Reducing the Number of People with Mental Illnesses in Jail

Six Questions County Leaders Need to Ask

Reducing the Number of People with Mental Illnesses in Jail

Stepping Up is a national initiative reducing overincarceration of people with mental illnesses. Stepping Up provides counties with a framework that allows each community to select the right evidence-based policies and practices for them, based on their data and unique local circumstances. This new edition of "Reducing the Number of People with Mental Illnesses in Jail: Six Questions County Leaders Need to Ask" advances the original Stepping Up framework published in 2017 by embedding a racial equity lens and uplifting the voices of people with lived experience. It provides six guiding questions for county leaders, offers tips gleaned from counties across the country that answered the call to action, and addresses ongoing challenges.

Introduction

Stepping Up is a national initiative reducing overincarceration of people with mental illnesses. When it launched in 2015, very few counties could pinpoint the number of people with behavioral health needs in their jails. County agencies generally operated in silos, and approaches to address mental illness in jails were piecemeal at best. And communities’ lack of data capacity limited their ability to identify high-impact strategies and track results.

Stepping Up has since grown from four inaugural counties to over 570. Nearly half of the U.S. population now lives in a Stepping Up county. In these counties, behavioral health and criminal justice professionals, county government officials, and community members are working toward a cross-systems, collaborative, data-informed approach to ensure that people receive the care they need to thrive in their communities, rather than jails, whenever possible. They are advancing the Stepping Up mission all while addressing pressing concerns such as the effects of COVID-19, renewed calls for racial equity, and the need to incorporate voices of lived experience in policy and practice development.

But one of the original challenges that spurred Stepping Up remains: jails across the country are still serving as de facto mental health care facilities. And the problem is bigger than jails. Over time, the Stepping Up partners—The Council of State Governments Justice Center, the National Association of Counties, and the American Psychiatric Association Foundation—have found that the size of the jail population with serious mental illnesses (SMI) often traces back to programs and policies beyond jail. Decisions at the time of a 911 or 988 crisis call about who to dispatch, if law enforcement is needed, and how to connect people to resources can all ultimately impact who ends up in jail. Similarly, at the other end of the system, probation supervision strategies that aren’t responsive to people with behavioral health needs can lead to further justice system involvement.

Stepping Up provides counties with a framework that allows each community to select the right evidence-based policies and practices for them, based on their data and unique local circumstances. This new edition of Reducing the Number of People with Mental Illnesses in Jail: Six Questions County Leaders Need to Ask enhances the original Stepping Up method, offers tips gleaned from counties across the country that answered the call to action, and addresses ongoing challenges.

The Six Questions Counties Need to Ask

The original “Six Questions”—the basis for the Stepping Up approach—remain relevant as a guiding framework for the initiative. County leaders have found that thoughtful consideration of each of these questions helps them determine to what extent their efforts will have a system-level impact.1

- Is our leadership committed?

- Do we conduct timely screening and assessments?

- Do we have baseline data?

- Have we conducted a comprehensive process analysis and inventory of services?

- Have we prioritized policy, practice, and funding improvements?

- Do we track progress?

1. Is Our Leadership Committed?

Reducing the number of adults with SMI and co-occurring substance use disorders (SUDs) in jails requires a cross-systems, collaborative approach involving a county-wide committee or planning team. This team should comprise members with diverse backgrounds and experiences, be representative of the larger community, and include people with lived experience in the criminal justice and behavioral health systems. The involvement of the public, especially local community-based organizations, is critical to ensure active commitment to the Stepping Up initiative and hold leaders accountable for addressing this important issue. Strong leadership, including the active involvement of people responsible for the county budget, is also essential to rally agencies reporting to a variety of independently elected officials. Designating a person to coordinate the planning team’s meetings and activities and manage behind-the-scenes details pushes the project forward.

What it looks like

- Mandate from leaders: The elected body representing the county (for example, the county commission) has established a clear mandate for behavioral health and criminal justice system administrators to implement systems-level reforms to reduce the number of people with SMI and co-occurring SUDs across the justice system. This mandate may take the form of a resolution2 or other formal commitment. County leaders may also use this opportunity to publicly declare the county’s dedication to addressing racial disparities and improving equitable access to diversion, services, and alternatives to justice system involvement.

- Representative planning team: The planning team comprises key leaders from the justice and behavioral health systems; representatives from the community, including organizations representing people with mental illnesses and their families; and representatives from county and municipal government. The planning team reflects the racial/ethnic diversity of the county and includes leaders from advocacy groups or other organizations that represent people with lived experience in the criminal justice and behavioral health systems. If a county has an existing criminal justice coordinating council or task force, the Stepping Up planning team acts as a standing sub-group or minimally reports to the coordinating council for endorsement of recommendations and action plans.

- Commitment to vision, mission, and guiding principles: The planning team is clear on the mandate and is committed to making the necessary system changes. Agreements, such as memoranda of understanding, are in place to formalize team function, document the initiative’s vision, mission, and guiding principles, and indicate the expectation that top decision-makers will attend planning meetings and implement changes that fall to their organization.

- Designated planning team chairperson: The chairperson is a county elected official or other senior-level policymaker who is in routine contact with leaders responsible for developing the county budget and administering the justice and behavioral health systems, and who can engage the stakeholders necessary to the success of the initiative. County leaders have charged the chairperson with holding agency administrators accountable for implementing the plan. These agency administrators are aware that the chairperson must provide routine updates to county leaders, often in an open forum, such as a commission meeting.

- Designated project coordinator: The planning team has assigned a project coordinator to work across system agencies to manage the planning process. The project coordinator—who might also be the county’s criminal justice coordinator—facilitates meetings, builds agendas, provides meeting minutes, and organizes subcommittee work as needed. The project coordinator also oversees research and data analysis, is in constant communication with planning team members, and has strong facilitation skills to establish a healthy team culture.

TIP FROM THE FIELD

Put Core Supports in Place

Counties that begin their work with the structure and support of a criminal justice coordinating council or like body have the clear advantage of having key decision-makers in place to oversee the project, review recommendations from the planning team, and endorse and commit to program and policy implementation. Coordinating councils that include a commissioner or county manager from the beginning are able to leverage that leader’s support when the time comes to make budget requests to the county government. Furthermore, a data scientist or analyst position can support the coordinator and the planning team with interpretating data and pinpointing impactful program and policy changes.

2. Do We Conduct Timely Screening and Assessments?

To reduce the number of people with SMI and co-occurring SUDs entering the justice system, counties first need to understand how prevalent these diagnoses are in their jail populations. This requires universally screening every person booked into jail for SMI and substance use. Without this foundational information, counties are ill-equipped to track whether they are reducing the number of people with behavioral health needs who are booked into jail and connecting them to the right interventions. Cross-analyzing this data with the racial makeup of the jail as compared to the community informs the planning process at a deeper level, assessing for “dual disproportionality”3 of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) individuals in the jail with SMI.

What it looks like

- Validated screening and assessment tools for serious mental illness and substance use: To ensure the accurate identification of the behavioral health needs of everyone booked into jail, the county has implemented validated screening tools and assessment processes.4 The Brief Jail Mental Health Screen and the Texas Christian University Drug Screen V (TCUDS V) are validated mental health and substance use screening tools that are available in the public domain, are easy and efficient to administer, and do not require specialized staff such as a sworn officer or a mental health professional to conduct.5 People who screen positive should receive a follow-up validated clinical assessment by a mental health professional to confirm a diagnosis.

TIP FROM THE FIELD

Adopt Existing Definitions

The Stepping Up initiative focuses on the population with SMI, as SMI is often defined by the state to determine eligibility for treatment and services funded by the state and denotes the population with the most acute mental health needs. Most Stepping Up counties have adopted the definition of SMI that aligns with their state’s definition, which often conforms to federal funding requirements as well. With a single, shared definition of SMI, Stepping Up counties can ensure that all systems are using the same measure to consistently identify and observe the population that is at the heart of the initiative’s efforts. Additionally, given the high number of people with a SMI who also have a co-occurring SUD, it is equally important to adopt a definition of SUD that can be used consistently across the systems participating in the project. Although there is no universal, standardized definition for SUD, planning teams can adopt a definition that draws upon established definitions from credible sources, such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, and the National Institute on Drug Abuse.6 The planning team should agree on consistent definitions for SMI and SUD, which may include SUDs that co-occur with mental illnesses. It is critical to be aware of the presence and severity of a SUD both to identify a clinical need and to address the condition as a risk factor for reoffending.

- Efficient screening and assessment process: Developing a screening and assessment process requires the planning team to determine the best party to conduct the screening. In some jurisdictions, jail personnel do the screening; in others, it is a contracted or embedded medical or behavioral health care provider. The logical time and place for screening for SMI and SUDs is at booking into the jail, and within this churning environment, quick and efficient processing is necessary. Because a person who screens positive for SMI may be released from jail before a full clinical assessment can be completed, a process is in place to connect them to a mental health care provider to complete the assessment process in the community.

- Additional screenings, assessments, and intake processes at the jail: At intake, the jail universally gathers race, ethnicity, and gender data via self-identification and screens for suicide risk. Other screenings that a jail may complete, depending on staff capacity and length of stay, include screening for trauma, traumatic brain injury, and pretrial risk of rearrest or failure to appear in court. It is recommended to assess an individual’s needs for housing and housing support services.7 As time allows, reentry planning staff may also use a post-conviction criminogenic risk assessment tool to estimate risk of reoffending to assist in determining diversion opportunities and developing community supervision plans.8

- Informed case planning: Once screenings and assessments are completed, the results inform collaborative case planning. The Criminogenic Risk and Behavioral Health Needs Framework is a tool to refer to when determining levels of supervision and behavioral health supports and treatment.

- Mechanisms for information sharing: The planning team has developed information-sharing agreements for agencies that protect individual privacy and support the need to share behavioral health information. Counties often create a flag process that serves as an indicator of the need to connect a person to services and to gather the necessary releases to enable discussing the case. A data match of all people booked into jail and the behavioral health system’s database identifies people who have previously received behavioral health care services and may require re-establishment of services.

TIP FROM THE FIELD

Embed Clinicians at the Jail to Support Information Sharing and Connections to Care

Clinicians who are embedded within jail facilities can play a key role in identifying people who have behavioral health needs. In some jails, the clinician may complete the screening and assessment process; in other jails, the screening may be completed at booking by jail personnel who refer people who screen positive for additional assessment to the clinical staff. Because embedded clinicians have access to the protected health information of the individual and can access the public information surrounding their legal case, they are in a position to fully know individuals’ needs and plan for improved outcomes. For example, clinicians can provide important behavioral health information to the court to help inform legal and treatment decisions. They can also provide evidence-based interventions through individual or group treatment while the person is in the facility to help them prepare for reentry.9 Employing an embedded clinician does not preclude counties from developing information-sharing policies and protocols necessary to facilitate system analysis and case management while adhering to professional codes of ethics and privacy law.

3. Do We Have Baseline Data?

The Stepping Up initiative recommends tracking the following four key measures:

- The number of people with serious mental illnesses booked into jail

- Their average length of stay

- The percentage of people connected to treatment

- Their recidivism rates

Baseline data on these measures highlights some of the best opportunities to reduce the number of people with SMI in the jail and provides benchmarks against which to gauge progress. With this information, county leaders can determine the impact of prevention and diversion strategies on bookings of people with SMI, the extent to which this population languishes in jail, whether there is continuity of care after release, whether investments in community-based treatment and supervision are reducing rearrest and reincarceration rates among people with SMI, and how subpopulations within the jail population with SMI fare.

What it looks like

- Baseline data on the general population in the jail: The jail collects baseline data for people with and without SMI to provide a point of comparison and determine whether disparities between these populations exist in bookings, lengths of stay, or recidivism rates.

- System-wide definition of recidivism: At the onset of planning, the planning team agrees on a definition of recidivism for consistent data tracking and reporting. As the overall goal of Stepping Up is to reduce the number of people with SMI in jails, participating counties generally define recidivism as a rebooking into jail. Agreeing on a definition of recidivism also requires setting a baseline rebooking rate for the population with and without SMI and determining intervals at which to measure recidivism.

- Electronic data collection: The jail electronically collects data on screening and assessment results to support ongoing analysis. Many Stepping Up counties have found it helpful to create a flag in the jail management system (JMS) when a person screens positive for SMI. This allows for efficient observation of this population across the Stepping Up four key measures and streamlines reporting. When information about the target population is entered in a data management system external to the JMS, such as a health provider system, it is necessary to develop a data-sharing process, which may include developing an integrated data management system. Whichever method the county adopts, the end goal is to have the capacity to capture and analyze key data effectively.

- Disaggregation by race, ethnicity, gender, and age: Further disaggregation of data by race, ethnicity, gender, and age takes place for the general jail population and the jail population with SMI. Compared with data on the demographics of the county at large, this analysis informs planning teams of disparities that may exist and discretionary decision points where bias may enter the criminal justice process. Using the self-identified race, ethnicity, and gender data collected at booking will help to ensure that baseline data accurately reflects the identities of people in jail.

- Routine reports from a county agency, state agency, or outside contractor: The planning team regularly issues a report containing information about the four key measures, along with potential policy recommendations. Baseline data should be generated with the understanding that this will be a report that is updated at least annually, using consistent definitions to track changes year to year. Counties with the capacity to develop a public dashboard can update their data online in real time.

TIP FROM THE FIELD

Incrementally Build Capacity to Track Data

Tracking data across the Stepping Up four key measures begins with “flagging” when a person screens positive for SMI and documenting that result electronically. From there, counties can build on their data-tracking capacity. Stepping Up counties often progress through the following levels of data-tracking capacity:

- Entering results of a positive screening for SMI into a dedicated field in the JMS.

- Downloading JMS data to track the Stepping Up four key measures, comparing the population with SMI to the general jail population.

- Setting targets and tracking progress following the Stepping Up Set, Measure, Achieve methodology and populating the corresponding progress survey.

- Using software to build real-time data dashboards, preferably shared on public websites.10 Justice Counts is an additional resource that equips states, jurisdictions, and agencies with dashboards and a suite of data tools to help drive decision-making.

4. Have We Conducted a Comprehensive Process Analysis and Inventory of Services?

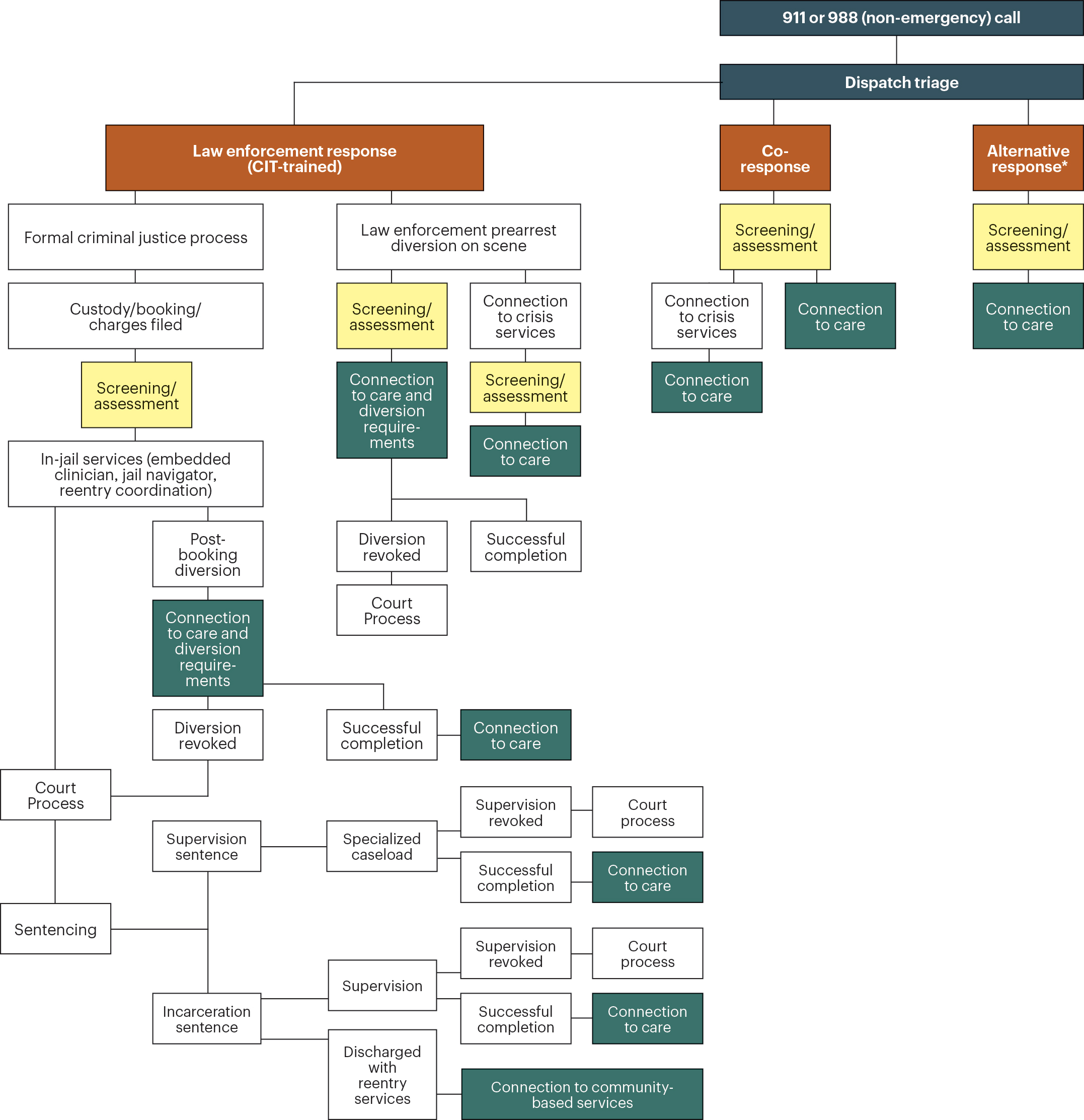

In every county, there are multiple opportunities to improve responses to people with behavioral health needs—like when a 911 or 988 call center receives a mental health call for service, when a person identified as having an SMI is booked into jail, or when defense counsel receives the results of that person’s mental health screening. A detailed, point-by-point system review helps county leaders determine where breakdowns in process occur, where improvements can be made, and where the supply of community-based services does not meet the demand. The planning team should apply a racial equity lens to each point in the system review to reduce the chance for bias and pinpoint opportunities to advance equity.

What it looks like

- Detailed process analysis: The planning team or a subcommittee traces each step of a response to a mental health call for service—whether the call is received by 911 or 988, whether the person was diverted to a behavioral health response or booked into jail, and the possible outcomes beyond diversion or booking. (See Figure 1 for a sample process chart of the possible paths a mental health call for service might take, including opportunities for connections to care and support.) At each decision point, the team asks questions such as the following:

- What are the steps involved in this decision-making process?

- Is the process timely and efficient?

- What information is collected at this point?

- How is that information shared and with whom?

- How is that information acted upon?

- Are the people involved in each decision point trained in their role?

- Do you have input—specifically from people who have gone through this process themselves—on how this decision point is working?

- Is this a discretionary decision-making point where one person or a small group of people hold the authority to determine a person’s trajectory in the justice system?

- Service capacity and gaps identified: The planning team identifies what options exist at each decision point, including crisis services, diversion opportunities, and community-based treatment, services, and supervision. The team also identifies what services are not available or exist but do not meet capacity needs. They may find that not enough services are engaging and culturally responsive to the local population or that they need to scale up evidence-based approaches that have been shown to meet the needs of people with mental illnesses and reduce the likelihood that they will commit a new offense.11

- Racial equity review: As part of the comprehensive process analysis and inventory of services, the planning team uses the following three-tier approach to pinpoint areas of opportunity to increase racial equity:

-

- Align policies, practices, and programs with baseline data by grouping them under one or more of the Stepping Up four key measures according to their potential impact on each measure.

- Identify and assess discretionary decision-making points in each program, policy, or practice. Planning teams should then assess how those decisions are made, by whom, and why, and brainstorm opportunities to address implicit bias, such as implementation of effective training.

- Apply a racial equity tool to policies, practices, and programs to conduct a deeper, structured analysis and center racial equity in evaluating how these policies, practices, and programs operate.12

TIP FROM THE FIELD

Use a Customized Racial Equity Tool

The Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) developed a racial equity tool specifically for government staff, elected officials, and other community-based organizations and provides supplementary worksheets.13 GARE recommends that communities begin by using the GARE Racial Equity Toolkit and subsequently customize based on experience and local needs.14 Some counties have developed their own racial equity tools that they use across local agencies, including justice and behavioral health.15

Figure 1. Responding to a Mental Health Call for Service

*Alternative response includes responses by specially trained emergency medical technicians, fire departments, mental health professionals, community responder teams,16 or peers as safety allows.

5. Have We Prioritized Policy, Practice, and Funding Improvements?

After completing a system analysis, the planning team then defines the most important policy, practice, and funding changes to help reduce the number of people in jails who have SMI. County leaders should provide guidance to the planning team on how to make policy recommendations and budget requests that are practical, concrete, and aligned with the fiscal realities and budget process of the county. For their part, the planning team should maintain regular communication with the people responsible for final decisions on program implementation (county commissioners and other officials, for example). The project coordinator ideally maintains this line of communication, covering key data, identification of gaps in services, opportunities to increase impact on the target population, and efforts to increase equity. Engaging high-level county decision-makers in the planning team’s ongoing efforts increases the likelihood that the recommended improvements will be received favorably. Encouraging community engagement and incorporating the voices of lived experience in prioritizing policy, practice, and funding improvements is critical to ensure that the planning team’s recommendations are reflective of the realities and needs of people in the community. Engaging community members in this process often provides an opportunity to supplement the quantitative justifications for a system improvement with anecdotal examples of real-word impact.

What it looks like

- Prioritized strategies: The planning team pursues strategies that address one or more of the Stepping Up four key measures.17 Drawing on the data collection process and system analysis described earlier, the planning team determines the most achievable ways of accomplishing one or more of these goals, with an emphasis on strategies that address systemic disparities and impact people with the most serious behavioral health needs who are also at the highest risk of reoffending.

TIP FROM THE FIELD

Apply a “One Step, One Policy” Approach to Advance Large-Scale Changes

Planning teams that are working to address racial inequities and other entrenched issues may feel overwhelmed if the results of their system analysis suggest the need for a complete system overhaul. Therefore, the Stepping Up partners recommend a “one step, one policy” approach. Identifying a specific policy or program change that has strong buy-in and demonstrable impact can result in initial successes to build on. This means breaking the work into manageable pieces and focusing on one policy, practice, or program at a time. The “one step, one policy” approach can not only enhance feasibility for planning teams, but also help in demonstrating commitment, change, and progress to stakeholders and communities.

- Detailed description of needs: Per county leaders’ guidance, the planning team submits a proposal to the county board related to its identified priorities. If necessary, the planning team’s proposal identifies the need for additional personnel, increased capacity for mental health and substance use treatment services and support services (such as housing and employment), and infrastructure improvements (such as information systems updates and training). All programming requests include evidence-based approaches that are carefully matched to the particular needs of the population. The proposal addresses personnel concerns such as staff placement and supervision, whether personnel are sworn or unsworn, whether mental health clinicians are behavioral health agency employees who are embedded in the jail or community supervision agencies, or if outsourcing to private providers is an appropriate option.

- Estimates/projections of the impact of new strategies: At a minimum, the plan projects the number of people to be served and explains to what extent new investments made will affect one or more of the Stepping Up four key measures. The proposed strategies include an impact analysis that describes the number of people to be served, the estimated improvement in services, and the projected benefits in terms of equitable access to treatment and services.

- Estimates/projections accounting for external funding streams: The plan describes to what extent external funding streams can be leveraged to fund new staff, treatment and services, and one-time and ongoing costs. Funding sustainability planning centers equity in the process. External funding sources may include:

- Federal program funding, including Medicaid, veterans benefits, and housing assistance

- State grants for mental health and substance use treatment services

- Federal and state discretionary grants

- Local philanthropic resources

- Description of gaps in funding best met through county investment: Per budget process guidelines, the planning team’s proposal should include specific suggestions for how county funds can meet a particular need or fill a gap that no other funding source can. The Strategy Lab provides guidance in determining the program and policy models that best suit a jurisdiction’s needs.

Figure 2. Aligning Strategies with the Four Key Measures

The table below demonstrates sample strategies that a county may prioritize to align under one or more of the Stepping Up four key measures. For each chosen strategy, counties should apply a racial equity tool, train personnel on implicit bias, and incorporate input from people with SMI who have experienced the justice system.

6. Do We Track Progress?

Once a county has completed the planning process and implemented the prioritized strategies, tracking progress and ongoing evaluation begin.18 The planning team must remain intact, and the project coordinator must continue to manage the implementation of the new strategies. Monitoring the completion of short-term, intermediate, and long-term goals is important, as it may take years to demonstrate measurable changes in prevalence rates. Showing evidence of more immediate accomplishments contributes to the momentum and commitment necessary to ensure that this is a permanent initiative. These near-term accomplishments may include hiring a permanent, dedicated project coordinator or data specialist, adding new types of crisis response such as a non-law enforcement community responder model or a co-responder model, or standing up a diversion or crisis stabilization center. First steps such as these can ultimately lead to reducing the number of people with SMI and co-occurring SUDs entering the justice system.

Tracking outcome data gives the planning team the justification necessary to secure continuation funding or additional implementation funding. Outcome data should be included in any budget requests to provide justification for continued or additional funding.

What it looks like

- Reporting timeline on four key measures: County leaders receive regular reports that include the data that is tracked, as well as progress updates on process improvement and program implementation. Members of the public also receive progress updates in a timely and accessible format. Counties with the data capacity may want to develop a dashboard for “real-time” reporting.

- Process for monitoring progress: The planning team continues to meet regularly to monitor progress on implementing the plan. The project coordinator remains the designated facilitator for this process and continues to coordinate subcommittees involved in the implementation of the policy, practice, and program changes, as well as to manage unforeseen challenges. In addition, the planning team remains abreast of developing research in the field and the introduction of new or improved evidence-based strategies for consideration.

- Ongoing evaluation of programming implementation: The evidenced-based programs adopted by the county are implemented with fidelity to the program model to ensure the highest likelihood that these interventions will achieve the anticipated outcomes. A fidelity checklist process ensures that all program certifications and requirements are maintained, and that ongoing training and skills coaching are provided to staff. Many counties establish a relationship with a local university to assist with research and evaluation, as well as with the validation of screening and assessment tools.

- Ongoing evaluation of programming for racial equity and responsivity to voices of lived experience: It is important to understand that well-planned program and policy implementation can have unintended consequences. Continuous review of data is necessary to ensure that programs and policies are equitable and that they benefit people whose racial and ethnic identities reflect the community. Involving voices of lived experience in decision-making should be organic and continuous. Ensure that people with firsthand experience in the criminal justice and behavioral health system continue to be represented on advisory committees and compensate them for their participation.

TIP FROM THE FIELD

Set Targets for Progress

The Stepping Up initiative issued a call to action in 2020 called Set, Measure, Achieve, which challenges counties to publicly set targets to demonstrate reductions in the jail population with SMI. By setting targets and measuring progress, counties can identify high-impact strategies to implement or expand to reach their goals. Having access to this data positions counties to prepare specific, data-driven requests for local, state, federal, and philanthropic support and justify the continuation of a program. More broadly, setting prevalence reduction targets will amplify counties’ transparency efforts and ensure coordinated cross-systems work toward common goals.

Conclusion

Since Stepping Up launched in 2015, counties across the country have established the rates at which people with SMI enter their justice system, identified program and policy improvements, and worked to prevent justice system involvement as appropriate and improve outcomes for people who do enter the system. The initiative continues to evolve and now includes intentional efforts to increase equity and incorporate voices of lived experience.

Stepping Up is guided by the counties doing this work every day. Stepping Up Innovators lead the way in applying the Stepping Up framework to build out a collaborative, comprehensive, cross-systems approach to reducing overincarceration of people with SMI. Innovator counties serve as mentors to communities at earlier stages in the process, learn and grow from engagement with their peers, and provide practical observations and advice that inform the direction of the national initiative. Peer learning opportunities are the bedrock of success for local Stepping Up efforts and the initiative. We encourage counties to apply the knowledge that has been gained and continue to learn from each other.

Find a host of additional resources on the Stepping Up website, join the initiative, request a connection with a Stepping Up Innovator county, and reach out to the Stepping Up partners for any additional information or support at steppingup@csg.org.

Endnotes

- For more on how counties have used this framework, see Alison E. Cuellar et al., “Drivers of County Engagement in Criminal Justice-Behavioral Health Initiatives,” Psychiatric Services 73, no. 6 (2022): 709–711. See also “Beating the Odds: How Counties Are Overcoming Barriers to Behavioral Health Service,” NACo Blog, June 26, 2023, accessed July 4, 2023, https://www.naco.org/blog/beating-odds-how-counties-are-overcoming-barriers-behavioral-health-service.

- Resolutions may need to follow the county’s prescribed template; alternatively, see the Stepping Up template.

- Bethany Joy Hedden et al., “Racial Disparities in Access to and Utilization of Jail- and Community-Based Mental Health Treatment in 8 U.S. Midwestern Jails in 2017,” American Journal of Public Health 111, no. 2 (2021): 277; Melissa Thompson, “Race, Gender, and the Social Construction of Mental Illness in the Criminal Justice System,” Sociological Perspectives 53, no. 1 (2010): 114–15.

- Validation of a screening tool requires completing a study based on data analysis to confirm if a tool is accurately screening for the need to conduct an additional assessment. Validation of a risk and needs assessment tool requires completing a study based on data analysis to confirm if a tool is predicting for the intended result (i.e., risk of reoffending), based on the characteristics of the population being assessed in the jurisdiction. As populations may change over time, it is important to validate this tool periodically. A properly validated tool should be predictively accurate across race and gender.

- For information about the Brief Jail Mental Health Screen, see http://www.prainc.com/?product=brief-jail-mental-health-screen. For information about the Texas University Drug Screen V, see http://ibr.tcu.edu/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/TCUDS-V-sg-v.Sept14.pdf. Stepping Up does not endorse the use of any specific tools; the Brief Jail Mental Health Screen and the Texas Christian University Drug Screen are examples of tools that are available for use without proprietary requirements.

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013); “Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, last updated June 9, 2023, https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/disorders; and “Addressing Drug Use and Addiction,” National Institute on Drug Abuse, June 2018, https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/understanding-drug-use-addiction.

- For more information on how corrections and reentry practitioners have partnered with housing providers to increase access to housing for people leaving prisons and jails, see Joey Hayashi and Thomas Coyne, “Breaking Down Barriers: Lessons from Housing and Justice System Collaborations,” The Council of State Governments Justice Center, March 27, 2023, https://csgjusticecenter.org/2023/03/27/breaking-down-barriers-lessons-from-housing-and-justice-system-collaborations/.

- For more information on how to conduct post-conviction risk and needs assessment in a way that prioritizes accuracy, fairness, transparency, and effectiveness, see the CSG Justice Center, Advancing Fairness and Transparency: National Guidelines for Post-Conviction Risk and Needs Assessment (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2022), https://projects.csgjusticecenter.org/risk-assessment/practitioners/.

- Adapted from Ethan Kelly and Andrea Chambers, Embedding Clinicians in the Criminal Justice System (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2022), https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/embedding-clinicians-in-the-criminal-justice-system/.

- See, for example, “Stepping Up Initiative Dashboard,” Douglas County, Kansas, accessed June 21, 2023, https://gis.douglascountyks.org/portal/apps/dashboards/f4a65d6ba1a3422caf3cfe1501c74284.

- For more on evidence-based approaches, see Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Best Practices for Successful Reentry From Criminal Justice Settings for People Living With Mental Health Conditions and/or Substance Use Disorders (Rockville, MD: National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory, 2023), https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/best-practices-successful-reentry-criminal-justice-settings-people-living-mental-health.

- For more on conducting this review, see Risë Haneberg and Kate Reed, Applying the Stepping Up Framework to Advance Racial Equity (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2023), 9–10.

- Julie Nelson and Lisa Brooks, Racial Equity Toolkit: An Opportunity to Operationalize Equity (New York: The Local and Regional Government Alliance on Race and Equity, 2015), https://www.racialequityalliance.org/ wp-content/uploads/2015/10/GARE-Racial_Equity_Toolkit.pdf.

- Nelson and Brooks, Racial Equity Toolkit, 5.

- See, for example, “Equity and Empowerment Lens,” Multnomah County Office of Diversity and Equity, accessed June 9, 2023, https://www.multco.us/diversity-equity/equity-and-empowerment-lens; “Racial Equity Toolkit,” Seattle Office for Civil Rights, accessed January 16, 2023, https://www.seattle. gov/civilrights/what-we-do/race-and-social-justice-initiative/racial-equity-toolkit; and Racial Equity & Social Justice Initiative, Racial Equity and Social Justice Tool: Process Guide (Madison, WI: City of Madison), https://www.cityofmadison.com/civil-rights/documents/RESJIprocessguide.pdf.

- For information on developing community responder programs, see “Expanding First Response: A Toolkit for Community Responder Programs,” The Council for State Governments Justice Center, December 2021, https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/expanding-first-response/.

- For more information on how Monterey County, for example, developed the county’s system map and identified opportunities to impact the Stepping Up four key measures, see Hallie Fader-Towe and Elizabeth Siggins, Stepping Up Monterey County System Mapping Project (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2021), https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/stepping-up-monterey-county-system-mapping-project/.

- For information on implementation strategies and examples, go to www.stepuptogether.org/toolkit.

Project Credits

The 2024 edition of this report was updated by Risë Haneberg, based on the original 2017 publication written by Risë Haneberg, Dr. Tony Fabelo, Dr. Fred Osher, and Michael Thompson. It was reviewed by the Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP), comprising eight individuals with lived experience in both the criminal justice and behavioral health systems. Feedback from the LEAP members was incorporated into this final document to ensure the content is fully inclusive of the voices of lived experience. We are grateful for their time and contributions to this work.

Writing: Risë Haneberg, CSG Justice Center

Reviewers: Lived Experience Advisory Panel; Dr. Tony Fabelo, Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute; Dr. Fred Osher; Michael Thompson, independent consultant

Editing: Katy Albis and Alice Oh, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Web Development: Yewande Ojo, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Aisha Jamil, CSG Justice Center

This project was supported by Grant No. 15PBJA-22-GK-03568-MENT awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

This project was also supported by the Jacob and Valeria Langeloth Foundation.

About the CSG Justice Center: The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center is a national nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that combines the power of a membership association, representing state officials in all three branches of government, with policy and research expertise to develop strategies that increase public safety and strengthen communities. For more information about the CSG Justice Center, visit www.csgjusticecenter.org.

About Stepping Up: Stepping Up is a national initiative reducing the overincarceration of people with mental illnesses and is a partnership between The Council of State Governments Justice Center, the National Association of Counties, and the American Psychiatric Association Foundation.

About the author

As the Stepping Up initiative marks its 10th year, America’s justice and behavioral health systems are facing a…

Read More19 states were recently granted permission by CMS to reimburse critical reentry services with Medicaid funding for up…

Read More"It is the humane, person-centered approach that supports and stabilizes individuals, their families, and their communities."

Read More The 10-Year Impact—and Future—of Stepping Up: Facing the Behavioral Health Crisis in Jails and Communities with Real Solutions

The 10-Year Impact—and Future—of Stepping Up: Facing the Behavioral Health Crisis in Jails and Communities with Real Solutions

As the Stepping Up initiative marks its 10th year, America’s justice and…

Read More A “Once in a Generation Opportunity” to Improve Reentry for Nearly 2 Million People

A “Once in a Generation Opportunity” to Improve Reentry for Nearly 2 Million People

19 states were recently granted permission by CMS to reimburse critical reentry…

Read More Local Criminal Justice System Innovations in Mental Health Services: Q&A with CSG Justice Center Advisory Board Member Dr. Doreen Williams

Local Criminal Justice System Innovations in Mental Health Services: Q&A with CSG Justice Center Advisory Board Member Dr. Doreen Williams

"It is the humane, person-centered approach that supports and stabilizes individuals, their…

Read More