Stepping Up Monterey County System Mapping Project

As part of their Stepping Up initiative, leaders in Monterey County, California, engaged the CSG Justice Center to work with county stakeholders to map current policies, processes, and resources for people with behavioral health needs who enter the criminal justice system. This report presents recommendations for system improvements, including feedback from community members who have had firsthand experience with behavioral health services and the criminal justice system in Monterey County. Photo credit: McGhiever via Wikimedia Commons under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Introduction

The Monterey County, California, Board of Supervisors passed a Stepping Up resolution in April 2019, joining a national movement to reduce the number of people in their local jail who have mental illnesses and co-occurring substance use disorders.

In keeping with the mission of the Stepping Up initiative, Monterey County Behavioral Health asked The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center to work

with stakeholders in the county to map current policies, processes, and resources for people with behavioral health needs who enter the criminal justice system. Co-led by Monterey County Behavioral Health, Monterey County Sheriff’s Office, and Monterey County Probation Department, the Stepping Up Monterey System Mapping project kicked off in February 2020.

COVID-19 Context

Due to the pandemic and associated challenges facing the county’s criminal justice and health systems, the mapping project was temporarily put on hold. Like other communities across the country, Monterey County has worked to provide continued services throughout the pandemic, including by redeploying its Mobile Crisis Team to support other essential services and expanding the use of telehealth. Between January and June 2020, the jail’s average daily population (ADP) dropped approximately 20 percent from 821 to 655. This occurred as a result of the zero bail order put in place throughout the state, which reduced pretrial detention, and efforts to foster early release where it could be accomplished safely. However, as other jurisdictions have experienced, the jail population on psychotropic medications did not see a similar drop: it went from 312 people in January to 302 in June, a reduction of only 3 percent. The second half of 2020 saw ADP climb back to 836 people by year-end, while the population on psychotropic medications also climbed, hitting a high of 376 people in October and November before dropping to 352 at year-end. Starting in April 2020, the number of people on psychotropic medications was consistently above 40 percent of the ADP.

Methodology

The project was re-launched in January 2021, when enough processes had stabilized for a fruitful system mapping discussion. Over the course of four virtual focus groups, CSG Justice Center staff and consultants heard from government stakeholders, behavioral health providers, and people with firsthand experience in the criminal justice and behavioral health systems. These groups spoke about their priorities for the project, their understanding of how the system currently works, and recommendations for improvement. Follow-up interviews filled in details and reconciled inconsistencies, and then a draft map with emergent recommendations was presented to the project’s leadership group, including leadership from the chief administrative office, jail command, probation, behavioral health, prosecution, defense, the courts, and the police departments of Monterey, Greenfield, and Salinas.

Over 30 people participated in mapping focus groups and interviews. The CSG Justice Center team also reviewed available aggregate data from the Jail Profile Survey administered by the Board of State and Community Corrections, the 2019 Monterey County Homeless Census and Survey produced by Applied Survey Research, and special reports. These reports enabled a broad understanding of dispatch calls coded for involuntary holds and mobile crisis, the number of people on psychotropic medications in jail, the incidence of behavioral health needs and justice system involvement among people experiencing homelessness, the number of applications for mental health diversion, and the number of people engaged in various treatment modalities. Analysis and matching of individual-level data were beyond the scope of this project. However, that analysis would be helpful for the county’s future efforts to more precisely understand how people are moving through the criminal justice system and the unmet needs for community-based treatment and supports, such as housing.

Stepping Up Framework

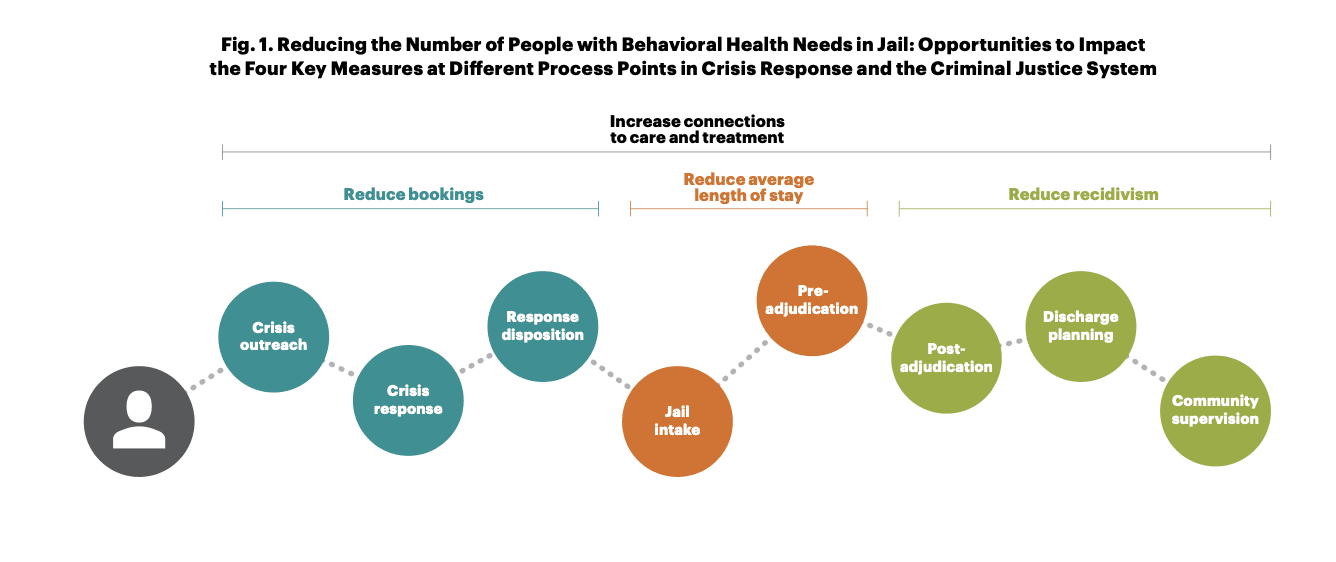

The Stepping Up initiative encourages local stakeholders to reduce the prevalence of behavioral health needs in jail by impacting four key outcome measures:

- Reduce bookings;

- Reduce average length of stay;

- Increase connections to care and treatment; and

- Reduce recidivism.

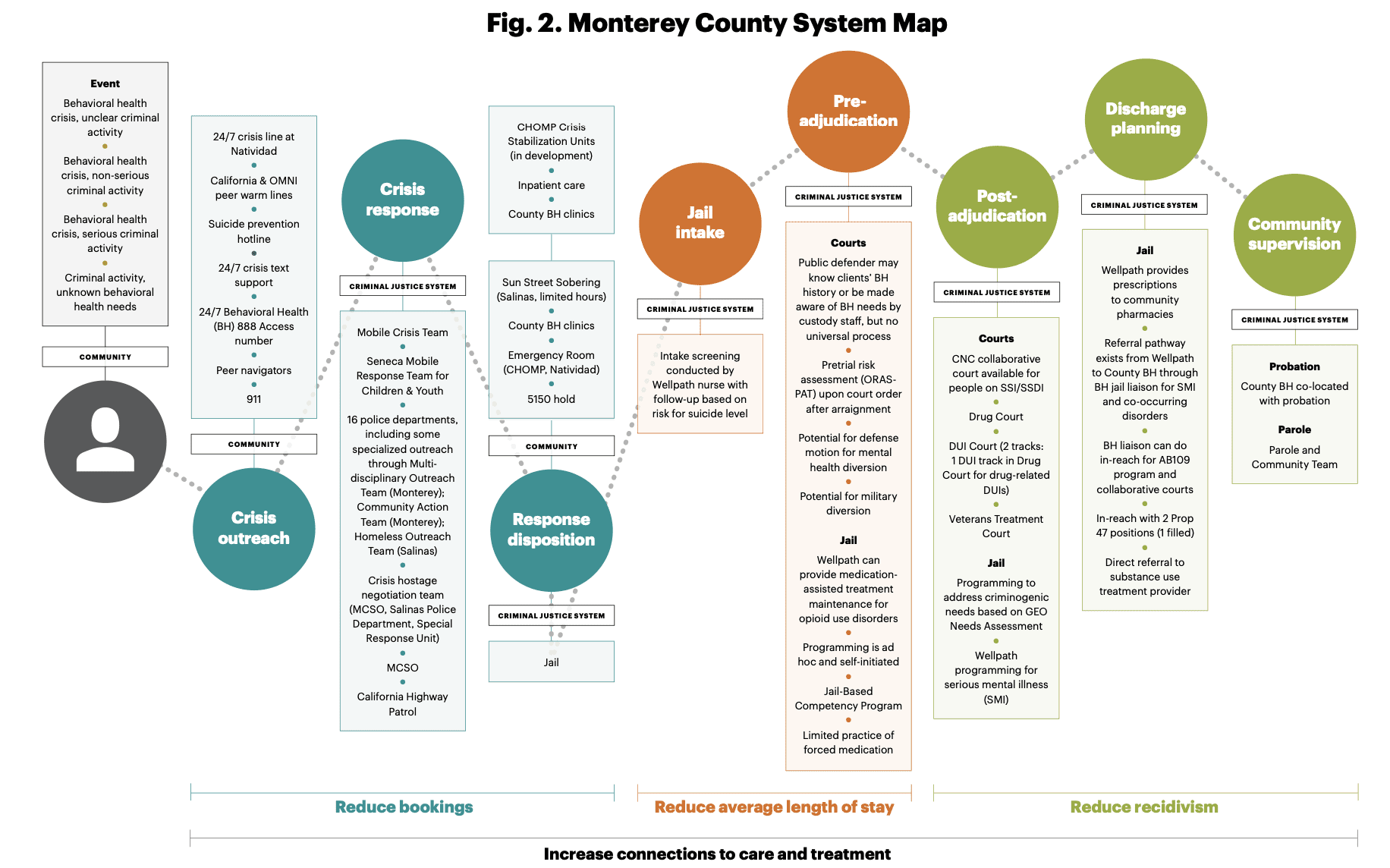

The CSG Justice Center team developed Monterey County’s system map and recommendations to highlight opportunities to impact these key outcomes (see Fig. 1 and 2).

Findings

1.

Cross-system coordination occurs in a variety of ways throughout the county. However, it generally happens within specific programs, such as specialized response teams, the collaboration between probation and behavioral health for people supervised under AB 109, and the collaborative courts. Otherwise, coordination often occurs on a case-by-case basis, such as when Monterey County Sheriff’s Office (MCSO) brought a person leaving the jail who needed transportation to a County Behavioral Health clinic.

2.

Given the ad hoc nature of these coordination efforts, individuals often “fall through the cracks” during transitions, such as following emergency room discharge and release from jail.

3.

People with firsthand experience of the criminal justice and behavioral health systems and their families often find current policies, processes, and eligibility criteria difficult to understand and navigate.

4.

Some focus group members expressed concern about whether community-based treatment and supports are available on an equitable basis—in particular, whether people of color are more likely to be taken to secure settings such as the jail than White people.

Recommendations

The following recommendations draw from conversations with focus group members, as well as the CSG Justice Center’s experience with similarly situated jurisdictions across the country. The recommendations were previewed with the Monterey County leadership group and refined based on their input.

1. Improve cross-system collaboration

A. Establish a regular forum for interagency information sharing and development of new initiatives across justice, health, and housing/homelessness services. Both leadership and line staff would benefit from opportunities to regularly review data and jointly develop new policies and processes. This forum may take place in quarterly meetings with this project’s leadership group or as a standing set of agenda items for a pre-existing countywide entity, such as the Community Corrections Partnership. Leadership should also help establish a regular forum for a cross-system group of line staff to meet to review data, collaboratively address emergent challenges, and identify issues for elevation to leadership.

B. Reinstitute a forum for contracted providers to meet regularly to share information. Navigator U was suspended due to COVID-19, and providers reported missing the opportunity to understand available resources and potential partners. Since this recommendation was initially raised during focus group meetings, Navigator U has been reinstated as a virtual meeting. The Housing Assistance Team and Support is another venue for sharing information about available services among providers.

C. Develop and provide training on mental illness, substance use disorders, and co-occurring disorders for various justice partners. For example, the county could provide training on mental illness for dispatch personnel, build on existing Crisis Intervention Team training for law enforcement, and train attorneys, judges, and jail staff on behavioral health needs.

D. Analyze data to inform cross-system decision-making. Conduct initial analyses to develop a shared picture of who is booked into jail, how long they stay, and jail disposition. Jail leadership indicated that if a list of medications prescribed to treat serious mental illness (SMI) is developed, a manual review process could identify people with SMI, leading to an analysis of their charges, average length of stay, and jail disposition. This analysis would help all stakeholders better understand the jail’s SMI population and whether they might be eligible for pretrial release, mental health diversion, or disposition through a collaborative court. The second phase of analysis should bring together data on recidivism and connections to community-based treatment and housing. This phase should include analyses to identify any inequities in how various racial, ethnic, linguistic, or socioeconomic groups are accessing treatment and housing before or after jail or emergency room visits. A third phase should review current expenditures relevant to this population across different agencies to determine potential ways to spend money more effectively. This sort of analysis in other California counties has led to identifying opportunities for better system spending.1

2. Reduce jail bookings for people with behavioral health needs

A. Restore the Mobile Crisis Team. All of the focus groups raised the loss of this team as an important cause for concern. Following this, the team was reactivated as of May 10, 2021. Additional interviews led to training Mobile Crisis staff on accessing the Coordinated Entry System for housing, an important part of giving people needed supports in the community. (See recommendation 4d for more on Coordinated Entry.)

B. Provide additional training to law enforcement on interacting with people who have behavioral health needs. Focus group participants who had firsthand contact with the criminal justice system made a number of suggestions in this regard. For example, they raised strategies, including specific questions, for law enforcement to use when they come in contact with a community member who seems to be exhibiting symptoms of mental illness or addiction.2 Additional coordination with the Coalition of Homeless Service Providers, the U.S Department of Housing and Urban Development Continuum of Care for Monterey and San Benito Counties, will allow law enforcement to make connections to housing for people who need it.

C. Develop recommended pathways that make it easier to get people into treatment instead of jail. Referrals are currently dependent on the responder knowing about alternatives to jail and the hospital. As such, there is a need to develop written referral pathways with decision trees that can help crisis responders understand the full range of options for resolution. This will ensure appropriate usage of expensive locations such as emergency rooms and jail and improve the current underutilization of alternatives, such as the Sun Street Sobering Center. Interagency and community groups can develop these decision trees, with participation from key law enforcement agencies, hospitals, contracted behavioral health care providers, peer support specialists, and community members.

D. Increase capacity of social workers and peer specialists. Peers and social workers reported that they are unable to respond to all of the requests for their time and assistance—in responding to crises, stabilizing crises, and supporting reentry. The 2020 passage of SB 803 provides additional structure and potential Medi-Cal funding for certified peer specialists.

E. Expand non-emergency room options for crisis response and stabilization. Stakeholders reported that there is sufficient demand for expanding the hours at the Sun Street Sobering Center in Salinas, completing the establishment of crisis receiving services at Community Hospital of Monterey Peninsula (CHOMP), and, ideally, establishing additional capacity elsewhere in the county. The county should consider conducting a time-limited study of 911 calls with additional coding to help identify calls for service that could be resolved through drop-off at a crisis receiving center or non-emergency crisis stabilization. This could help document the need for such a facility and identify an appropriate location for it, potentially further south than existing options.

“The most important part is getting police officers informed. They have to know resources. They have to know where to take people.”*

3. Reduce jail bookings for people with behavioral health needs

A. Develop strategies to share mental health information with defense counsel to facilitate earlier identification for potential diversion or other programming. Defense counsel reported that they are only likely to become aware of a client’s behavioral health needs if a custody officer mentions it to them or if they have represented the client before. Jail, Wellpath, and defense counsel can work together to develop a process for uniformly informing counsel if their client screens positive for a mental illness or substance use disorder.

B. Consolidate behavioral health matters in court calendars. The current system for calendaring criminal court cases can require attorneys, as well as County Behavioral Health, to cover multiple courtrooms and times to be present for cases involving people with behavioral health needs. Bringing cases together when behavioral health diversion is being considered or when a defendant has an identified behavioral health need can allow a smaller group of judges, court administrators, and attorneys to develop more expertise in handling these matters while streamlining court appearances for County Behavioral Health. This may allow the courts to reduce continuances on these cases and thereby reduce time to disposition and time in jail.

“If you know where to go, it’s there. But it depends where your mind state is whether you can access those resources.”

C. Analyze the current medications and charges for people in custody. Conducting this analysis over a limited time period, such as one month, would help stakeholders estimate appropriate numbers for mental health diversion and other alternatives to incarceration, such as pretrial release and post-disposition collaborative courts.

i. With the California Supreme Court ruling that people may no longer be detained solely because they are unable to meet financial conditions of release,3 communities around the state will be rethinking pretrial release processes. An opportunity exists for early identification of behavioral health needs and connections to care in the community for people who would otherwise have been detained before trial.

ii. This analysis could also inform decision-making about target populations for collaborative courts to ensure that these programs are being used to their full potential. For example, focus group members reported particular interest in whether a collaborative court could be developed for people with co-occurring mental illnesses and substance use disorders who currently are not eligible for existing programs. Participants also expressed interest in expanding the eligibility of the Creating New Choices (CNC) program beyond individuals on Supplemental Security Income and the Social Security Disability Insurance Program (SSI/SSDI).

4. Increase connections to treatment and reduce recidivism

A. Establish a strategy for proactive community outreach to raise the visibility of and improve access to existing services. People with firsthand experience of these services reported that it is difficult to access treatment and housing “unless you enter through the right silo.” They offered a number of ideas for public information campaigns to increase understanding of existing community-based treatment and housing options, including signs at bus stops, social media, and information supplied by primary care physicians. Continued work with similar focus groups and the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) could help direct these efforts.

B. Increase available treatment and programming for people with behavioral health needs in custody. Existing screening by Wellpath, Monterey County Jail’s contracted mental health provider, should be given to all individuals entering the facility to identify mental health and substance use treatment needs. Efforts should be made to increase the availability of treatment and programming for people who are detained before trial or held in administrative segregation, as both of these groups

“Lots of folks don’t have phones; giving them a number or an appointment down the line isn’t practical.”

C. Develop or formalize a transition planning process that includes Medi-Cal reactivation and warm hand-offs to treatment and services, potentially with peer navigators. While specific protocols exist for discharging some individuals held in Monterey County Jail, a more comprehensive approach to discharge planning would increase the county’s ability to leverage Medi-Cal to pay for community-based care and increase the likelihood that referrals to service become true connections to care. Discussions underway through the California Advancing Innovations in Medi-Cal (Cal AIM) process will create new opportunities for ensuring that people coming into jail on short stays do not lose coverage and that reentry planning is covered for people staying longer than 30 days. A separate strategy should be developed for “unplanned” discharges, which requires coordination with the courts. In addition, focus group members noted that people discharged on the weekend or at night would be more likely to “fall through the cracks” because community-based providers were not open at those times. A formalized transition process could help prevent these gaps. All discharge planning should include assessment for housing needs and connection to the Coalition of Homeless Services Providers.

Another strategy that many counties use is a single coordinated community center or reentry office that serves everyone returning from jail and prison and combines community corrections, treatment, and services organizations, and community groups under one roof.

D. Expand the use of Coordinated Entry by justice partners and local hospitals. Coordinated Entry is the system for matching individuals with housing resources based on the acuity of need. If jail, probation, and parole staff, as well as the local hospitals, are familiar with Coordinated Entry and able to place people on the referral list, Monterey County can ensure that people in contact with these agencies are connected to the housing system.4 This will also allow Monterey County to keep a more accurate record of housing needs.

E. Expand the use of peer navigators for care coordination in the community. As discussed above, peer specialists and social workers can play an important role in ensuring that people are connected with appropriate treatment and supports. Unwillingness to engage in treatment came up in focus groups of people with firsthand experiences and justice system partners. Certified peer specialists, particularly those who have experience with the criminal justice system, can play an important role in promoting treatment, overcoming obstacles to accessing care, and navigating setbacks.

“Now I have a good support system, and it’s not just my family. It includes my probation officer, my sponsor, the staff at my provider.”

Monterey County has successfully developed an impressive range of strategies for connecting people with behavioral health needs to community-based care, including several specialized response teams within a number of police departments, a Mobile Crisis Team, mental health diversion, medication-assisted treatment in the jail, a range of collaborative courts, and a collaboration among probation, parole, and County Behavioral Health. It is clear that the individuals tasked with tackling this challenging issue in Monterey County genuinely care about improving the lives of people with behavioral health needs and are committed to reducing the use of jails whenever possible. The recommendations in this report aim to help local stakeholders scale up their efforts so that more people can access needed care and housing, rather than cycling through the criminal justice system.

Footnotes

1 For examples of this approach, see CSG Justice Center, Integrated Funding to Reduce the Number of People with Mental Illnesses in Jails:

Key Considerations for California County Executives (New York: CSG Justice Center, 2018), https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/integrated-fund-ing-to-reduce-the-number-of-people-with-mental-illnesses-in-jails-key-considerations-for-california-county-executives/.

2This detailed list will be provided in writing to members of the leadership group for their reference.

*Quotes in this report are all from anonymous focus group members who have firsthand experience with the criminal justice and behavioral health systems in Monterey County.

3In re Kenneth Humphrey, Supreme Court of California, March 25, 2021, https://www.courts.ca.gov/opinions/documents/S247278.PDF.

4For further discussion, see CSG Justice Center, Reducing Homeless for People with Behavioral Health Needs Leaving Prisons and Jails: Recommendations to California’s Council on Criminal Justice and Behavioral Health (New York: CSG Justice Center, 2021), https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/reducing- homelessness-for-people-with-behavioral-health-needs-leaving-prisons-and-jails/.

Project Credits

Writing: Hallie Fader-Towe, CSG Justice Center; Elizabeth Siggins, Project Consultant

Research: Hallie Fader-Towe, CSG Justice Center; Elizabeth Siggins, Project Consultant

Advising: Joseph Hayashi, CSG Justice Center; Elizabeth Siggins, Project Consultant

Editing: Darby Baham, Emily Morgan, and Katy Albis, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Public Affairs: Ruvi Lopez, CSG Justice Center

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

As the Stepping Up initiative marks its 10th year, America’s justice and behavioral health systems are facing a…

Read More19 states were recently granted permission by CMS to reimburse critical reentry services with Medicaid funding for up…

Read More"It is the humane, person-centered approach that supports and stabilizes individuals, their families, and their communities."

Read More The 10-Year Impact—and Future—of Stepping Up: Facing the Behavioral Health Crisis in Jails and Communities with Real Solutions

The 10-Year Impact—and Future—of Stepping Up: Facing the Behavioral Health Crisis in Jails and Communities with Real Solutions

As the Stepping Up initiative marks its 10th year, America’s justice and…

Read More A “Once in a Generation Opportunity” to Improve Reentry for Nearly 2 Million People

A “Once in a Generation Opportunity” to Improve Reentry for Nearly 2 Million People

19 states were recently granted permission by CMS to reimburse critical reentry…

Read More Local Criminal Justice System Innovations in Mental Health Services: Q&A with CSG Justice Center Advisory Board Member Dr. Doreen Williams

Local Criminal Justice System Innovations in Mental Health Services: Q&A with CSG Justice Center Advisory Board Member Dr. Doreen Williams

"It is the humane, person-centered approach that supports and stabilizes individuals, their…

Read More