States Supporting Familiar Faces Case Study: Georgia

Using Locally Driven State Policy to Stop the Revolving Door

States Supporting Familiar Faces Case Study—Georgia: Using Locally Driven State Policy to Stop the Revolving Door

Nationally, a small population of individuals frequently come into contact with law enforcement, jails, courts, crisis response, emergency departments, homeless services, and other behavioral health systems. These individuals, referred to as “familiar faces,” often have complex behavioral health needs that no single local system or program adequately addresses. From 2021 to 2023, the States Supporting Familiar Faces (SSFF) Project supported two states, Georgia and New Mexico, in reorienting funding and policies to strengthen local data-driven efforts to improve outcomes for familiar faces. This case study focuses on Georgia, while another case study covers the work in New Mexico, and a report synthesizes findings from both efforts.

In most states, a small population of people known as “familiar faces” has unmet behavioral health needs that cause them to have frequent contact with jails, courts, crisis response, and other behavioral health service systems. Repeated use of these services is not only costly but is often inconsistent and ineffective.

As a result, people who are familiar faces bounce from system to system without getting the care they need. From 2022 to 2023, the States Supporting Familiar Faces (SSFF) Project supported two states, Georgia and New Mexico, in reorienting funding and policies to strengthen local data-driven efforts to improve outcomes for familiar faces. The project was funded by Arnold Ventures and led by The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center. This case study focuses on Georgia, while another case study covers the work in New Mexico, and a report synthesizes findings from both efforts.

The experience and lessons learned in Georgia can be valuable for other states and local communities working on similar challenges. The most critical elements that allowed Georgia to move swiftly and effectively in policy areas with high complexity are as follows:

• Identifying effective champions within state agency leadership and engaged, multidisciplinary local teams

• Building a broad coalition of support to drive policy action

• Pinpointing locally informed policy and funding strategies that are impactful and technically and politically feasible

Behavioral Health and Justice Involvement in Georgia

Across the country, people with behavioral health needs often fall through the cracks of community support services and are overrepresented in local criminal justice systems. Nationally, approximately 20 percent of people in jails have a serious mental illness1 compared to about 4 percent of the general population.2 Georgia is no different. In one Georgia county, a 5-year study revealed that people with mental illness stayed in jail over 3 times as long as the jail population without mental illness, though further research is needed to understand why.3

These challenges are exacerbated by behavioral health workforce and supportive housing shortages. In 2021, Georgia ranked third for prevalence of mental illness in the population and 48th for access to care.4 Additionally, Georgia lost more than 28 percent of its affordable housing stock from 2011 to 2019, leading to a gap of more than 200,000 affordable units needed for extremely low-income renters.5 When people don’t get the care they need in the community or can’t find a stable, affordable place to live, they come to the attention of law enforcement and often wind up in jails and courthouses.

But there is immense opportunity in Georgia. The state’s expansive network of peer support specialists reaches even the most rural areas, and its system of crisis services is nationally recognized. Individual counties have been touted as national leaders at the intersection of criminal justice and behavioral health through initiatives like the Stepping Up initiative, the National Association of Counties’ Familiar Faces Initiative, and the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge. Indeed, there are many examples in Georgia of local policies and programs ripe for scaling at a state level or piloting in additional sites.

Georgia has 159 counties, including urban centers like Atlanta and Savannah and some of the most rural areas in America. There are 151 jails and 25 state-run regional behavioral health providers. Across this large, diverse system, state and local leaders are finding common ground in the ethical, financial, and practical need to improve responses for people living with serious mental illness in the state.

Familiar Faces in Georgia

Local data from across the state supports the need for policy and program changes to improve outcomes for people who are familiar faces in Georgia.

• Fulton County (Atlanta) used housing, behavioral health, and jail data matching to identify and analyze a pilot cohort of 100 people with high use of multiple systems. They found that people who are familiar faces are booked into local jails 10 times more frequently and use 20 times the number of jail bed days as the general jail population, costing $1.3 million annually in jail bed days alone.6

• Another study conducted by the Georgia Criminal Justice Coordinating Council looked at the people who had the most felony bookings (top 1 percent) across 9 diverse county jails in Georgia and found that people who are familiar faces were booked into jail, on average, 15 times over the 5-year period, or 3 times annually.7

With legislative and executive branch support, Georgia Supreme Court Chief Justice Michael Boggs requested technical assistance from the CSG Justice Center to support the efforts of Georgia’s Behavioral Health Reform and Innovation Commission in developing strategies to better serve people with behavioral health needs in Georgia, with a focus on familiar faces. In spring 2022, Georgia officially joined SSFF, committing to an 18-month long effort to create state and local policy strategies to address the needs of the state’s familiar faces.

Chief Justice Boggs chairs the Mental Health Courts and Corrections Subcommittee, which was created in statute under the Behavioral Health Reform and Innovation Commission. In 2022, the Familiar Faces Advisory Committee was created to advise the Mental Health Courts and Corrections Subcommittee on identifying state-level legislative and administrative interventions to improve outcomes for familiar faces. Chief Justice Boggs recruited champions from the legislature; Governor Brian Kemp’s Office; the judiciary; lead state agencies, including the Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD) and the Department of Community Affairs; other key Georgia organizations such as the Association of County Commissioners of Georgia; the Georgia Mental Health Consumer Network, a large convenor of certified peer specialists in the state; as well as local leaders from counties engaged in this work.

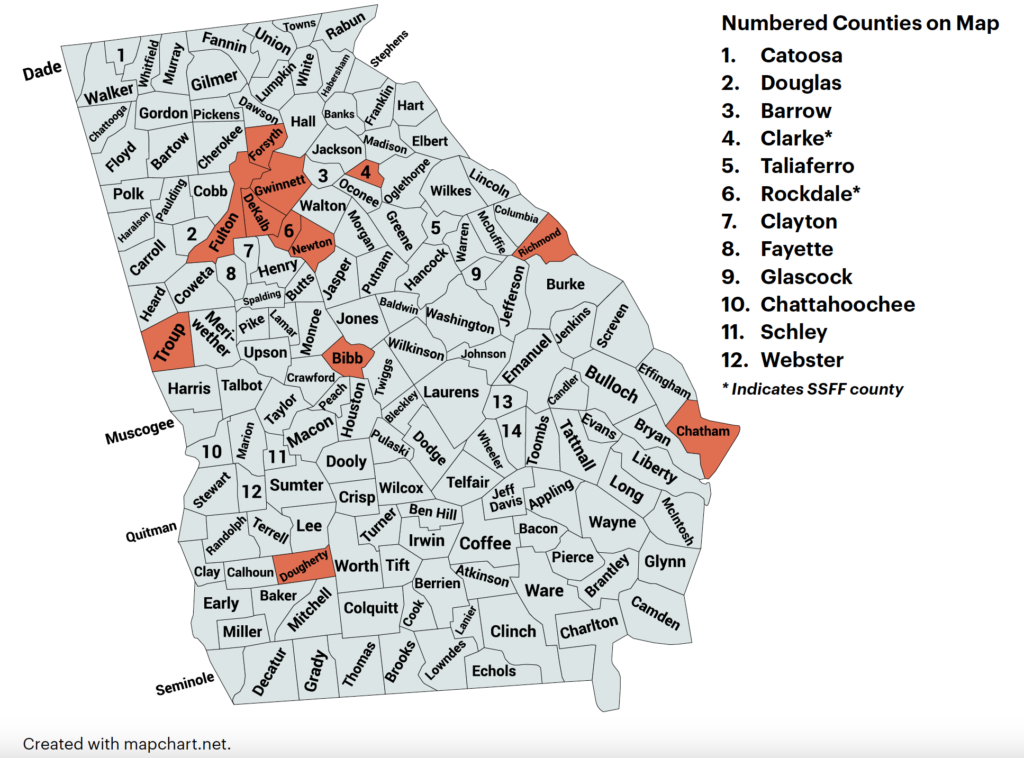

Coalition of Counties

Twelve counties in Georgia volunteered to work with their state counterparts to develop policy strategies. County representatives attended Familiar Faces Advisory Committee meetings to share information between local teams and the committee throughout the project. The CSG Justice Center hosted three virtual convenings over the course of the project with the county teams and held numerous meetings with individual county representatives to build the project’s state and local communication, planning, and collaboration infrastructure. The cohort of participating counties includes rural, suburban, and urban, as well as well-resourced and under-resourced communities from regions across the state.

Georgia States Supporting Familiar Faces Counties

Promising Practices that Came from Local Communities

Here are some examples of promising practices and programming that counties in Georgia are implementing. These practices informed the recommendations of the Familiar Faces Advisory Committee.

• Validated behavioral health screening in jails is essential for identifying who should be connected or reconnected to services and treatment. Georgia counties that have implemented best practice models include Chatham County, Fulton County, and Screven County.

• Jail in-reach programs, like the Gwinnett Reentry Intervention Project (GRIP), focus on people who are familiar faces by connecting the highest-need individuals leaving jail with community-based services. Between 2012 and 2017, recidivism rates for GRIP participants declined by 30 percent.8

• Georgia’s 26 state-funded crisis stabilization units (CSUs) provide 24/7 behavioral health services and evaluation to help divert people experiencing a mental health crisis from jail or hospital care and reduce public safety risk with early and effective services. Georgia’s CSUs show promising results. For example, in Chatham County, jail admissions for people with mental illness decreased by 33 percent following the opening of the CSU.9

• Another strategy in Georgia that has extremely strong evidence of effectiveness is drawing on the expertise of people with behavioral health and criminal justice services who are trained and certified as peer support specialists. These skilled professionals can relate to people who are returning home from jail while experiencing psychiatric symptoms and trying to seek out care, and they can help people with this often difficult transition. The state’s robust network of peer support specialists can intervene at critical points with people who are familiar faces to help them avoid hospitalization or arrest. In a study from Forsyth County, individuals who engaged with a peer support specialist had significantly fewer jail bookings following the connection than those who were not connected to peer support specialists, and those who did go to jail stayed for 26 percent fewer days than individuals who were not connected to peer support specialists (35 days vs. 26 days).10

Seeking Out Advisement from People with Lived Experience

The project drew on the expertise of Georgia’s well-established community of peer support practitioners and leaders for their advisement about policy priorities, barriers, and opportunities. A focus group composed of a geographically diverse group of peers, including people with direct experience in both behavioral health and corrections systems, met with CSG Justice Center staff in October 2023. Some of the findings from the focus group are as follows:

• While peers in Georgia have extensive experience working with local decision-makers to expand their reach within local jails and across systems, they identified expanding jail in-reach and coordination as a priority as people return to their communities.

• Peers can provide continuity of care at reentry when people return to geographically distant communities outside the service catchment area of jail reentry programs.

• Although there is extremely strong evidence for the effectiveness of peer supports11 and they are a vital part of a community behavioral health workforce, there are barriers to expanding peer support in the state, such as low wages and resistance to peer support workers by correctional staff and other key partners.

Identifying Policy and Funding Strategies to Improve Responses to Familiar Faces

Priorities Articulated by the Familiar Faces Advisory Committee

The Familiar Faces Advisory Committee met monthly between June 2022 and November 2022 to hear from the local teams and synthesize the information and data provided by state agency staff, focus groups, local best practices, and subject matter experts. The Advisory Committee prioritized the policies to include in its final recommendations based on their potential impact and their technical, political, and fiscal feasibility.

The Familiar Faces Advisory Committee prioritized the following challenges for policy action, including legislative, budgetary, or administrative action, because they saw opportunities for improvement with strategic state action:

• Severe behavioral health workforce shortages

• Behavioral health bed shortages (crisis, state hospital, supportive housing)

• Lack of capacity across systems and jurisdictions to share information between criminal justice and behavioral health providers

• Long wait times for evaluation and restoration of competency to stand trial

• Lack of access to housing for people who are familiar faces

• The need for best practice information for practitioners, such as a best practice clearinghouse

• The lack of a statewide definition of serious mental illness (SMI)

• The need for standardized metrics to collect, report on, and measure the impact of policy strategies selected for implementation

• Poor linkages between local jails and community services providers

This list of issues and challenges informed policy recommendations that the Advisory Committee developed and considered to improve outcomes for people who are familiar faces and local communities. Over the course of 3 meetings, the Advisory Committee prioritized 16 policies to include in its final set of recommendations. The Behavioral Health Reform and Innovation Commission received the Advisory Committee recommendations when it convened on November 16, 2022, and accepted them in full.

Supporting Implementation of Reforms and Scaling Successful Approaches

Nearly all the familiar faces policy recommendations moved quickly to implementation through legislation and administrative action in 2023; in some cases, implementation will extend into the 2024 legislative session. This rapid implementation relied on strong leadership in the DBHDD and the Department of Community Affairs as well as strategic use of multiyear initiatives.

The table below shows each policy recommendation and its implementation status as of the publication of this case study.

|

Policy Recommendation |

Implementation Status |

|

Expand access to various types of housing for familiar faces. |

The Department of Community Affairs (DCA) 2024 Low Income Housing Tax Credit Qualified Allocation Plan (QAP), published in August 2023, incorporates targeted changes to incentivize funding for housing development for familiar faces. DCA is also prioritizing housing developments for people with low incomes and/or who need supportive services. The final QAP was presented to the DCA Board for approval in October 2023. DCA is also implementing policies within its housing voucher programs to more effectively serve familiar faces by increasing the inventory of available units. Implementation of the two additional housing-related recommendations of the Advisory Committee is deferred for further consideration and development: (1) establishing tenant selection plans through DCA that do not create barriers to housing unrelated to fitness as a tenant, similar to approaches in North Carolina and Louisiana and (2) securing federal and private funding to seed a landlord incentive fund that would be allocated regionally to recruit more landlords serving familiar faces (such as leasing incentive payments and risk mitigation funds). |

|

Adopt statewide definitions of common terms, such as serious mental illness. |

An interagency working group led by DBHDD is identifying definitions of serious mental illness, homelessness, and familiar faces to be used across criminal justice and behavioral health agencies in the state to better facilitate information sharing. The definitions will be reviewed, finalized, and adopted by the Georgia Behavioral Health Coordinating Council by December 31, 2023. |

|

Implement standardized metrics to evaluate the impact of policy and service changes. |

DBHDD staff are finalizing several metrics for use in the jail in-reach pilot projects. The metrics are expected to be finalized by the end of 2023 and implemented in the pilot projects as they are stood up. The selection and use of metrics for the pilots will inform future policy, funding, and practice decisions as successful approaches are scaled up. The metrics in development include the following: • The number of people incarcerated who are familiar faces • The number of days between jail bookings for familiar faces • The number of days between arrests for familiar faces • The number of days in the community for familiar faces • A set of outcome performance measures of individuals’ experience of jail in-reach services (such as self-assessment of ability to manage care; knowledge about how to manage symptoms). These measures are expected to be completed and to begin being implemented in jail in-reach pilots by the end of 2023. DBHDD is also researching and developing measures of how well services are tailored to the individual clinical and social needs of people who are familiar faces, such as engagement in Assertive Community Treatment and other intensive community behavioral health services. |

|

Reform the state’s competency to stand trial process to improve outcomes for familiar faces who go through the process. |

DBHDD created a Forensic Competency Task Force to study and generate policy recommendations about processes, rules, and statutes regarding competency to stand trial and competency restoration. |

|

Improve coordination between jails and community service systems and implement validated, universal screening. |

DBHDD launched pilot jail in-reach programs in five county jails. Pilot funding began in July 2023 with a full-time certified peer mentor and case manager to facilitate connection to treatment services, housing vouchers, and other supportive housing, medical, and other benefits. Jail in-reach pilot sites implemented validated mental health and housing screening tools to identify people with behavioral health needs to link them to post-release care beginning in August 2023. Two of the Advisory Committee’s policy recommendations that required appropriations— (1) creating a county-based coordinator position to build collaboration between criminal justice and behavioral health partners and (2) increasing funding for Social Security Income/Social Security Disability Insurance Outreach, Access, and Recovery (SOAR) case managers and pilot programs in jails—are not currently being implemented. |

|

Address critical shortages in behavioral health services. |

DBHDD completed a statewide study of available crisis and other mental health treatment beds and a comprehensive workforce study in August 2023 to inform legislative recommendations in 2024 and multiyear capacity planning. DBHDD is working on several fronts to expand the use of certified peer support specialists, including hiring a state-level peer support specialist. |

|

Establish a best practice information clearinghouse. |

State leaders are developing innovative plans for establishing and funding a center for learning and knowledge sharing among peer communities in Georgia doing this work. |

Endnotes

1. E. F. Torrey et al., The Treatment of Persons with Mental Illness in Prisons and Jails: A State Survey (Arlington, VA: Treatment Advocacy Center, 2014).

2. “Mental Health Facts in America,” National Alliance on Mental Illness, accessed March 8, 2022, https://www.nami.org/nami/media/nami-media/infographics/generalmhfacts.pdf.

3. Stefanie L. Howard, Forsyth County Co-Responder Model: Descriptive and Process Evaluation (Atlanta: Criminal Justice Coordinating Council Statistical Analysis Center, 2022).

4. Maddy Reinert, Theresa Nguyen, and Danielle Fritze, The State of Mental Health in America: 2021 (Alexandria, VA: Mental Health America, Inc., 2020).

5. National Low Income Housing Coalition, The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Rental Homes (Washington, DC: National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2022), https://nlihc.org/gap; Joint Center for Housing Studies, America’s Rental Housing Market 2022 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 2022), https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/americas-rental-housing-2022

6. Tyler Technologies, Case Study: Fulton County’s System-Wide Jail Overhaul (Atlanta: Tyler Technologies, 2021).

7. Georgia Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, Analysis of Nine Jail Datasets for Representation of Mental Illness among Familiar Faces (Atlanta: Georgia Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, 2022).

8. Gwinnett County Sheriff’s Office, GRIP: Gwinnett Re-Entry Intervention Program, Reentry Report 2016 (Atlanta: Gwinnett County Sheriff’s Office, 2016).

9. Tara Jennings, “Chatham County, Georgia” (PowerPoint presentation, Georgia Familiar Faces Advisory Committee, virtual meeting, July 13, 2022).

10. Howard, Forsyth County Co-Responder Model.

11. Cecilie Høgh Egmose et. al. “The Effectiveness of Peer Support in Personal and Clinical Recovery: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Psychiatric Services 74, no. 8 (2023): 847–858, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202100138; Reham A. Hameed Shalaby and Vincent O Agyapong, “Peer Support in Mental Health: Literature Review,” JMIR Mental Health 7, no. 6 (2020), https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32357127/.

Project Credits

Writing: Amy Button, Marilyn Leake, CSG Justice Center

Research: Marilyn Leake, CSG Justice Center, Stefanie Lopez-Howard, Georgia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities

Advising: Hallie Fader-Towe, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Leslie Griffin, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Web Development: Yewande Ojo, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Kevin Dugan, CSG Justice Center

About the Authors

New Mexico launched a pilot program in 2024 to divert people with mental health needs and misdemeanor charges…

Read More From Courtroom to Care: 5 Key Strategies Behind New Mexico’s Competency Diversion Pilot

From Courtroom to Care: 5 Key Strategies Behind New Mexico’s Competency Diversion Pilot

New Mexico launched a pilot program in 2024 to divert people with mental health needs and misdemeanor charges out of the justice system and into care.

Read More