Each month, the Justice Center spotlights collaborative criminal justice/mental health initiatives that have received funding from the Bureau of Justice Assistance’s Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program (JMHCP). Justice Center staff members ask the practitioners in these programs to discuss some successes and challenges they have encountered in the planning and implementation process. This month’s profile is from the Los Angeles County, Calif., Sheriff’s Department, a 2009 expansion grantee.

Project Summary:

The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department (LASD), in collaboration with Special Service for Groups (SSG)—a community service provider, were awarded a 2009 JMHCP expansion grant to advance existing in-jail therapeutic services for people with mental illness and/or co-occurring substance use disorders. The LASD and SSG’s Project DIRECT (Direct Intervention for Re-entry through Employment, Counseling, and Treatment) already provides in-jail services that include education/GED preparation, peer-to-peer support groups, Moral Reconation Therapy treatment, and substance use disorder education. The expansion grant will facilitate an increase in treatment hours and add new services including trauma support groups, co-occurring support groups, housing education, and job skills/employment preparation and the development of comprehensive release plans for all clients.

How did your jurisdiction realize that there was a need to respond to the high prevalence of individuals with mental illnesses in the criminal justice system?

Due to the classification system in Los Angeles County jails, the prevalence of people with mental illnesses was self-evident. All prisoners with mental health concerns are housed in a special housing unit. At any one time, there are approximately 20,000 people in one of the eight Los Angeles County jail facilities. Of those, 2,000 people are housed in the designated mental health housing. There were certain statistics regarding those with mental illnesses that were particularly alarming; namely people with mental illnesses have an average length of stay of forty-six days, versus thirty-three days for people without mental illnesses. Second, recidivism for those with mental illnesses was high; 31–35 percent of those with mental illnesses have been incarcerated ten or more times.

Likewise, community providers were also keenly aware of their clients whose treatment was continuously disrupted by incarcerations. Providers working with the homeless population were especially concerned, as their clients, by virtue of being on the streets, were vulnerable to incarceration.

How did your initiative leverage pre-existing relationships?

In 2006, LA County was awarded a Mentally Ill Offender Crime Reduction grant from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Corrections Standards Authority, to help people in custody receive treatment and transition back into the community. With this award, all the partners, who were already directly working with this population, were motivated to create Project DIRECT. These partners include SSG, LASD, the LA Probation Department, LA County Public Defender’s Office, Hacienda La Puente Unified School District, Goodwill Southern California, and Recovery International. Whereas this collaboration is an impressive feat, it was an easy sell to the partners that saw positive results in a short time. For example, with the institution of Project DIRECT, there were no incidences of physical violence in the jail pod over an eighteen-month period, whereas typically there were three to four monthly incidences of violence.

What has been your greatest challenge?

Clients who are not facing a significant amount of prison time can be difficult to engage and may have low levels of motivation to create change in their lives. The collaboration with the court has been unparalleled in maintaining the success of clients, as the court can stipulate participation in Project DIRECT. When people are engaged in treatment, usually for about six months, they are able to see their own personal dreams and hope begins to resurface. However, fostering and strengthening a person’s motivation takes time, which is why the court’s participation is so important.

Provide an example of a particular success your program has had to date, either in moving from planning to implementation or in showing an impact on an individual, group, or community.

Through the alumni program, Project DIRECT keeps in touch with people who have graduated from the program. When clients are about to graduate, one of the program’s consumer employees meets with the person to discuss the alumni program, which includes monthly meetings and opportunities for graduates to contribute to community programs through offering services or being a mentor. Graduates are encouraged to contribute in ways that use their own strengths and interests. For example, one graduate began a creative writing group. Just last month, Project DIRECT received communication from a graduate who was placed on the dean’s honor list at Los Angeles City College. He has also been reunified with his children, and is working as an electrician while completing his college degree.

On March 9, 2024, President Joe Biden signed a $460 billion spending package for Fiscal Year 2024, allocating…

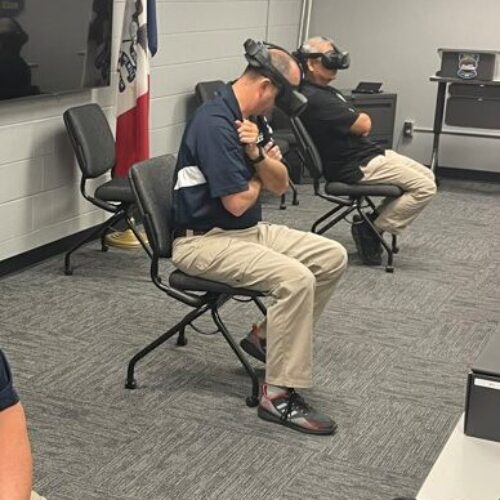

Read More Empathetic Policing: Mason City Police Department Launches Virtual Reality Training Program to Help Officers Better Understand Behavioral Health Crises

Read More

Empathetic Policing: Mason City Police Department Launches Virtual Reality Training Program to Help Officers Better Understand Behavioral Health Crises

Read More

Biden Signs Six-Bill Spending Package Funding Key Criminal Justice Programs

Biden Signs Six-Bill Spending Package Funding Key Criminal Justice Programs

On March 9, 2024, President Joe Biden signed a $460 billion spending…

Read More