States Supporting Familiar Faces Case Study: New Mexico

Using Locally Driven State Policy to Stop the Revolving Door

States Supporting Familiar Faces Case Study—New Mexico: Using Locally Driven State Policy to Stop the Revolving Door

Nationally, a small population of individuals frequently come into contact with law enforcement, jails, courts, crisis response, emergency departments, homeless services, and other behavioral health systems. These individuals, referred to as “familiar faces,” often have complex behavioral health needs that no single local system or program adequately addresses. From 2021 to 2023, the States Supporting Familiar Faces (SSFF) Project supported two states, Georgia and New Mexico, in reorienting funding and policies to strengthen local data-driven efforts to improve outcomes for familiar faces. This case study focuses on New Mexico, while another case study covers the work in Georgia, and a report synthesizes findings from both efforts.

In most states, there is a small population of people known as “familiar faces” who have complex and unmet behavioral health needs that cause them to have frequent contact with jails, courts, crisis response, and other behavioral health service systems. Repeated use of these services is not only costly but is often inconsistent and ineffective. As a result, people who are familiar faces bounce from system to system without getting the care they need.

From 2022 to 2023, the States Supporting Familiar Faces (SSFF) Project supported two states, Georgia and New Mexico, in reorienting funding and policies to strengthen local data-driven efforts to improve outcomes for familiar faces. SSFF was funded by Arnold Ventures and led by The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center. This case study focuses on New Mexico, while another case study covers the work in Georgia, and a report synthesizes findings from both efforts.

The experience and lessons learned in New Mexico can be valuable for other states and local communities working on similar challenges. The most critical elements that allowed New Mexico to move swiftly and effectively in policy areas with high complexity are as follows:

• Identifying effective champions within state agency leadership and engaged, multidisciplinary local teams

• Building a broad coalition of support to drive policy action

• Pinpointing locally informed policy and funding strategies that are impactful and technically and politically feasible

Behavioral Health and Justice Involvement in New Mexico

Across the country, people with behavioral health needs often fall through the cracks of community support services and are overrepresented in local criminal justice systems. Nationally, approximately 20 percent of people in jails have a serious mental illness compared to about 4 percent of the general population.1 New Mexico is no different. One county in New Mexico created a monthly “priority population” list of people with multiple jail bookings within the past 18 months. In 2020, of the 216 individuals in the “priority population,” 69 percent had been assigned to the jail psychiatric unit, and 30 percent were identified as having a mental illness.2

In addition, New Mexico is facing a crisis in substance use and overdose deaths. Over 200,000 New Mexicans are living with substance use disorder (SUD),3 and New Mexico had the country’s sixth-highest drug overdose death rate and the highest rate of alcohol-related deaths in 2021.4 Despite the high rates of SUD and alcohol-related and drug overdose deaths, it is estimated that only about a third of people with SUD are receiving treatment in New Mexico.5

State and local leaders are working to develop responsive and innovative care systems, but expanding access to SUD treatment is challenging. New Mexico is geographically big with a dispersed population—there are only about 18 people per square mile—and is made up of very large rural counties.6 The challenge of building a statewide behavioral health system across a large, mostly rural, geography is exacerbated by severe behavioral health workforce and housing shortages.

State leaders in New Mexico have been working for years on identifying solutions at the intersection of behavioral health and criminal justice. Most recently, the New Mexico courts successfully obtained a federal Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program grant to work with counties on improving outcomes at this intersection. The Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC), with collaboration from cross-system stakeholders, held the Summit on Improving the Court and Community Response to Those with Mental Illness in New Mexico in October 2022. Leaders from all three branches were enthusiastic about the opportunity to work together on familiar faces issues through this project.

There is hope, vision, and robust leadership in New Mexico. It is a region with immense demographic diversity and unique cultural practices shaped by large Latino, Chicano, Hispanic, and Tribal communities and 23 sovereign Tribal Nations. State and local policymakers and community members are united in seeking better, trauma-informed, human-centered, evidence-based approaches to treating individuals with behavioral health needs.

Familiar Faces in New Mexico

Counties across New Mexico have been at the forefront of building services and supports for familiar faces. In Bernalillo County, the population center of New Mexico, leaders have developed practices to identify and track familiar faces who have had a high number of jail bookings and emergency department visits. In rural counties, such as Otero and Grant Counties, leaders have created formal and informal partnerships among local stakeholders to facilitate information sharing about people who are familiar faces and to coordinate appropriate wraparound services for these individuals.

State leaders saw an opportunity to partner with county leaders to collaborate and strengthen efforts to improve outcomes for people who are familiar faces. With support from the state legislature and judicial branch, the executive branch requested training and technical assistance from the CSG Justice Center to advance the state’s familiar faces work. In spring 2022, New Mexico joined the SSFF Project, committing to an 18-month effort to create state and local policy strategies to address the needs of familiar faces.

The newly established New Mexico Supreme Court Commission on Mental Health and Competency created the States Supporting Familiar Faces Ad Hoc Subcommittee under the Commission as a home for the project. The subcommittee’s three co-chairs represented the three branches of state government. The co-chairs recruited an array of state and local stakeholders to join the subcommittee, including members from multiple state agencies, behavioral health service providers, community-based organizations and advocacy groups, and county leaders. The New Mexico Office of Peer Recovery and Engagement helped identify leaders in the peer support community who could inform the project’s policy strategies with their lived experience.

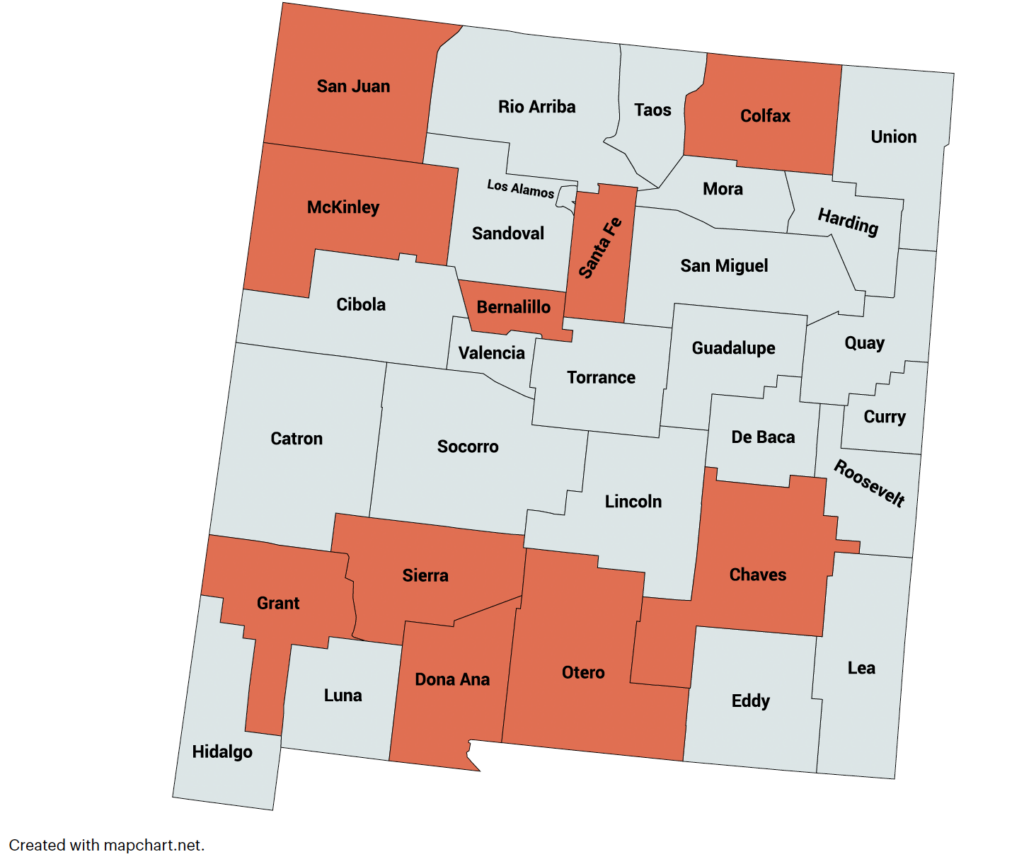

Coalition of Counties

Ten counties in New Mexico volunteered to work with their state counterparts on the SSFF Project. The cohort of SSFF counties included rural, suburban, and urban, as well as well-resourced and under-resourced communities. County representatives attended subcommittee meetings to share information between local teams and the subcommittee. The CSG Justice Center hosted virtual convenings over a 12-month period, from August 2022 to August 2023, with the county teams and facilitated numerous meetings with individual county teams and a broad range of subject matter experts from around the state to build the project’s state and local communication, planning, and collaboration infrastructure.

New Mexico States Supporting Familiar Faces Counties

Promising Practices that Came from Local Communities

The SSFF counties came to the project with a wealth of local lessons and promising practices that the state was keen to support, replicate, and expand across New Mexico.

• In Otero County, stakeholders from the hospital, jail, police department, and treatment centers met monthly to identify and discuss local people who are familiar faces. This informal but impactful meeting allowed cross-system entities to track and develop care plans for individuals.

• Leaders in Grant County have used state funding to provide planning support to individuals as they exit jail and connect them to medication-assisted treatment (MAT) in the community.

• Santa Fe County implemented a referral management technology platform that allows cross-system stakeholders to view, track, and follow up on an individual’s different referrals.

• Doña Ana County built a “no wrong door” crisis triage center where individuals in crisis could receive immediate support and connections to behavioral health services rather than go to jail.

• Chaves County formed a behavioral health leadership council to convene cross-system behavioral health stakeholders. One of the council’s objectives is to remove the silos among service providers so that individuals receive a coordinated response for their needs.

Seeking Out Advisement from People with Lived Experience

The project drew on the robust expertise of New Mexico’s community of certified peer support workers (CPSWs), practitioners, and people with direct experience in justice and behavioral health systems. The CSG Justice Center team hosted five community dialogue sessions that invited people with lived experience to share their expertise, insights, and recommendations for how to improve local systems. Some of the findings from the community dialogues were as follows:

• There are major barriers to accessing housing and transportation for people navigating treatment for SUD and reentry from incarceration, especially in rural areas of the state.

• There are immense gaps in resources, including SUD treatment access, workforce shortage, mental health resources, social support, and culturally affirming and culturally informed services.

• CPSWs provide a crucial connection between individuals in recovery and services and supports.

• Coordinating care, services, and supports among state and local governments and Tribal Nations, Tribal communities, and Pueblos can be complex, and there is openness to strengthening collaboration.

• Peers function as system-level leaders in their communities who are working to improve outcomes. The CPSWs that CSG Justice Center staff spoke with have important knowledge they want to share with policymakers and program decision-makers about people in recovery, people who use drugs, and people with serious mental illness.

Identifying Policy and Funding Strategies to Improve Responses to Familiar Faces

Priorities Articulated by the Familiar Faces Subcommittee

During the county convenings, local leaders shared the challenges, gaps, and opportunities that each county is experiencing. Leaders also articulated what would make the SSFF project a win in their communities. The subcommittee prioritized the following challenges for policy action, including legislative, budgetary, or administrative action:

• Lack of capacity across local systems and stakeholders to collect, use, and share data to identify and coordinate care for familiar faces

• Severe behavioral health workforce shortages

• Lack of access to MAT, specifically in rural areas and in jails

• The need for coordinated local systems of care that include cross-system collaboration, telehealth, mobile crisis response, diversion options, and community-based services

• The backlog of competency to stand trial cases

• Lack of availability and access to different types of housing for people who are familiar faces

• The need to expand availability of broadband internet to support access to telehealth care

This list of challenges and opportunities informed the policy recommendations that the subcommittee developed. The subcommittee met bimonthly through the fall of 2022 to discuss recommendation ideas and unanimously approved 8 recommendations (see the table below) that were submitted to the New Mexico Supreme Court Commission on Mental Health and Competency in December 2022.

Supporting Implementation of Reforms and Scaling Successful Approaches

The subcommittee began working on implementation of policy recommendations in 2023. The recommendations were advanced and implemented through a variety of mechanisms, including legislation passed in the 2023 legislative session, administrative collaboration among several state agencies, and policy and practice changes at the local level.

Some of the policy recommendations with a longer timeframe will be implemented through a Competency Diversion Pilot project established by the New Mexico Supreme Court Commission on Mental Health and Competency. The project will be launched in four judicial districts where state and local cross-system stakeholders will collaborate on building local coordinated systems of care, which will accomplish several of the subcommittee’s recommendations.

The remaining long-term recommendations will move forward through the New Mexico Supreme Court Commission on Mental Health and Competency’s Teams, which are focused on building a forensic community behavioral health system in New Mexico.

The table below shows each policy recommendation and its implementation status as of the publication of this case study.

|

Policy Recommendation |

Implementation Status |

|

Strengthen data collection, use, and sharing. |

The CSG Justice Center provided suggestions for how the state could use data in the New Mexico dataXchange, a data sharing platform maintained by the AOC that houses criminal justice data from state and local agencies, to identify people who are familiar faces and track their outcomes across different systems. These have been provided to the Behavioral Health Services Division (BHSD) and the governor’s office to identify state agencies and departments to lead the analysis and plan its uses. This planning is expected to be complete by early 2024. |

|

Expand access to MAT, specifically in rural areas, and provide training to judges and court staff on the science and efficacy of MAT. |

Implementation of some of the SSFF MAT policy recommendations is taking place through the state supreme court’s Competency Diversion Pilot project to build a local forensic community behavioral health system in four judicial districts. When individuals served by the pilots require MAT services, the pilots will address access and linkage to care. The pilot project planning started in July 2023; local pilots are expected to begin going live in early 2024. The Court Education Institute within the AOC is developing training on MAT for judges and court personnel that is planned to be offered in summer 2024. |

|

Leverage state funding to build local capacity to support people who are familiar faces. |

The New Mexico BHSD has hosted feedback sessions with state and local stakeholders to identify burdensome application and reporting requirements in state grant programs that may prevent local agencies and under-resourced communities from applying for or securing grant funding. These stakeholders offered impactful suggestions for simplifying state grant processes, which would alleviate some challenges that applicants, especially smaller rural counties with few grant-writing resources, face when seeking state grants. The BHSD is working with the state procurement office to implement stakeholder recommendations for the next grant cycle in 2024. |

|

Revise state statutes to replace outdated language related to intellectual and developmental disabilities. |

Subcommittee members led the process of identifying relevant statutes, developing a multiyear plan to revise those statutes, drafting legislation, and winning passage of the legislation. Governor Lujan Grisham signed the bill on April 4, 2023. |

|

Expand housing options for people who are familiar faces. |

Housing-related policy recommendations are incorporated within the state supreme court’s Competency Diversion Pilot project. State agency staff are working collaboratively with local teams in the four pilot judicial districts to identify local housing organizations, leaders, and stakeholders and to develop and implement the housing support components of the project. The pilot project’s co-chairs hold monthly meetings with state-level housing leaders to coordinate on focusing state housing resources within pilot judicial districts. The pilot project launched in July 2023. Pilots will be going live in early 2024. |

|

Adopt statewide definitions of serious mental illness, recidivism, and homelessness. |

The New Mexico Human Services Department (HSD) has published a standardized definition of serious mental illness in its Behavioral Health and Billing Policy Manual, which is used by state agencies that bill the Human Services Division for behavioral health services. The BHSD and the Behavioral Health Collaborative are collaborating with other state agencies, including the Corrections Department, the AOC, the governor’s office, the Department of Health, and the Law Office of the Public Defender, to implement the HSD definition of serious mental illness in 2024. |

|

Reform the competency to stand trial process to improve outcomes for people who are familiar faces. |

The CSG Justice Center provided information and support to a team of cross-system stakeholders with representation from all three branches of state government as they drafted legislation to overhaul the competency to stand trial process. The legislation includes diversion prebooking and pretrial options; off-ramps for misdemeanor cases; options for community-based outpatient evaluation and restoration; warm handoffs to community-based services; options for civil commitment and assisted outpatient treatment; and a system navigator position to assist individuals in moving through the process. The timeline for introducing the legislation was being finalized as this case study went to press. |

|

Develop standardized metrics to measure the impact of policy changes. |

Lead staff within the BHSD, Department of Health, and the AOC are finalizing four metrics related to familiar faces who have been identified as having serious mental illness and the disposition of competency cases to measure the impact of policy and practice changes. Under the leadership of the BHSD, the governor’s office and data and research staff in the division are planning to begin implementation in early 2024. |

Endnotes

1. E. F. Torrey et al., The Treatment of Persons with Mental Illness in Prisons and Jails: A State Survey (Arlington, VA: Treatment Advocacy Center, 2014); “Mental Health Facts in America,” National Alliance on Mental Illness, accessed March 8, 2022, https://www.nami.org/nami/media/nami-media/infographics/generalmhfacts.pdf.

2. Email correspondence between CSG Justice Center staff and Bernalillo County staff, September 2021.

3. New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee, Progress Report: Addressing Substance Use Disorders (Santa Fe, NM: New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee, 2023), 6, https://www.nmlegis.gov/Entity/LFC/Documents/Program_ Evaluation_Reports/Progress%20Report%20Addressing%20Substance%20Use%20Disorders,%20August%202023.pdf.

4. “Drug Overdose Mortality by State,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/drug_poisoning_mortality/drug_poisoning.htm; “Total Alcohol-Induced Death Rate,” KFF, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/alcohol-induced-death-rate-per-100000-population/?curren tTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Alcohol-Induced%20Deaths%22,%22sort%22:%22desc%22%7D.

5. New Mexico Legislative Finance Committee, Progress Report, 6.

6. “Quick Facts: Sierra County, New Mexico,” U.S. Census Bureau, accessed September 8, 2023, https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/sierracountynewmexico,NM/PST045222.

Project Credits

Writing: Amy Button, Ryan Carlino, CSG Justice Center

Research: Ryan Carlino, Mari Roberts, CSG Justice Center

Advising: Hallie Fader-Towe, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Leslie Griffin, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Web Development: Yewande Ojo, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Kevin Dugan, CSG Justice Center

About the Authors

New Mexico launched a pilot program in 2024 to divert people with mental health needs and misdemeanor charges…

Read More From Courtroom to Care: 5 Key Strategies Behind New Mexico’s Competency Diversion Pilot

From Courtroom to Care: 5 Key Strategies Behind New Mexico’s Competency Diversion Pilot

New Mexico launched a pilot program in 2024 to divert people with…

Read More