clinic that provides a comprehensive range of mental health and substance use services through expanded care coordination with primary care providers, hospitals, social services, law enforcement, and other health services.6 The Excellence in Mental Health and Addiction Act demonstration (akin to a pilot) established a federal definition and criteria for CCBHCs.7 These criteria include standardized requirements for delivering high-quality care and the flexibility to tailor services to the individual needs of the communities they serve. CCBHCs must also serve all individuals who seek care, regardless of their ability to pay.8 Certification criteria also require partnerships between CCBHCs and law enforcement and juvenile and criminal justice agencies. Through these partnerships, CCBHCs provide health care staff, technology, and training to justice settings often at no cost to the justice partner.9

As not-for-profit organizations or units of a governmental behavioral health authority,10 CCBHCs may be funded via multiple streams:

- As of 2022, the CCBHC demonstration includes 10 states where state-certified CCBHCs receive a special Medicaid payment rate designed to cover the cost of expanding services to fully meet communities’ needs.

- CCBHC Expansion Grantees receive up to $4 million directly from SAMHSA to carry out the activities of a CCBHC but are not part of a statewide CCBHC initiative and do not receive an enhanced Medicaid payment rate.

- States have the option to independently implement CCBHCs statewide with Medicaid through a 1115 waiver or state plan amendment.11

Status of Participation in the CCBHC Model

CCBHCs as a Cornerstone for Crisis Response

All CCBHCs offer crisis response services as a core requirement of the model.12 At a minimum, these services include the following:

Prevention

- Early engagement in care

- Crisis prevention planning

- Outreach and support outside of clinic

Crisis Response

- 24/7 mobile teams

- Crisis stabilization

- Suicide prevention

- Detoxification

- Coordination with law enforcement and hospitals

Post-crisis Care

- Discharge/release planning

- Support and coordination

- Comprehensive outpatient MH/SU care

As of July 2022, the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (formerly known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline) became accessible via a three-digit dialing code (988). As call volumes continue to rise, requiring 988 call centers to link callers with urgent, on-the-ground support, CCBHCs’ mobile response and crisis stabilization abilities play an even more important role in crisis response.13 Ultimately, CCBHCs can help reduce police involvement in mental health and substance use crises and offer people services from professionals best equipped to provide crisis care.14

To date, individuals receiving services at CCBHCs:

- Have had 63.2 percent fewer emergency department visits;

- Spent 60.3 percent less time in jails;

- and Saw a 40.7 percent decrease in homelessness.15

CCBHCs and the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM)

The Sequential Intercept Model (SIM), developed by Policy Research Associates (PRA), is a conceptual means to inform community-based responses for supporting individuals with mental health and substance use needs within criminal justice systems. The National Center for State Courts has broadened this model to include justice system needs as well as the coinciding social needs of people with mental health and substance use conditions, such as food access and housing.16 Due to the comprehensive services they offer, CCBHCs can support justice system partners at each intercept of the SIM.17

- CCBHCs may be involved in mobile crisis response or co-response with law enforcement at the Community Services Intercept 0.

- At the Law Enforcement Intercept 1, CCBHCs may provide specialized training to officers on crisis intervention and behavioral health awareness to improve responses.

- During the Initial Detention/Initial Court Hearings Intercept 2, CCBHCs may be called upon to aid in pre-release screenings or serve as a referral source to ensure continuity of care upon release.

- In the Jails/Courts Intercept 3, CCBHCs may provide treatment to individuals involved in specialty courts (such as mental health courts, drug courts, veterans’ courts, etc.) or may provide specialized services to people who are incarcerated.

- At the Reentry Intercept 4, CCBHCs may again be involved in care coordination with community supervision, helping to ensure continuity of care for behavioral health services when individuals reenter the community after a period of incarceration.

- In the Community Corrections Intercept 5, CCBHCs can often be found as community-based behavioral health providers for individuals on probation or parole.

Ninety-five percent of CCBHCs18 are engaged in one or more collaborative practices with law enforcement and justice agencies.19

“Until July 25, 2022, all mobile crisis calls were responded to with police. Responses went to 979 in 2021 from 495 in 2020, a 98 percent increase that was unsustainable. Now, with additional resources and new protocols, teams consisting of peer support specialists and behavioral health therapists are responding without police as guided by the protocol. Already, we have reports of decreasing response times, and police are freed up to focus on criminal activity while maintaining the safety of the clinical staff.”

– Montgomery County, Maryland20

“Our system created, trains, and funds Mental Health Deputy Programs in partnership with local sheriff offices in 4 of our 8 counties improving our jail diversion rate from 23 percent to 71 percent over the last 4 years. [We] created a Diversion Center allowing for law enforcement to triage and drop off individuals experiencing mental health crises so the officer may return to the community, decreasing the average length of stay waiting in emergency departments from 39 hours to 2.5 hours.”

– Bluebonnet Trails Community Center, Texas21

Initiating a Partnership with CCBHCs

There are currently more than 500 CCBHCs operating in 46 states, plus Washington, DC; Puerto Rico; and Guam. A growing number of states are moving to implement the model through a state plan amendment or Medicaid waiver, and individual community mental health and substance use services organizations continue to seek funding through SAMHSA-funded CCBHC Expansion Grants. If you are interested in seeing how you can partner with a CCBHC in your community to serve the justice-involved population, find a CCBHC near you through the CCBHC locator.

Endnotes

1 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56) (Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, SAMHSA, 2021), https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf.

2 Tala Al-Rousan et al.,“Inside the nation’s largest mental health institution: A prevalence study in a state prison system,” BMC Public Health 17, no. 1 (2017): 342, https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-017-4257-0.

3 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings (HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJS) (Rockville, MD: National Policy Laboratory, SAMHSA, 2019), https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/pep19-matusecjs.pdf.

4 Treatment Advocacy Center, Road runners: The role and impact of law enforcement in transporting individuals with severe mental illness, A national survey (Arlington, VA: Treatment Advocacy Center, 2019), (Arlington, VA: Treatment Advocacy Center, 2019), https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/storage/documents/Road-Runners.pdf; Thomas S. Dee and Jaymes Pyne, “A community response approach to mental health and substance abuse crises reduced crime,” Science Advances 8 no. 23 (2022), https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abm2106.

5 National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2022 CCBHC Impact Report (Washington, DC, National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2020), https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2022-CCBHC-Impact-Report.pdf.

6 National Council for Mental Wellbeing, “How the CCBHC Model Helps Decriminalize Mental Illness,” December 16, 2020, YouTube video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wrtqTo1NIm8&t=42s; “What is a CCBHC?” National Council for Mental Wellbeing, accessed November 22, 2022, https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/program/ccbhc-success-center/ccbhc-overview/.

7 National Council for Mental Wellbeing, What is a CCBHC?, (Washington, DC, National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2020), https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/What_is_a_CCBHC_UPDATED_8-5-20.pdf.

8 “CCBHC Data and Impact,” The National Council for Mental Wellbeing, accessed June 26, 2023, https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/program/ccbhc-success-center/ccbhc-overview/ccbhc-data-impact/.

9 “CCBHC Data and Impact,” The National Council for Mental Wellbeing, accessed June 26, 2023, https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/program/ccbhc-success-center/ccbhc-overview/ccbhc-data-impact/.

10 National Council for Mental Wellbeing, What is a CCBHC? https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/What_is_a_CCBHC_UPDATED_8-5-20.pdf.

11 A 1115 waiver allows the Secretary of Health and Human Services to approve experimental, pilot or demonstration projects that are likely to help promote the goals of Medicaid (see https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/section-1115-demonstrations/about-section-1115-demonstrations/index.html). A Medicaid state plan details how a state runs its Medicaid program. When a state intends to change its Medicaid policies or approach, the state must submit a state plan amendment to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for approval (see https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid-state-plan-amendments/index.html).

12 “CCBHC Data and Impact,” The National Council for Mental Wellbeing, accessed June 26, 2023, https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/program/ccbhc-success-center/ccbhc-overview/ccbhc-data-impact/.

13 “988 Lifeline Performance Metrics,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), accessed January 1, 2023, https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/988/performance-metrics.

14 National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2022 CCBHC Impact Report, https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2022-CCBHC-Impact-Report.pdf.

15 “CCBHC Data and Impact,” The National Council for Mental Wellbeing, accessed June 26, 2023, https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/program/ccbhc-success-center/ccbhc-overview/ccbhc-data-impact/.

16 “Behavioral Health Resource Hub,” National Center for State Courts, accessed November 30, 2022, https://www.ncsc.org/behavioralhealth/resourcehub#top.

17 “CCBHC Data and Impact,” The National Council for Mental Wellbeing, accessed June 26, 2023, https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/program/ccbhc-success-center/ccbhc-overview/ccbhc-data-impact/.

18 National Council for Mental Wellbeing, Transforming State Behavioral Health Systems: Findings from States on the Impact of CCBHC Implementation (Washington, DC, National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2022), https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Transforming-State-Behavioral-Health-Systems.pdf.

19 “CCBHC Data and Impact,” The National Council for Mental Wellbeing, accessed June 26, 2023, https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/program/ccbhc-success-center/ccbhc-overview/ccbhc-data-impact/.

20 National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 2022 CCBHC Impact Report, https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/2022-CCBHC-Impact-Report.pdf.

21 Ibid.

Writing: Alicia Kirley and Sarah Neil, National Council for Mental Wellbeing, and Hadley Fitzgerald and Dustin Bartley, CSG Justice Center

Research: Alicia Kirley and Sarah Neil, National Council for Mental Wellbeing, and Dustin Bartley, CSG Justice Center

Advising: Dr. Allison Upton, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Leslie Griffin, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Aisha Jamil, CSG Justice Center

Web Development: eleventy marketing group

This project was supported by Grant No. 2020-MO-BX-K001 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

19 states were recently granted permission by CMS to reimburse critical reentry services with Medicaid funding for up…

Read MoreNew Jersey, Utah, Virginia, and Washington discuss their different "Aligning Health and Safety" approaches and some of the challenges they’ve experienced.

Read More A “Once in a Generation Opportunity” to Improve Reentry for Nearly 2 Million People

A “Once in a Generation Opportunity” to Improve Reentry for Nearly 2 Million People

19 states were recently granted permission by CMS to reimburse critical reentry…

Read More Getting the Right Response When Every Crisis Is Different: 4 States Share Lessons on Building Coordinated Crisis Systems

Getting the Right Response When Every Crisis Is Different: 4 States Share Lessons on Building Coordinated Crisis Systems

New Jersey, Utah, Virginia, and Washington discuss their different "Aligning Health and Safety"…

Read More