Improving Domestic Violence Responses in Vermont

Improving Domestic Violence Responses in Vermont

For decades, Vermont has made a concerted effort to support victims, protect communities, and emphasize accountability in cases of domestic violence. However, domestic violence continues to be a persistent problem in the state. Vermont leaders received a competitive grant from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance in 2020 to utilize a Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) approach to address these challenges specific to domestic violence. Vermont then contracted with the CSG Justice Center to assess domestic violence responses and recommend improved policies and practices. This brief provides an overview of domestic violence trends in Vermont and how they are being addressed through JRI.

Background

For decades, Vermont has made a concerted effort to support victims, protect communities, and emphasize accountability in cases of domestic violence. Since 1986, the Vermont Network Against Domestic and Sexual Violence (Vermont Network) has advocated for systemic change on behalf of its member organizations providing domestic and sexual violence advocacy to survivors. However, domestic violence continues to be a persistent problem in Vermont.¹ Between 2010 and 2020, domestic violence crimes accounted for an increasing proportion of all felony cases and a consistent proportion of all misdemeanor cases.²

Additionally, domestic violence homicides, most often committed with a firearm, accounted for nearly half of the state’s murders during this time.³ Historical disinvestment in Vermont’s Domestic Violence Accountability Programs (DVAPs) has further challenged domestic violence responses, as DVAPs are the only certified programs for people who commit domestic violence in the state of Vermont. Ultimately, the full impact of domestic violence in the state remains unknown and is likely to be vastly underestimated. Limited data exist on victims and survivors who do not engage with the criminal justice system, and as thousands of Vermonters who have committed domestic violence move through court, correctional, and treatment systems each year, substantial challenges and gaps in data limit the full understanding of domestic violence prevalence. These challenges continue to threaten victim safety and limit the ability of individuals, communities, and agencies to respond effectively to domestic violence.

In July 2020, an existing Vermont Justice Reinvestment II Working Group responded to the state’s concerning domestic violence trends by recommending that the state examine and develop policies and practices related to domestic violence responses across the state.4 Vermont leaders—including Attorney General T. J. Donovan, Vermont Department of Corrections Interim Commissioner Jim Baker, the Department of Public Safety, and the Vermont Network—accordingly received a competitive grant from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) to utilize a Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) approach to address these challenges specific to domestic violence. Vermont then contracted with The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center to assess domestic violence responses and recommend improved policies and practices. All data findings and recommendations will be presented to an established Executive Working Group composed of Vermont leaders whose work directly connects with domestic violence.

Emphasizing coordinated community responses, this project encompasses a systemic approach to domestic violence reform in Vermont that aims to support victims and survivors within and outside of the criminal justice system while also underscoring accountability and examining resources for people who have committed domestic violence. CSG Justice Center staff, with guidance from the Vermont State Police, the Vermont Network, and other state agencies, are conducting a comprehensive analysis of data from domestic violence responses across Vermont. To create a more holistic picture of statewide domestic violence experiences and responses, CSG Justice Center staff are conducting focus groups and interviewing key stakeholders in Vermont’s domestic violence work, as well as analyzing quantitative data about domestic violence service provision and responses to people who have committed domestic violence. CSG Justice Center staff will seek to highlight disparities in policies, programs, and practices through both qualitative and quantitative data analyses. Analyses will explore differences in domestic violence prevalence across the state, service access and engagement, and intervention outcomes to underscore the vast range of victim and survivor experiences, which are often impacted by victims’ and survivors’ race, ethnicity, gender, sexual identity, economic and geographic differences, and other factors discovered in the analysis.

Based on the findings from these quantitative and qualitative analyses, research on established or emerging evidence-informed practices in the field of domestic violence, and input from CSG Justice Center experts, the established Executive Working Group will develop policy options that are designed to improve outcomes for victims and survivors, including those who do not typically seek formalized services, while also addressing the needs of people who commit domestic violence. These policy options will ultimately increase public safety by allowing the state to invest in strategies that can reduce domestic violence while improving and expanding domestic violence service provisions. Policy options may include formalized legislative efforts as well as localized community programmatic responses.

Domestic Violence Trends in Vermont

This overview highlights recent domestic violence trends in Vermont. Information presented here is based on Vermont statutes, publicly available reports from Vermont state agencies, or federal reports.

It is vital to underscore that data presented here represent only a part of the narrative about domestic violence experiences and responses in Vermont. Though indicative of larger trends, each statistic reflects the individual lives of the people who are impacted by domestic violence. Their stories are complex, unique, and extend far beyond a data point. In reviewing these numbers, it is also imperative to consider those individuals who have experienced and are experiencing domestic violence whose stories are not captured here. Those who are forgotten in outreach, who cannot or choose not to engage with formalized systems of support, or who have not identified that they are experiencing domestic violence continue to be impacted and must be recognized in future policy and practice innovations and reforms.

Although Vermont’s overall crime rate is one of the lowest in the nation,5 Vermont experiences substantial rates of domestic violence.6 However, limitations of publicly available data make the true prevalence of domestic violence unknown.

■ Many victims and survivors in Vermont remain unaccounted for. Prevalence estimates do not exist for domestic violence victims and survivors who do not seek services or engage the criminal justice system. If survivors seek services for domestic violence, it is usually after several assaults, rather than the first assault.7 Further, national survey data from 2015 reflect that in a sample of 637 women who were victims and survivors of domestic violence and utilized the National Domestic Violence Hotline’s services, more than half (51 percent) did not involve law enforcement. Issues such as fear of reprisal from a partner, treatment based on race or ethnicity, disability status, long-term negative consequences for their partner, and other issues may complicate an individual’s ability or desire to involve law enforcement.8

■ In recent years, Vermonters have consistently sought services related to domestic violence among the Vermont Network’s 15 member organizations. In 2021, the Vermont Network served nearly 7,430 people with issues related to housing, legal services, parenting supports, health care, economic or employment issues, and other advocacy services.9

■ Survey data from 2017 reveal that 20 percent of adult women and 8 percent of adult men in Vermont reported that an intimate partner had ever physically hurt, threatened, or used controlling behavior with them, with respondents aged 18 to 44 reporting the highest rates of physical abuse.10

■ Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals in Vermont were twice as likely as their non-LGBT peers (29 percent versus 13 percent) to report that an intimate partner had ever threatened them or made them feel unsafe. This is particularly concerning, as national data reflect that individuals identifying as LGBT report facing increased barriers to accessing services, such as perceived stigma, low levels of confidence in LGBT-specific services, and problematic treatment by service providers, all of which can contribute to underreporting and deter help-seeking.11

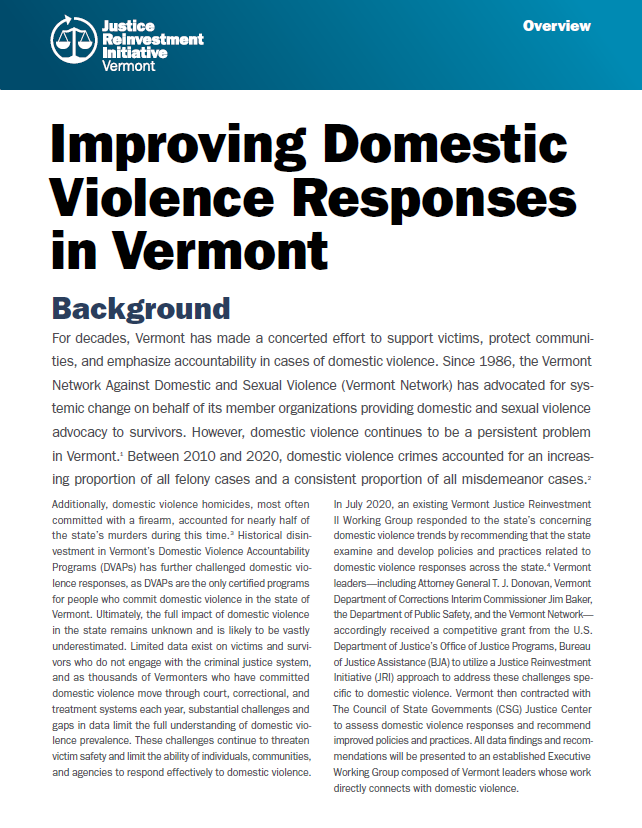

■ Data on the consequences of domestic violence, though limited in scope, are stark. Survey data collected between 2010 and 2012 reflect negative impacts of domestic violence faced by women in Vermont. Among women who had experienced domestic violence by an intimate partner and reported at least one negative impact, over half (51.5 percent) reported PTSD symptoms, 61.3 percent reported being fearful or concerned for their safety, 39.6 percent reported an injury, and more than a fifth (21.4 percent) needed medical care (see Figure 1).12

■ Domestic violence victims and survivors often experience intersecting forms of violence and abuse. Survey data from the National Violence Against Women Study reveal that 24.4 percent of women experiencing domestic violence reported sexual victimization, and 47.8 percent reported stalking.14 Human trafficking also remains a prominent concern in domestic violence cases, with human trafficking victims and survivors reporting experiences with domestic and sexual violence.15

■ Domestic violence also has implications for children; many families experiencing domestic violence interface with child welfare systems due to issues of potential abuse, maltreatment, or neglect. An estimated 57 percent of children who reported witnessing violence between intimate partners reported that they had experienced maltreatment, and children who experience or witness domestic violence are more likely to become involved in intimate partner violence in adolescence or adulthood, both as victims and those who commit violence.16

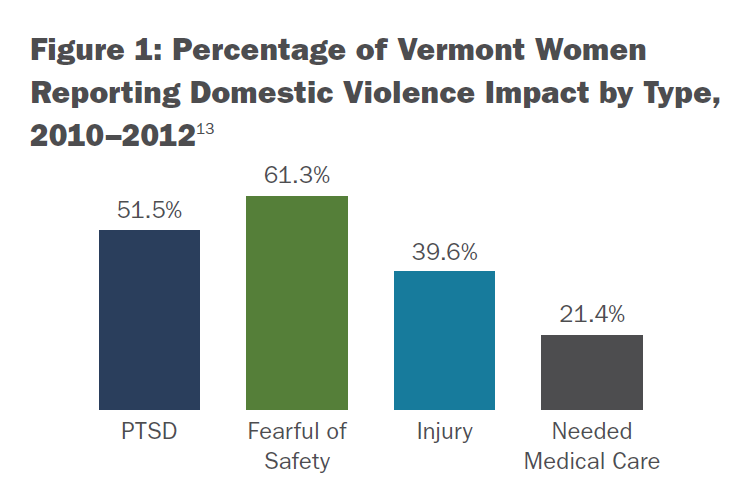

Domestic violence murders comprise nearly half of all homicides in the state, and most involve firearms.17

■ Between 2010 and 2020, 68 (45 percent) of Vermont’s 151 adult homicides were domestic violence related (see Figure 2).18

■ Most domestic violence homicides during this timeframe (56 percent) were committed with a firearm, and over half of homicide victims (56 percent) were murdered by a current or former intimate partner.19

■ The use of assessment or screening tools at the time of a domestic violence incident in Vermont is not standardized. More than 50 percent of law enforcement and nearly 30 percent of domestic violence advocates report that they are not familiar with domestic violence lethality assessments, which are used to gauge risk factors for serious injury and homicide.20

■ Minimal demographic information accompanies domestic violence homicide statistics, which limits the ability of service providers, organizations, and agencies to identify and reach populations who may be at an elevated risk of death.

Annually, thousands of individuals are arrested, incarcerated, or sentenced to community supervision for domestic violence crimes in Vermont.21

■ Among all of Vermont’s recorded crime in 2021, domestic assault was the second most common offense, with more than 560 charges filed. Additionally, violation of an abuse prevention order was the fifth most common offense, with more than 250 charges filed.22

■ In 2017, 389 people were incarcerated for at least one domestic violence-related offense. Of these individuals, 95 percent were men (371), 3 percent were women (13), and 2 percent (5) did not identify as male or female. Ninety percent of individuals (350) who were incarcerated for domestic violence offenses were held on felony charges.23

■ Most people charged with domestic violence offenses are on community supervision. In 2017, 77 percent of individuals convicted of a domestic violence offense in Vermont (1,298) were on probation or parole.24

■ Racial demographics are unclear for people charged and incarcerated for domestic violence offenses. However, general criminal justice system trends in Vermont reveal that Black individuals are disproportionately impacted by the criminal justice system and are more than six times as likely to be incarcerated as their White counterparts.25

■ The number of domestic violence survivors charged and/or incarcerated for domestic violence offenses in Vermont is unknown; however, it is estimated that 90 percent of women in Vermont’s justice system have experienced physical or sexual violence in their lifetimes.26

As misdemeanor and felony court cases overall have declined over the last decade, the proportion of felony domestic violence cases in Vermont courts has increased.27

■ Though overall felony cases decreased by 17 percent between 2010 and 2020, the proportion of domestic violence felonies steadily increased. In 2020, 494 total domestic violence cases accounted for 18 percent of all felonies and represented a 38 percent increase in domestic violence felony case filings from 2010.28

■ Domestic violence misdemeanors represented approximately 6 percent of all misdemeanor cases between 2016 and 2020. For example, in 2020, there were 9,946 misdemeanor cases, 628 (6 percent) of which were domestic violence related.30

■ In 2021, 3,393 relief from abuse orders were filed, representing a 9 percent increase in filings in the past year and since 2017.31

In addition to the human toll of domestic violence, the economic cost in Vermont is substantial.

■ Sexual violence and domestic violence in Vermont are estimated to cost the state at least $111 million each year in expenditures associated with health care, victims’ supports and services, law enforcement, the judiciary system, and the corrections system. Corrections expenditures account for more than half (52 percent) of these costs.32

■ Domestic violence is estimated to cost more than $5.4 million in lost wages across Vermont workplaces through absenteeism, diminished productivity, and job loss.33

Vermont’s rural geography poses challenges to domestic violence monitoring and is associated with barriers to service provision and accessibility.

■ Vermont is the most rural state in the nation with 61 percent of the population living in a county with fewer than 50,000 people.34

■ Survivors of domestic violence living in rural Vermont have identified a number of issues impacting their ability to seek help, such as geographic isolation, lack of transportation, social isolation, and perceptions of increased stigma against domestic violence victimization in rural communities.35

■ Issues of geographic and social isolation can compound existing structural issues that impact domestic violence. For example, Vermonters living in households with incomes below $25,000 report experiencing the highest lifetime rates of intimate partner violence of any income group, with nearly a quarter (24 percent) of such households reporting that an intimate partner has ever physically hurt them.36

■ The Vermont Network has distributed its services so that all residents are located within 30 miles of a domestic violence shelter; however, rural Vermonters who lack transportation still report access concerns. Survey data from 2019 illustrate that though there is an awareness of this service availability, geographic isolation is a barrier to service utilization for nearly half of the 33 survey respondents (48 percent).37

Though Vermont has historically innovated policies and practices related to domestic violence, disinvestment has been a challenge in recent years.

■ Bennington and Windham counties piloted domestic violence-specific courts in 2007 and 2013, respectively. An evaluation of the Bennington County Integrated Domestic Violence Project revealed successes in terms of recidivism and case processing speed. A lack of continued investment led to the end of both programs.38

■ In January 2015, every county had access to at least one certified DVAP, an intervention program for people who commit domestic violence. However, budget cuts eliminated the $50,000 statewide allocation for DVAP leading to the closure of several sites, including the state’s largest provider, and the elimination of the DVAP coordinator position.39

■ Recent investment in DVAP programs, in addition to support from the Center for Court Innovation, has helped spur the development of new DVAP value-based standards to guide the work of interventions for domestic violence. Current DVAP programming still faces challenges of availability, accessibility, and responsivity to the unique and varied needs of clients. Programs utilize a fee-for-service model and curriculum remains unstandardized.40

The Justice Reinvestment Initiative Approach

Step 1: Analyze data and develop policy recommendations

Using hundreds of thousands of individual state- and county-level records, CSG Justice Center staff, in collaboration with the Vermont Department of Public Safety and the Vermont Network, are conducting a comprehensive analysis of arrest patterns and behavioral health data as well as rates of domestic violence incidence, conviction, sentencing, probation, incarceration, parole, recidivism, and service provision.

Additionally, CSG Justice Center staff are examining structural issues, such as changes in DVAP funding; the design, delivery, and accessibility of programming for victims and people who commit domestic violence; and high rates of community supervision revocation to understand the capacity of current community-based domestic violence programming as well as gaps in service.

Analyses seek to highlight the experiences of victims and survivors who engage with the criminal justice system as well as those who do not in order to provide holistic, responsive recommendations. To gather cross-disciplinary perspectives and recommendations from individuals and communities across Vermont, CSG Justice Center staff are seeking input from stakeholders impacted by domestic violence. These stakeholders include victims and survivors, people who commit domestic violence, victim advocates, pretrial services and treatment providers, law enforcement, Tribal entities, court administrators, judges, prosecutors, defense counsel, corrections staff, and other individuals who engage with domestic violence work.

With the assistance of CSG Justice Center staff, the Executive Working Group will review the analyses and develop data-driven policy recommendations focused on reducing the incidence and prevalence of domestic violence in Vermont and increasing public safety. Policy recommendations will be available for the Executive Working Group’s consideration in fall 2022, and recommendations approved by the group will then be presented to the legislature. Recommendations for improved policies and practices will also be provided to organizations and agencies whose work involves issues of domestic violence.

Step 2: Adopt new policies and put reinvestment strategies into place

CSG Justice Center staff will partner with Vermont policymakers, organizations, and community members to adopt policy and practice recommendations to address domestic violence challenges. This will include implementing changes to existing policies and procedures as well as expanding innovative ideas and evidence-based strategies. Metrics for outcome measurement—emphasizing fidelity, accountability, and sustainability—will also be determined as policies are translated into practice. CSG Justice Center staff will develop implementation plans with state and local entities and provide stakeholders with frequent progress reports.

Step 3: Measure performance

CSG Justice Center staff will help state and local stakeholders in Vermont improve statewide data collection and information sharing. Partners will monitor internal changes, measure programmatic improvements, communicate implementation obstacles and opportunities, and share results. These efforts will increase Vermont’s capacity for making data-driven decisions on domestic violence policymaking, program provision, and budgeting while continuing to develop and strengthen collaborative working relationships within and among communities impacted by domestic violence.

Endnotes

1. Sharon G. Smith et al., The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010–2012 State Report (Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2017), https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs-statereportbook.pdf.

2. Vermont Judiciary, Appendix I Judiciary Statistics FY20 – Statewide (Montpelier: Vermont Judiciary, 2020), https://www.vermontjudiciary.org/sites/default/files/documents/FY%202020%20Appendix%20I%20-%20Statewide%20Data.pdf; Vermont Judiciary, Annual Report for FY2015 (Montpelier: Vermont Judiciary, 2015), https://www.vermontjudiciary.org/sites/default/files/documents/FY15_Statistical_Report.pdf.

3. Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission, Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission Report 2020 (Montpelier: State of Vermont, 2021), https://legislature.vermont.gov/assets/Legislative-Reports/2020-Final-DV-Report. pdf; Vermont Attorney General’s Office, State of Vermont Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission: 2018 Report (Montpelier: Vermont Attorney General’s Office, 2018), https://legislature.vermont.gov/assets/Legislative- Reports/2018-Final-domestic violence-Report.pdf.

4. The Council of State Governments Justice Center, Vermont Justice Reinvestment II Working Group Meeting, Third Presentation (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2019), https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/justice-reinvestment-in-vermont-third-presentation/. Data for 2015 were excluded from the CSG Justice Center NIBRS analysis due to a major reporting deficiency, so it is not included in these figures.

5. Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2019 Crime in the United States (Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2020), table 4, https://ucr. fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/tables/table-4.

6. Domestic violence is defined as the physical, sexual, and/or emotional maltreatment of one family member by another (APA 1996). Although the term domestic violence is often used interchangeably with the term intimate partner violence (IPV), domestic violence is a broader category. It typically includes all forms of family violence, such as elder abuse, child abuse, and IPV. IPV refers to acts of physical, sexual, and/or emotional aggression between intimate partners in particular (see https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/). From a legal standpoint, only certain forms of domestic violence or IPV are crimes (e.g., physical harms or threats). American Psychological Association, Violence and the Family: Report of the APA Presidential Task Force on Violence and the Family (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1996); The Council of State Governments Justice Center, Vermont Justice Reinvestment II Working Group Meeting, First Presentation (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2019), https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/VT-Launch-Presentation.pdf.

7. Laurie O. Robinson and Kristina Rose, “Practical Implications of Domestic Violence Research: For Law Enforcement, Prosecutors and Judges” (Washington D.C., U.S. Department of Justice, 2009).

8. T.K. Logan and Rob Valente, Who Will Help Me? Domestic Violence Survivors Speak Out About Law Enforcement Responses (Washington, DC: National Domestic Violence Hotline, 2015), https://www.thehotline.org/wp-content/ uploads/media/2020/09/NDVH-2015-Law-Enforcement-Survey-Report-2.pdf.

9. Vermont Network, 2021 Data Snapshot (Montpelier: Vermont Network Against Domestic and Sexual Violence, 2022), https://www.vtnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2021_NW_Data-Snapshot.pdf.

10. Vermont Department of Health, 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Survey (Burlington, VT: Division of Health Surveillance, 2018), https://www.healthvermont.gov/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/HSVR_BRFSS_2017.pdf.

11. Ibid.; April Pattavina et al., “Comparison of the Police Response to Heterosexual Versus Same-Sex Intimate Partner Violence,” Violence Against Women 13, no. 4 (2007): 374; Alesha Durfee, “Situational Ambiguity and Gendered Patterns of Arrest for Intimate Partner Violence,” Violence Against Women 18, 1 (2012): 64; Leigh Goodmark, “Transgender People, Intimate Partner Abuse, and the Legal System,” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 48 (2013): 151.

12. Sharon G. Smith et al., The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010–2012 State Report.

13. Ibid.

14. Lori Mann, Female Victims of Trafficking for Sexual Exploitation as Defendants: A Case Law (Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2020), https://www.unodc.org/documents/human-trafficking/2020/final_ Female_victims_of_trafficking_for_sexual_exploitation_as_defendants.pdf; Andrew R. Klein, Practical Implications of Current Domestic Violence Research: For Law Enforcement, Prosecutors, and Judges (Washington, DC:U.S. Department of Justice, 2009), https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/nij/225722.pdf.

15. Michele C. Black et al., The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: 2010 Summary Report (Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, 2011), https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs_report2010-a.pdf.

16. Child Welfare Information Gateway, Domestic Violence: A Primer for Child Welfare Professionals (Washington, DC: Domestic violence: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau, 2020), https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/domestic_violence.pdf; Sherry Hamby, David Finkelhor, Heather Turner, and Richard Ormrod, “The Overlap of Witnessing Partner Violence with Child Maltreatment and Other Victimizations in a Nationally Representative Survey of Youth,” Child Abuse and Neglect 34, no. 10, 734; “Domestic Violence and Child Abuse,” Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, accessed August 20, 2022, https://violence.chop.edu/domestic-violence-and-child-abuse.

17. Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission. Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission Report 2020.

18. Ibid.; Vermont Attorney General’s Office, State of Vermont Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission: 2018 Report.

19. Ibid.

20. Vermont Center for Crime Victim Services, STOP Formula Grant Implementation Plan for 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020, (Burlington: State of Vermont, 2017), https://www.ccvs.vermont.gov/uploads/2017-X1665- VT-WF%20STOP%20%20Implementation%20Plan%20FINAL%20COPY.pdf

21. “DOCPublicUseFile,” State of Vermont, accessed March 3, 2022, https://data.vermont.gov/d/vf3r-u4kv/visualization; Vermont Attorney General’s Office, State of Vermont Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission: 2018 Report.

22. “DOCPublicUseFile,” State of Vermont, accessed March 3, 2022, https://data.vermont.gov/d/vf3r-u4kv/visualization.

23. Vermont Attorney General’s Office, State of Vermont Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission: 2018 Report.

24. Ibid.

25. CSG Justice Center, “Results of the Racial Equity in Sentencing Analysis” (PowerPoint presentation, Justice Reinvestment Initiative in Vermont Presentation to Vermont Legislature, January 6, 2022).

26. ACLU Smart Justice, Blueprint for Smart Justice: Vermont (New York: American Civil Liberties Union, 2019), https://www.acluvt.org/sites/default/ files/wysiwyg/sj-blueprint-vt.pdf.

27. Vermont Judiciary, Appendix I Judiciary Statistics FY20 – Statewide; Vermont Judiciary, Annual Report for FY 2014 (Montpelier: Vermont Judiciary, 2014), http://mediad.publicbroadcasting.net/p/vpr/files/judiciary-statistics-vpr.pdf; Vermont Judiciary, Annual Report for FY2015 (Montpelier: Vermont Judiciary, 2015), https://www.vermontjudiciary.org/sites/default/files/documents/FY15_Statistical_Report.pdf.

28. Ibid.

29. Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission. Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission Report 2020; Vermont Attorney General’s Office, State of Vermont Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission: 2018 Report.

30. Ibid.

31. Vermont Judiciary, Annual Statistical Report FY21 (Montpelier: Vermont Judiciary, 2022), https://www.vermontjudiciary.org/sites/default/files/documents/FY2021%20Annual%20Statistical%20Report%20-%20FINAL.pdf.

32. Vermont Network, The Economic Impact of Domestic and Sexual Violence on the State of Vermont (Montpelier: Vermont Network Against Domestic and Sexual Violence, 2021), https://vtnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/ Economic-Impact-Report_4_2.pdf.

33. Michele Cranwell Schmidt and Autumn Barnett, Effects of Domestic Violence on the Workplace (Montpelier: Vermont Council on Domestic Violence, 2012), https://www.uvm.edu/sites/default/files/media/VTDV_ WorkplaceStudy2012_Presentation.pdf.

34. Corinne Peek-Asa et al., “Rural Disparity in Domestic Violence Prevalence and Access to Resources,” Journal of Women’s Health 29, no. 11 (2011): 1743; United States Census 2010, Vermont: 2010 Population and Housing Unit Counts (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration, 2012), https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/2010/cph-2/cph-2-47.pdf.

35. Rebecca Stone et al., “‘He Would Take My Shoes and All the Baby’s Warm Winter Gear so we Couldn’t Leave’: Barriers to Safety and Recovery Experienced by a Sample of Vermont Women with Partner Violence and Opioid Use Disorder Experiences,” The Journal of Rural Health 37 (2021): 35.

36. Vermont Department of Health, 2017 Behavioral Risk Factor Survey.

37. Vermont Center for Crime Victim Services, STOP Formula Grant Implementation Plan for 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020; Rebecca Stone et al., “‘He Would Take My Shoes and All the Baby’s Warm Winter Gear so We Couldn’t Leave’: Barriers to Safety and Recovery Experienced by a Sample of Vermont Women with Partner Violence and Opioid Use Disorder Experiences,” 35.

38. Amanda B. Cissner, Rebecca Thomforde Hauser, and Nida Abbasi, The Windham County Integrated Domestic Violence Docket: A Process Evaluation of Vermont’s Second Domestic Violence Court (New York: Center for Court Innovation, 2016), https://www.courtinnovation.org/sites/default/files/documents/DV_Vermont.pdf; Max Schleuter et al., Criminal Justice Consensus Cost- Benefit Working Group: Final Report (Northfield, VT: The Vermont Center for Justice Research, 2014), https://legislature.vermont.gov/Documents/2014/ WorkGroups/SIU%20Funding%20Study%20Committee/Results%20First%20 and%20Outcomes%20Evaluations%20of%20SIUs/W~Max%20Schlueter~Cost- Benefit%20Working%20Group%20-%20Final%20Report~10-8-2014.pdf.

39. Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission, Domestic Violence Fatality Review Commission Report 2016 (Montpelier: State of Vermont, 2017), https://vtnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/2016-Fatality-Review-Commission-Report.pdf.

40. “DVAP Standards,” Vermont Council on Domestic Violence, Accessed September 1, 2022. https://www.vtdvcouncil.org/dvap-standards.

This project was supported by Grant No. 2020-ZB-BX-0019 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

The statutory purpose of the Department of Public Safety is to promote the detection and prevention of crime, to participate in searches for lost and missing persons, and to assist in cases of statewide or local disasters or emergencies.

The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center is a national nonprofit organization that serves policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels from all branches of government. The CSG Justice Center’s work in justice reinvestment is done in partnership with The Pew Charitable Trusts and the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance. These efforts have provided data-driven analyses and policy options to policymakers in 26 states. For additional information about Justice Reinvestment, please visit csgjusticecenter.org/ projects/justice-reinvestment/.

The Vermont Network is Vermont’s leading voice on domestic and sexual violence. The Network is a statewide non-profit 501c3 membership organization which was founded in 1986. Our members are 15 independent, non-profit organizations which provide domestic and sexual violence advocacy to survivors of violence in Vermont.

Project Contact

Carly Murray, Senior Policy Analyst, cmurray@csg.org

Project Credits

Writing: Carly Murray, CSG Justice Center

Research: Sara Bastomski, Carly Murray, CSG Justice Center

Advising: Shundrea Trotty, David D’Amora, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Leslie Griffin, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Brenna Callahan, CSG Justice Center

Web Development: Catherine Allary, CSG Justice Center

About the author

Arkansas policymakers have long expressed concerns about the state’s high recidivism rate. Over the past 10 years, an…

Read MoreIn April 2025, Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed a package of bipartisan criminal justice legislation into law,…

Read More Explainer: Key Findings and Options from Arkansas’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative

Explainer: Key Findings and Options from Arkansas’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative

Arkansas policymakers have long expressed concerns about the state’s high recidivism rate.…

Read More Explainer: How a New Law in Arkansas Tackles Crime, Recidivism, and Community Supervision Challenges

Explainer: How a New Law in Arkansas Tackles Crime, Recidivism, and Community Supervision Challenges

In April 2025, Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed a package of…

Read More