As publicly-funded programs and services across the country are experiencing budgetary constraints, many are beginning to look to social impact bonds (SIBs), also known as pay-for-success bonds or social innovation financing, as a possible solution. Under the SIB model, public, private, and nonprofit sectors collaborate to achieve cost savings and improve social outcomes in areas such as criminal justice, juvenile justice, education, foster care, and homelessness.

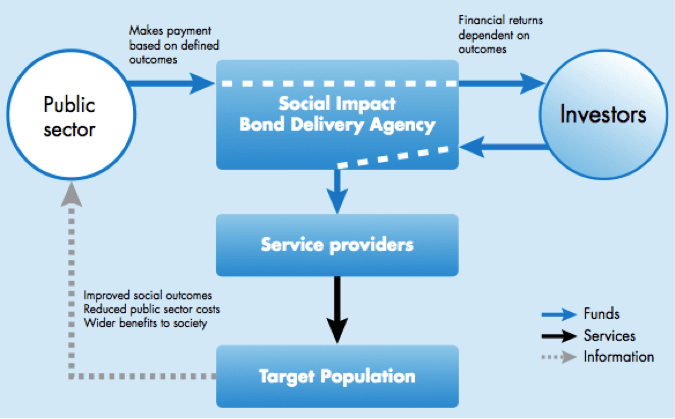

In this innovative model, four entities—a government agency, a private investor, a public or nonprofit service provider, and an intermediary organization—work closely together to implement an SIB bond project, and to support the development, implementation, or enhancement of a social program. Private investors provide funding in the form of a bond to a service provider that delivers social services to the targeted population. By providing the initial funding to the service provider, the private investor agrees to take on the financial risk that would traditionally be shouldered by the government. The intermediary organization—also known as the SIB delivery agency—oversees the project’s development, implementation, and assessment. The government agency—local, state, or federal—reimburses the investor if the program is successful, according to predetermined outcome goals and benchmarks of success. Examples of program outcome goals include reduced recidivism, increased employment, or reduced number of days incarcerated.

The benchmark of success is the point at which the government’s cost savings is equivalent to the dollar amount of the initial bond provided by the private investor. For example, a SIB criminal justice-related project with recidivism-reduction goals may determine that the benchmark is a 10-percent reduction in recidivism. In this scenario, at 10 percent, the government’s cost-savings related to recidivism reduction equals the initial SIB bond dollar amount. The project works under the assumption that lowering recidivism rates reduces the government’s spending related to crime and incarceration. If the project meets the benchmark of success, the government pays the investor the entire principal. If it exceeds the benchmark, the investor receives both the principal and a return on the investment in the form of an agreed upon percentage of the government’s cost savings. If the program does not meet the benchmark of success, the investor receives no payments in return. To determine whether these goals and benchmarks are met, the program’s performance is rigorously evaluated.

An illustration of the model is provided below.

Source: “Next Billion: Development through Enterprise,” available at http://www.nextbillion.net/blogpost.aspx?blogid=2179.

In August 2012, the first SIB project in the United States was launched in New York City, with the goal of reducing recidivism among youth ages 16 to 18 at Rikers Island, a jail complex located in New York City. The $9.6 million bond, funded by Goldman Sachs will be distributed in portions annually over four years to MDRC, the nonprofit organization overseeing the project. MDRC will transfer funding from the bond to the Osborne Association and Friends of Island Academy, two non-profit service providers that will provide therapeutic services to youth involved in the criminal justice system returning to their communities in New York City. If recidivism declines by at least 10 percent, Goldman Sachs will be reimbursed the full $9.6 million. If recidivism declines by 20 percent, it will make about $2.1 million in profit. This payment will be made five years after the project’s launch.[1]

Since the launch of the SIB project at Rikers Island, more criminal and juvenile justice systems in the U.S. have adopted pay-for-success programs. In September 2013, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) announced the investment of $24 million from its Workforce Innovation Fund to support SIB initiatives in New York State and Massachusetts. In New York State, the New York Department of Labor will partner with Bank of America Merrill Lynch and Social Finance to implement a $13.5 million, five-and-a-half-year pay-for-success project that will focus on reducing recidivism and increasing employment rates among individuals involved in the criminal justice system returning to their communities in New York City and Rochester. The Center for Employment Opportunities will provide life-skills training, transitional employment, and job placement and retention services to individuals returning home from incarceration. DOL will provide payments to investors during the first half of the project, while New York State will provide payments during the second half.[2]

“We are proud to be the first state in the nation to launch a pay-for-success, public-private partnership project to help put formerly incarcerated New Yorkers to work,” said Governor Andrew Cuomo in a public announcement. “This project is a win-win for our state.”

The second DOL-funded project is the Massachusetts Juvenile Justice Pay for Success Initiative, a $27 million, seven-year project, overseen by Third Sector Capital Partners. The initiative aims to reduce recidivism and increase employment rates among young men ages 17-24 who are at risk of reoffending, on probation, or leaving the juvenile justice system. Roca, Inc., the service provider, will provide outreach and life-skills and employment training to 929 young men returning to their communities.[3] “It is indeed possible to leverage the talent, resources, and expertise of partners with very different sets of expertise. We share the collective goal of helping high-risk young men stay out of prison and jail, get jobs, and create healthy lives for themselves,” said John Ward of Roca, Inc.

The state is also pursuing another pay-for-success project in partnership with the Massachusetts Housing and Shelter Alliance (MHSA) to reduce chronic homelessness in the state.[4] MHSA plans to build 380 more housing units for the chronically homeless through its Home and Healthy for Good program.[5]

At the federal level, the U.S. Department of Justice has also begun encouraging the use of social impact bonds. For some Second Chance Act grant tracks, priority consideration is given to applicants that incorporate SIBs in their work.

Additionally, in April 2013, Illinois Governor Pat Quinn announced an SIB project with the goals of decreasing recidivism, improving educational achievement, and increasing employment opportunities for youth involved in the juvenile justice system.[6] In September 2013, the Governor released a request for proposals, asking interested organizations to apply.[7] “The social innovation model is a unique way to invest in our community priorities without dipping into the pockets of Illinois residents,” said Governor Quinn in a public announcement.[8]

The United Kingdom was the first country to adopt SIBs, when in 2010 the Ministry of Justice and Social Finance, the third party intermediary, received £5 million from private charities and investors to provide services to individuals incarcerated at HMP Peterborough Prison, with the goal of reducing recidivism by at least 10 percent for each cohort or 7.5 percent overall.[9] The British Ministry of Justice recently reported that recidivism rates of individuals leaving Peterborough decreased by 12 percent, while recidivism rose 11 percent nationally.[10]

SIB advocates are optimistic that they will support promising but underfunded social programs. “One of benefits that come from the social impact bond model is that it forces the collaboration between the government, service providers, and private investors, aligning their efforts,” said Diane Lynch, the Chairman of the Board at Social Enterprise Greenhouse, an advocacy organization in Rhode Island that is currently researching the feasibility of SIBs in the state.

Some critics, however, have voiced concerns about SIBs. They worry that because of the high risk associated with these bonds, stakeholders and advocates may be tempted to distort evidence of their positive outcomes. “When you create a system that is founded on measuring certain results, it may lead to unintended consequences,” said Ms. Lynch. “For instance, in the educational sphere, two decades ago, under the federal government’s No Child Left Behind Initiative, many jurisdictions began creating their own curriculum in order to produce better testing outcomes among their students. This situation could occur with social impact bonds as well, and we should careful to make sure it does not.”

Additional Information about SIBs

- Nonprofit Finance Fund: Pay for Success Resources and Toolkit

- Prisoner Reentry Institute at John Jay College: Conference on Social Impact Bonds

- Urban Institute: Presentation at the 2011 American Society of Criminology Conference “Social Impact Bonds and Key Implementation Issues”

- Blue & Green Tomorrow: “Peterborough Social Impact Bond Showing Positive Results”

- Rand Corporation: Lessons learned from planning and early implementation of the Social Impact Bond at HMP Peterborough

[1] John Olson and Andrea Phillips, “Rikers Island: The First Social Impact Bond in the United States,” Community Development Investment Review , Federal Reserve Bank San Francisco, (2013): 9 (97- 101), available at http://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/rikers-island-first-social-impact-bond-united-states.pdf

[2] “Bank of America Merrill Lynch Introduces Innovative Pay-for-Success Program in Partnership with New York State and Social Finance Inc.,” Bank of America Newsroom, December 30, 2013, accessed February 5, 2014, available at http://newsroom.bankofamerica.com/press-releases/global-wealth-and-investment-management/bank-america-merrill-lynch-introduces-innovat.

[3] “Massachusetts Launches Landmark Initiative to Reduce Recidivism among High-Risk Young Men,” The Kresge Foundation, January 29, 2014, accessed February 5, 2014, http://kresge.org/news/massachusetts-launches-landmark-initiative-reduce-recidivism-among-high-risk-young-men.

[4] “Massachusetts First State in the Nation to Announce Initial Successful Bidders for ‘Pay for Success’” Mass.gov, August 1, 2012,available at http://www.mass.gov/anf/press-releases/fy2013/massachusetts-first-state-in-the-nation-to-announce-ini.html.

[5] “Social impact bonds hit Massachusetts,” Mission Investors Exchange, August 28, 2012, available at https://www.missioninvestors.org/news/social-impact-bonds-hit-massachusetts.

[6] “Governor Quinn Announces Illinois to Launch Social Impact Bond Program Grant from Dunham Fund to Strengthen State Social Innovation Efforts,” Illinois Government News Network, April 9, 2013, accessed February 4, 2014, available at http://www3.illinois.gov/PressReleases/ShowPressRelease.cfm?SubjectID=2&RecNum=11072http://www3.illinois.gov/PressReleases/ShowPressRelease.cfm?SubjectID=2&RecNum=11072http://www3.illinois.gov/PressReleases/ShowPressRelease.cfm?SubjectID=2&RecNum=11072.

[7] “Updated: Illinois Announces Pay for Success RFP for At-Risk Youth,” Nonprofit Finance Fund, accessed February 3, 2014, available at http://payforsuccess.org/resources/updated-illinois-announces-pay-success-rfp-risk-youth.

[8] “Governor Quinn Announces Illinois to Launch Social Impact Bond Program Grant from Dunham Fund to Strengthen State Social Innovation Efforts,” Illinois Government News Network.

[9] Emma Disley, Jennifer Rubin, Emily Scraggs, Nina Burrowes, Deidre Culley, “Lessons learned from planning and early implementation of the Social Impact Bond at HMP Peterborough,” May 2011, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/217375/social-impact-bond-hmp-peterborough.pdf.

[10] Isabelle De Grave, “Government Claims Success for Prison Social Impact Bond Pilots,” Pioneers Post, October 31, 2013, accessed February 4, 2014, available at http://www.pioneerspost.com/news/20131031/government-claims-success-prisons-social-impact-bonds-pilots.

In response to growing calls for police reform in New Jersey, particularly following the shootings of Najee Seabrooks…

Read More Three Things to Know About New Jersey’s Groundbreaking Community Response Legislation

Three Things to Know About New Jersey’s Groundbreaking Community Response Legislation

In response to growing calls for police reform in New Jersey, particularly…

Read More Apply Now: Join a Learning Community for Community and Crisis Response Teams to Improve Responses to Youth

Read More

Apply Now: Join a Learning Community for Community and Crisis Response Teams to Improve Responses to Youth

Read More

Apply Now: Join a Learning Community Focused on Substance Use and Overdose Community Response Programs

Read More

Apply Now: Join a Learning Community Focused on Substance Use and Overdose Community Response Programs

Read More