Planning, Implementing, and Assessing Law Enforcement Responses to Homelessness

Homelessness is a growing crisis in America, increasing by 12% between 2022 and 2023 alone. While there are a range of ideas about how to address this issue, in many places across the country, law enforcement officers are still typically the default first responders to these kinds of community concerns. This publication details how communities can strategically plan for and assess their law enforcement homelessness response efforts, using a shared vision, a logic model, and regular assessments to determine if the response is achieving its intended goals. It also discusses the importance of expanding the knowledge base of law enforcement practices and strategies to establish a set of national standards for effective and successful homelessness responses.

Planning, Implementing, and Assessing Law Enforcement Responses to Homelessness

Table of Contents

Click on a section to jump to it.

Introduction

Using a Logic Model for Strategic Planning

- Law Enforcement and Homelessness Service Systems Aligning and Sharing Goals

- 5 Steps for Building a Logic Model

- Questions to Consider While Building a Logic Model for Law Enforcement Homelessness Responses

Assessing the Law Enforcement Response to Homelessness

- 3 Steps to Prepare for Measuring Whether the Law Enforcement Response is Working

- Assessment Preparation Checklist

Appendix

- A. Sample Logic Model

- B. Sample Implementation and Outcome Measures

- C. Sample Data Collection Plan

- D. Sample Scope of Work

Endnotes

Introduction

Homelessness is a growing crisis in America, increasing by 12% between 2022 and 2023 alone.1 While there are a range of ideas about how to address this issue, in many places across the country, law enforcement officers are still typically the default first responders to these kinds of community concerns.

It’s easy to understand why.

People experiencing homelessness—whether in a rural, mid-sized, or large metropolitan area—often live near local businesses, homes, and schools where they and their behaviors are highly visible and attract a lot of attention. This can be especially true for people experiencing chronic homelessness2 who tend to cycle frequently between emergency services or have not engaged in treatment. Despite emerging initiatives such as community responder teams, mobile crisis units, and the national 988 lifeline, most Americans still call 911 and expect an officer to respond whenever they are experiencing an emergency or are concerned a person or situation is unsafe.

In 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned an appellate court decision finding a city’s anti-camping ordinance a violation of the Eighth Amendment. This decision reopened the door to camping bans,3 eliminating the perceived barrier to passing similar ordinances and enforcing them,4 and it has changed how many communities respond to homelessness. In some instances, law enforcement agencies—often in partnership with housing, medical, and social service providers—have created proactive outreach programs or approaches to address homelessness. In others, law enforcement’s role has been centered on encampment clearings and enforcement to keep people who are unhoused out of public view. Now leaders around the country have an opportunity to determine which responses are most effective in reducing homelessness and creating pathways for safer and thriving communities.

This publication details how communities can strategically plan for and assess their law enforcement homelessness response efforts, using a shared vision, a logic model, and regular assessments to determine if the response is achieving its intended goals. It also discusses the importance of expanding the knowledge base of law enforcement practices and strategies to establish a set of national standards for effective and successful homelessness responses.

Building a Knowledge Base of Law Enforcement Responses to Homelessness

Currently, there are no national, research-informed standards to guide law enforcement responses to homelessness. As a result, responses vary greatly across the country, often leaving individual officers or units with the burden of piecing together solutions to immediate concerns. This practice is not sustainable and will not lead to a widespread reduction in homelessness.

While there are differences in opinion on which responses are most effective, most reasonable people agree that it will take large-scale and systemic changes to truly address America’s homelessness crisis. An expanded knowledge base of law enforcement responses to homelessness is a critical step in making these changes and developing more effective, humane, and contextually appropriate strategies.

Law enforcement, with the help of researchers, can contribute to creating this knowledge base by engaging with their partners and setting shared goals for success and then reporting out what worked and what did not. This work will help to form a more comprehensive understanding of homelessness responses. And this understanding, in turn, can lead to national best practices that will inform the standards for all response models to reduce and end homelessness rather than exacerbate it.

Researchers at Indiana University and the University of Arkansas recently conducted a study to document and describe the diverse law enforcement responses to homelessness, both formal and informal.5 This research, including case studies and open source data collection, is a first step toward establishing a common language that law enforcement agencies and their cross-sector partners can use to facilitate communication and responses. It is also an important step to developing a framework that can guide strategy replication and evaluation. But more data are needed. Further research will also help improve transparency around what works and, ultimately, advance public safety.

Using a Logic Model for Strategic Planning

The components of any strategy for responding to homelessness, regardless of the lead agency, should begin with a clear vision and goals that are shared among partners. This level of cross-systems planning can help clarify the purpose of the response and uncover solutions previously not considered. The process of aligning goals also helps partners cultivate a better understanding of each other’s roles and responsibilities and identify where there may be gaps in services that need to be addressed. When planning a law enforcement response to homelessness, gaining the buy-in and visible leadership of police chiefs and sheriffs is also essential for positioning the response for success.

A logic model can be a very useful tool to support communication during this planning stage because it is a visual representation of a program or strategy that links activities to their purpose. For example, if local officials are planning to relocate people from an encampment, a logic model can demonstrate how coordinating with outreach workers can address needs that would likely result in people returning to the encampment a short time later if left unmet. Logic models also ultimately support assessments or evaluations of the implemented response because it is easy to visually see if the response met the intended purpose.

Because they are simple, concise visualizations that demonstrate a cause-and-effect relationship, logic models are also helpful for explaining new responses to people whose buy-in is needed for success, including potential funders. And they can aid in identifying metrics that are important to monitor and share with research partners and people invested in the sustainability of the initiative.

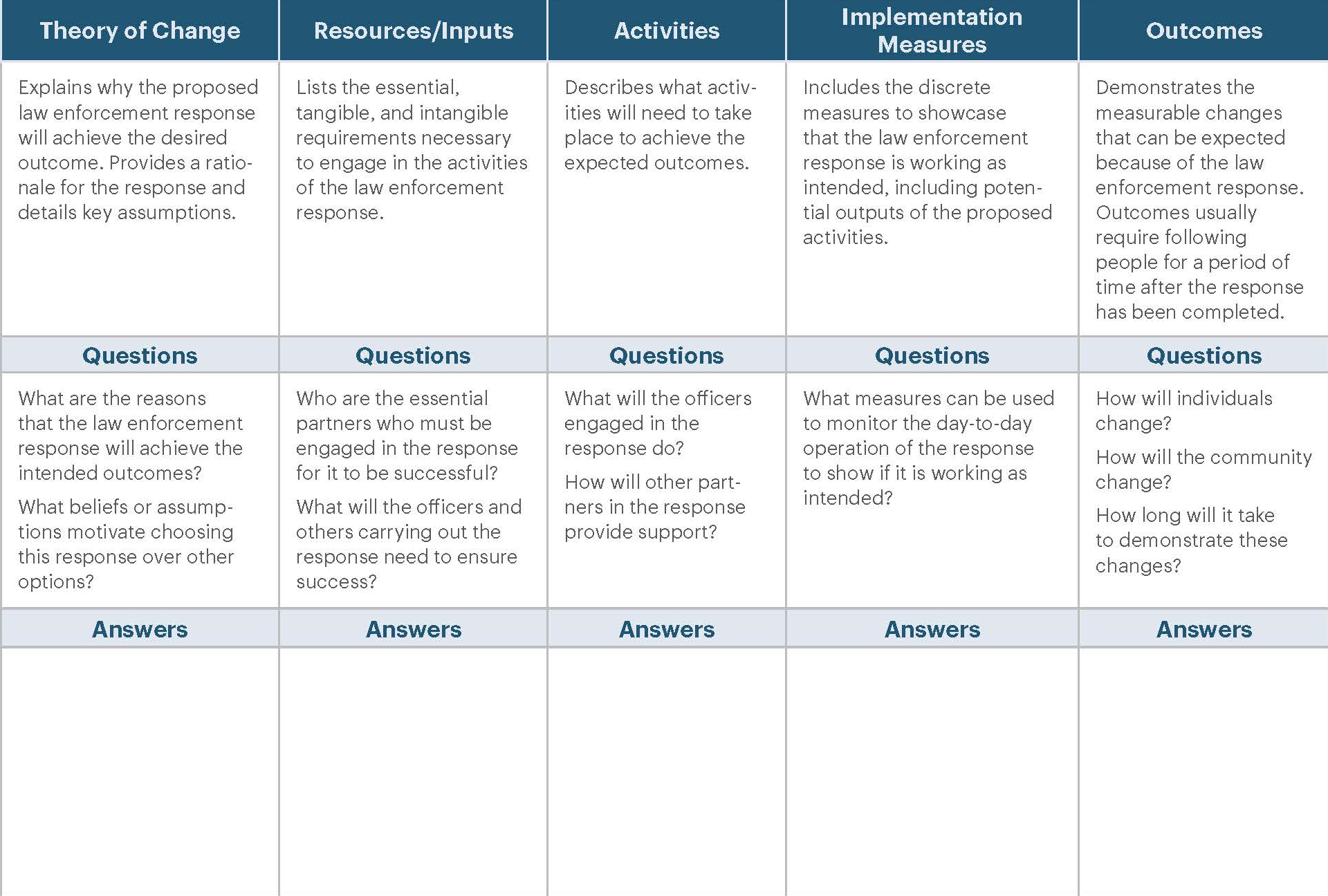

While there is no universal format or style, all logic models require agencies to answer a series of questions that will detail, at a high-level, how they can attain the desired outcomes. They are also best built in coordination with cross-systems partners from homeless services, public/behavioral health, and criminal justice, and in consultation with people who have lived experience. The following five steps, and complementary questions, will help law enforcement agencies and their partners plan out their homelessness response using a logic model for success.

Tip: Develop a sustainability plan that identifies stakeholders, partners, and funding sources, as well as the measures and messaging strategies needed to engage them. For more information about what sustainability can look like, see Sustainability in Action.

Law Enforcement and Homelessness Service Systems Aligning and Sharing Goals

While law enforcement responses to homelessness are frequently complaint-driven, officers in some jurisdictions have either purposefully or incidentally been performing outreach and connecting people to services that meet basic needs.6 Generally, the goal of street outreach is to connect people to a coordinated entry process that results in stable housing with supports in place to keep people housed long term and interrupt cycling among the homelessness, criminal justice, and behavioral health systems. Since stable housing has been shown to reduce arrests and time spent in jail7 and some routine activities are criminalized when people experiencing homelessness carry them out in public,8 communities may want to consider housing people as one of their long-term strategies to promote public safety. However, connecting people with complex needs (especially those who have lived unsheltered for a long period of time) to housing requires a broad base of support from the community rather than a single agency.9

5 Steps for Building a Logic Model

1. Articulate shared goals, assumptions, and a theory of change.10

It is important to understand and document any assumptions about how and why change is expected to occur. This process helps facilitate better communication among partners, implementation, and ultimately, assessment of how well the law enforcement response is working. Consider carving out a specific public safety goal that all partners can agree on and then use that goal to define law enforcement’s role in addressing homelessness.

2. Determine the resources needed to make the law enforcement response happen.

Consider what the response will need in terms of staffing and operations, direct service to individuals, and the connections and partnerships that must be in place to support it. These are the resources and inputs that make the work happen.

3. Specify what the law enforcement response will do.

Identify the activities that must take place to achieve the desired outcomes. This identification will help cross-systems partners determine what can be measured to show if the response is working as intended and effectively.

4. Develop implementation measures to track progress.

The work products, or outputs, of the activities performed can be translated into implementation measures that will be used to monitor the law enforcement response. Implementation measures help agencies determine if the planned activities are taking place as intended or if adjustments need to be made.

5. Identify the outcomes you want to see as a result of the work.

These outcomes should be realistic and in service of the identified public safety goal. Because success is judged by measuring whether outcomes are achieved, they must be both attainable and connected to a broadly supported purpose.

Use the guide below to create your own logic model with the information you have gathered, and share it with front-line staff, administrators, funders, community leaders, and people with lived experience to receive feedback on the law enforcement response’s design. Note: When planning a new response, it may help to identify the desired outcomes first, then determine what activities would result in those outcomes and what resources will be needed to fully implement the activities. Implementation measures should demonstrate that activities are being completed as designed.

Questions to Consider While Building a Logic Model for Law Enforcement Homelessness Responses

Download the Questions to Consider.

Assessing the Law Enforcement Response to Homelessness

As with any potential program or initiative, regular review of data can help law enforcement agencies better understand if their response is being implemented and working as intended or if adjustments are needed. Results from these assessments of data can also help officials communicate any accomplishments to the community or funders and, ultimately, improve fieldwide understanding of “what works.”

With careful coordination, the law enforcement response assessment should be a transparent, collaborative process that involves the people working directly on the response (that is, officers, dispatch call takers, homelessness service providers, administrators, research partners, and people with lived experience, etc.). If the partners completed the logic model during planning and reached agreement on implementation and outcome measures, assessing the law enforcement response will be the next step in using data to work toward the shared vision or goals. Preparing to assess the response can begin as soon as planning begins and may look different depending on the goals and what phase of development the response is in. Regardless of the desired outcomes, however, partners can measure whether any response is working by taking a few key steps.

3 Steps to Prepare for Measuring Whether the Law Enforcement Response is Working

1. Collect the right data.

Regular assessment begins with establishing a data collection plan first. Be sure to use your logic model to identify the data points that need to be collected to measure both implementation and outcomes. Each metric identified in the logic model should be included in the data collection plan. It’s also important to know where the data will come from and who can provide access. Make sure sufficient information is collected to identify participants in other systems if needed for outcome measures.

2. Report on implementation and outcome measures.

Creating a schedule identifying when implementation and outcome measures will be reviewed helps to develop a practice of regularly reviewing data. Some implementation measures, like call volume, may be reviewed daily or weekly, while other implementation measures, like use of diversion, can be reviewed monthly or quarterly. Typically, outcome measures are reviewed less often, such as annually, since they usually involve more time and may require collecting data from other sources. This type of routine reporting can also provide information needed to understand if there are issues with data quality. Note: Having quality assurance practices in place and automating analysis or producing detailed instructions for each measure ensures reporting is trustworthy and can build confidence in the assessment’s conclusions.

3. Engage a research partner—ideally at the outset.

In addition to providing expertise in research methods and statistics, research partners may be able to help with problem identification, strategic planning, providing information about evidence-based practices and recent research, and establishing better data collection practices. The role of the research partner is to provide a comprehensive and objective understanding of how well the law enforcement response works. For example, a research partner can identify sampling methods and ways to select participants for focus groups and surveys to ensure accurate representation of the community. A research partner can also help partners understand whether adjustments to the response should be made so that the identified goals can be achieved. A sample scope of work for engaging a research partner can be found in Appendix D.

Tip: Assessment encompasses a range of activities that serve different purposes depending on what information is needed. For a description of a variety of assessment strategies, see Choosing the Right Data Strategy for Behavioral Health and Criminal Justice Initiatives.

Download the Checklist.

Appendix

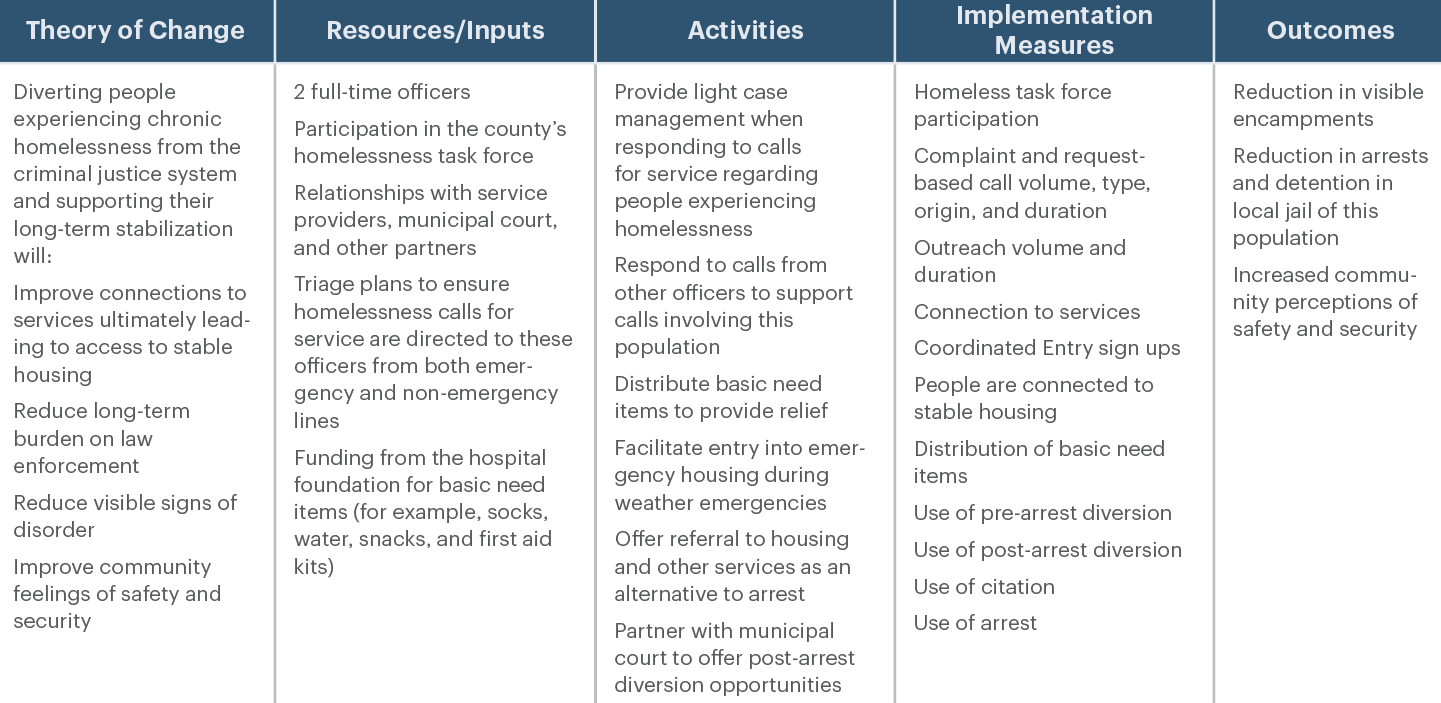

A. Sample Logic Model

This example of a logic model for a homeless outreach team, a team of law enforcement officers who engage in outreach and respond to calls related to homelessness, shows how a law enforcement response can be described to connect theory, operations, and outcomes, and develop associated metrics. It should be noted that other types of responses would be expected to lead to different outcomes, and the outcomes chosen should have a plausible connection to the activities performed.

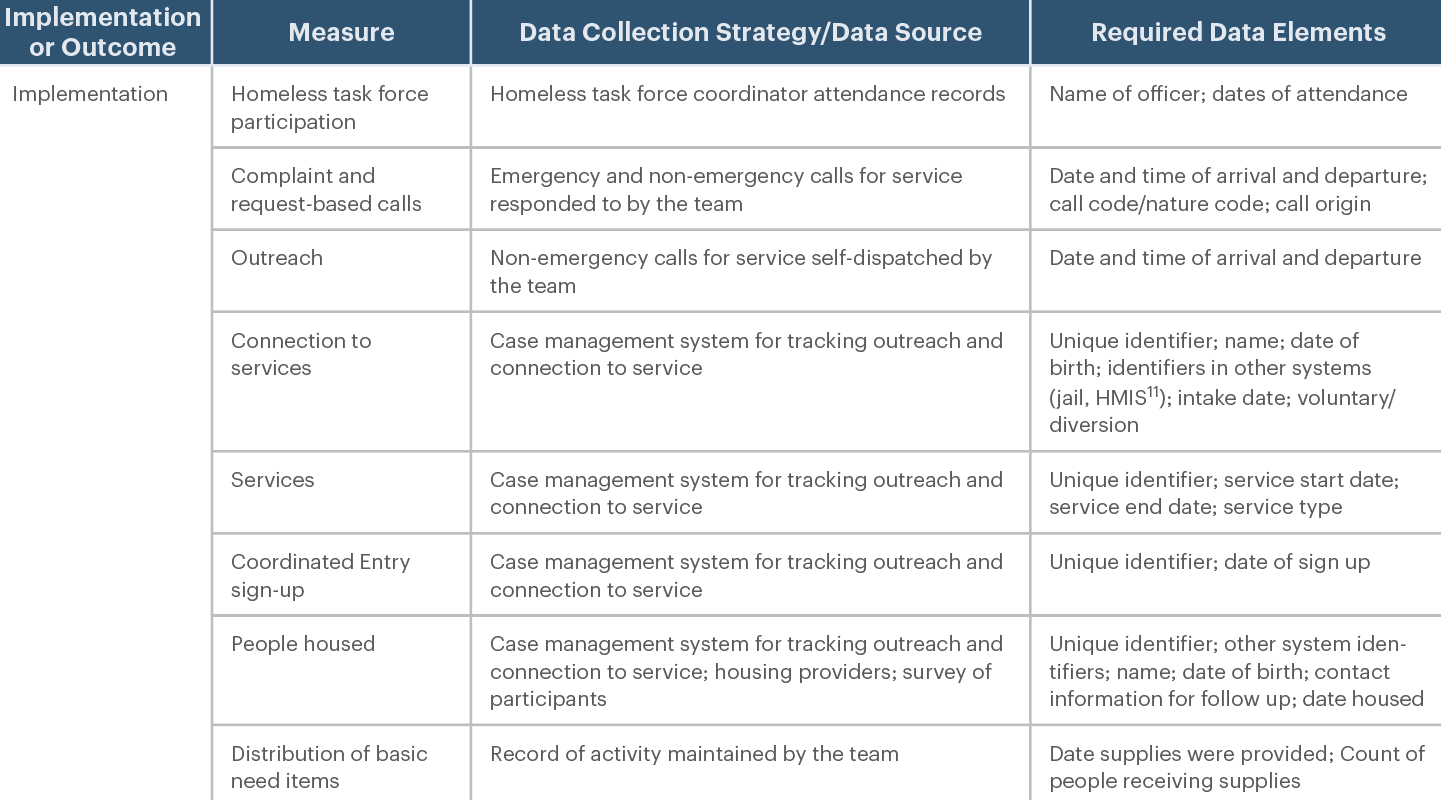

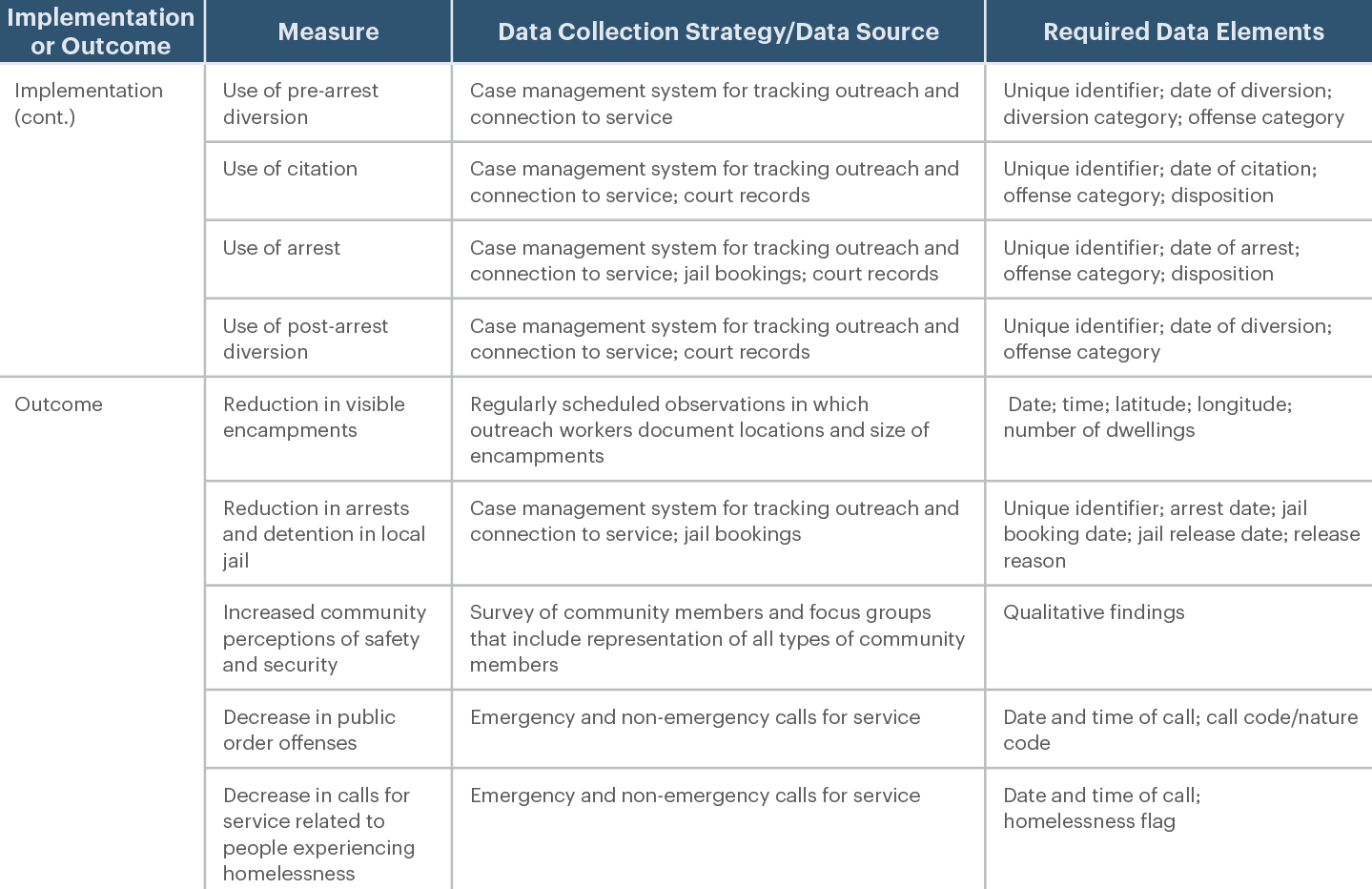

B. Sample Implementation and Outcome Measures

In this example, components of the logic model in Appendix A are translated into metrics using a series of questions to consider.

IMPLEMENTATION MEASURES

Is the law enforcement response team coordinating with the homelessness service system, such as the local or statewide Continuum of Care?

- Homeless task force participation: Number of homeless task force meetings attended by a member of the team

How much of the team’s workload is spent responding to homelessness-related calls compared to outreach?

- Complaint and request-based calls:

- Number of calls responded to by the team

- Number of calls by call code/nature code

- Number of calls by the entity initiating the call (community member complaint; request for assistance by a first responder such as fire, emergency medical services, or crisis worker; request for assistance by a service provider; other)

- Time the team spent on scene (average, median)

- Outreach: Number of officer-initiated contacts related to human needs, access to treatment and services, transportation, and relationship building

- Time the team spent per contact (average, median)

What services are people experiencing homelessness being connected to when they encounter the law enforcement response team?

- Connection to services: Number of people the response team connects to additional health, legal, treatment, nutrition, or employment services (better to count things like warm handoffs, appointments attended, or services delivered directly over brochures distributed or information given)

- Services:

- Number of services initiated with help from the team

- Number of services started by issue (housing, identification, basic needs, treatment, vocational, benefits enrollment, safeguarding during a weather emergency)

- Coordinated Entry sign-ups: Number of intakes into the Coordinated Entry system for access to housing

- Housing: Number of people connected to services by the team who are placed in housing

- Distribution of basic need items: Number of times the team offers food, clothing, equipment, or similar items to provide immediate relief

Is the team using the least restrictive enforcement tactics needed to accomplish public safety goals?

- Use of pre-arrest diversion:

- Number of incidents where a person experiencing homelessness met the criteria for citation or arrest and accepted services as an alternative

- Number of diversions made by type (divert from citation, divert from arrest, other)

- Number of diversions made by offense category of the most severe offense that could be alleged (violent, property, drug, public order, other)

- Use of citation:

- Number of incidents where a person was notified that they must pay a fine or appear in court on an assigned date

- Number of citations given by offense category of the most severe offense that could be alleged (violent, property, drug, public order, other)

- Number of citations given by outcome (fine, diversion, other)

- Use of arrest:

- Number of incidents where a person was taken into custody and booked into jail

- Number of arrests made by offense category of the most severe offense that could be alleged (violent, property, drug, public order, other)

- Number of arrests made by outcome (sentenced to incarceration, sentenced to probation, diversion, other)

- Use of post-arrest diversion:

- Number of incidents where a person experiencing homelessness was cited or arrested and subsequently accepted a diversion opportunity involving coordination or case management with the team

- Number of diversions made by offense category of the most severe offense that could be alleged (violent, property, drug, public order, other)

OUTCOME MEASURES

How do the lives of individuals change?

- Reduction in arrests over time by any law enforcement agency serving the community, and the resulting time in local jail, of people connected to services

- Arrested: Number and percentage of participants with at least one arrest in the following year after first engaging in services

- Number of arrests: Average and median number of arrests per participant in the year after first engaging in services

- Time incarcerated in local jail: Average and median number of days spent in jail per arrest

How does the community change?

- Reduction in visible encampments: Count of the number of encampments visible from the street within the community

- Increased community perceptions of safety and security: Qualitative findings from residents, businesses, and visitors who report they feel safe on streets, public transportation, and in public places like parks and playgrounds in the area targeted by the team

- Decrease in public order offenses: Calls for service related to public intoxication, vagrancy, loitering, trespassing, disorderly conduct, prostitution and related

- Decrease in calls for service about people experiencing homelessness: Calls for service flagged as involving a person experiencing homelessness

Tip: If possible, consider reporting implementation and outcome measures separately for people identified as experiencing chronic homelessness.

C. Sample Data Collection Plan

In this example, a data collection strategy and the required data elements are identified for each measure in Appendix B. For information about privacy considerations related to data collection, see Establishing an Information Sharing Approach.

D. Sample Scope of Work

This is an example of a scope of work that agencies leading a law enforcement response to homelessness can use to engage a research partner. It describes the assessment to be conducted and outlines expectations for the work to be completed.

PROJECT BACKGROUND

The law enforcement agency (Agency) plans to implement a homeless outreach team (HOT) and requests assistance with problem identification and to subsequently understand whether the new response works as intended. The purpose of the new project is to address calls related to substance use, panhandling, camping, and trespassing.

OBJECTIVES

Assessment activities will inform planning and determine the feasibility of completing an outcome evaluation to demonstrate the degree in which project activities have compelled people experiencing homelessness to engage in services; reduced arrests; and increased perceptions of safety and security in the community. Objectives for the assessment activities described are as follows:

- To identify the problem that should be addressed and understand the potential impact of proposed solutions;

- To assess progress toward completing activities as intended during program planning;

- To identify and analyze unintended consequences resulting from the activities as currently implemented;

- To determine whether there is a plausible connection between the activities and the planned desired outcomes;

- To assess the existence and quality of data needed to complete an outcome evaluation and to identify any related concerns about privacy and confidentiality of the necessary data

ASSESSMENT ACTIVITIES

The research partner will use a mixed methods approach to provide a comprehensive understanding of the project and inform recommendations for program planning. Analysis will detail the HOT team’s workload related to responding to calls for service and performing outreach-related activities, the services and resources people experiencing homelessness access as a result of the team’s intervention, and the use of enforcement tactics by the team.

The research partner will collect three years of administrative data related to law enforcement response activities and will document project context and practices by gathering information from key stakeholders such as organizational leaders, program participants, and community members. Data collected for the project will include personally identifiable information, and the research partner will maintain data securely and preserve the confidentiality of the information. Release of information or materials produced through the assessment to outside parties should always be cleared with agency staff. Plans for publishing results should be discussed and agreed upon prior to submitting materials for publication.

To keep project staff informed, the research partner will attend monthly staff meetings and set up regular meetings as required to maintain communication. In addition, the research partner will submit quarterly reports to agency leadership detailing the work performed and the status of assessment activities.

Research partner responsibilities will include:

- Conducting a literature review on practices related to law enforcement responses to homelessness

- Developing an assessment plan informed by program staff input

- Conducting focus groups with staff, partners, and participants

- Establishing and overseeing procedures for ensuring confidentiality and quality of the data

- Developing data collection protocols

- Analyzing administrative and original data to produce program measures

- Producing reports and presenting findings to agency and city leadership

DELIVERABLES, TIMELINE, AND BUDGET

Assessment activities are expected to be completed within one year and should document the important findings, conclusions, and recommendations to be presented to agency leadership and elected officials. The total project fee for the scope of work outlined will be paid in four equal installments. Payments will be tied to the successful completion of key project milestones as follows:

- Phase 1: Assessment planning, document review, literature review

- Phase 2: Data collection

- Phase 3: Data cleaning and analysis

- Phase 4: Report and presentation development

Endnotes

1. Office of Policy Development and Research, Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (Office of Policy Development and Research, December 2024), https://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/ahar/2024-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us.html.

2. “Definition of Chronic Homelessness,” HUD Exchange, accessed May 14, 2025, https://www.hudexchange.info/homelessness-assistance/coc-esg-virtual-binders/coc-esg-homeless-eligibility/definition-of-chronic-homelessness/.

3. Amy Howe, “Court Divided Over Constitutionality of Criminal Penalties for Homelessness,” Scotus Blog, April 22, 2024, accessed April 5, 2025, https://www.scotusblog.com/2024/04/court-divided-over-constitutionali-ty-of-criminal-penalties-for-homelessness/.

4. Supreme Court of the United States, Syllabus: City of Grants Pass, Oregon Johnson et al. (Supreme Court of the United States, June 2024), https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/23-175_19m2.pdf.

5. Natalie Hipple et , “Police Responses to People Experiencing Homelessness,” Police Quarterly (2024), https://doi.org/10.1177/10986111241289390.

6. Ibid.

7. Mary Cunningham et al., Breaking the Homelessness-Jail Cycle with Housing First: Results from the Denver Supportive Housing Social Impact Bond Initiative (The Urban Institute, 2021), https://urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104501/breaking-the-homelessness-jail-cycle-with-housing-first_1.pdf.

8. Margot Kushel, et al., “Toward a New Understanding: The California Statewide Study of People Experiencing Homelessness” (San Francisco: University of California Benioff Homelessness and Housing Initiative, 2023), https://homelessness.ucsf.edu/our-impact/studies/california-statewide-study-people-experiencing-homelessness.

9. United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, Core Elements of Effective Street Outreach to People Experiencing Homelessness (United States Interagency Council on Homelessness, June 2019), https://usich.gov/sites/default/files/document/Core-Components-of-Outreach-2019.pdf.

10. The Annie E. Casey Foundation, Developing a Theory of Change: Practical Guidance (The Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2022), https://www.aecf.org/resources/theory-of-change.

11. “HMIS is a local information technology system used to collect client-level data and data on the provision of housing and services to individuals and families at risk of and experiencing homelessness,” See “HMIS: Homeless Management Information System,” HUD Exchange, accessed June 16, 2025, https://www.hudex- info/programs/hmis/.

Photo Credit: Ernie Stevens, CSG Justice Center

This project was supported by Grant No. 15PNIJ-21-GG-02709-RESS, awarded by the National Institute of Justice, which is a component of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs. The Office of Justice Programs also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the Bureau of Justice Assistance, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of views or opinions in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice or The Council of State Governments.

Project Credits

Writing: Emily Rogers and Katie Holihen, CSG Justice Center

Research: Dr. Kayla Allison, University of Arkansas, and Dr. Natalie Hipple, Indiana University

Advising: Hallie Fader-Towe and Dr. Jessica Saunders, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Darby Baham, CSG Justice Center

Design: Stephanie Northern, The Council of State Governments

Web Development: Caroline Cournoyer, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Sarah Kelley, CSG Justice Center

Back to Top of Publication.

The CSG Justice Center Advisory Board establishes the policy and project priorities of the organization. The board features…

Read More Breaking the Cycle of Homelessness and Incarceration: Q&A with New CSG Justice Center Advisory Board Member Wayne Niederhauser

Breaking the Cycle of Homelessness and Incarceration: Q&A with New CSG Justice Center Advisory Board Member Wayne Niederhauser

The CSG Justice Center Advisory Board establishes the policy and project priorities…

Read More