Building Connections to Housing During Reentry

Results from a Questionnaire on DOC Housing Policies, Programs, and Needs

Securing stable, affordable housing is fundamental to successful reentry. To help policymakers build sustainable pathways to housing, The Council of State Governments Justice Center, in partnership with the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs’ Bureau of Justice Assistance, conducted the first national survey of state Departments of Corrections reentry coordinators, receiving responses from 37 out of 50 states plus the District of Columbia. This national report outlines current practices, highlighting areas where policymakers can direct efforts to increase connections to housing.

Building Connections to Housing During Reentry

Results from a Questionnaire on DOC Housing Policies, Programs, and Needs

Introduction

Access to stable, affordable housing is vital to successful reentry, helping to reduce returns to prison and jail and strengthen a number of other positive outcomes.¹ However, people who have histories of incarceration often face significant challenges to obtaining housing at release.² State Departments of Correction (DOCs) are well-positioned to address these challenges and improve access to post-release housing due to their central role in discharge and reentry planning, but reentry coordinators within these agencies may not always have the information and partnerships they need to effectively do so. However, by integrating needs assessments and connections to housing into reentry planning processes, DOCs can help mitigate some of the most difficult housing barriers faced by people in reentry and provide for better overall outcomes.

Building on this understanding of the key role of DOCs in reentry housing, The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center conducted a housing questionnaire among DOC reentry coordinators in spring 2022 on behalf of the U.S Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs’ Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The goal of this questionnaire was to better understand the current landscape of DOC reentry housing policies and programs in order to better support DOCs as they work to assist people at risk of homelessness reenter the community from prison. This report summarizes the key findings and policy implications of the questionnaire in the following areas:

- Screening and assessment to understand risk of homelessness and housing needs, as well as policies regarding post-release addresses;

- Collaboration among criminal justice and housing/homelessness and other community services;

- Post-release housing and supports provided by DOCs; and

- Existing reentry housing barriers and gaps.

To view the executive summary of this report, visit Building Connections to Housing During Reentry: Results from a Questionnaire on DOC Housing Policies, Programs, and Needs on the CSG Justice Center website and select Executive Summary.

Methodology

In April 2022, the CSG Justice Center developed a SurveyMonkey questionnaire for DOC reentry coordinators featuring questions in four topical areas: (1) screening and assessment practices and post-release address policies, (2) cross-system partnerships, (3) housing programs provided and funded by DOCs, and (4) reentry housing gaps and needs. The questionnaire included 26 questions in total, with a combination of multiple choice and narrative response items. CSG Justice Center staff distributed the questionnaire via email to reentry coordinators from all 50 states and the District of Columbia and provided multiple response reminders over the course of approximately six weeks. After this six-week period, responses were received from 37 states and used to develop this report.³

Findings

Finding 1.

Nearly all responding DOCs indicated that they ask people questions about their housing needs as part of the discharge/reentry planning process. For almost half, if housing is not identified prior to release, people must remain incarcerated until an address is approved.

Understanding someone’s housing needs as they are preparing for reentry is an essential first step to connecting people with housing. It also helps prioritize people with the highest needs for housing and supportive service resources, which are often limited. Ideally, this planning process includes both housing needs assessments, which are questions designed to determine the type of reentry housing that best meets a person’s needs, as well as homelessness screenings—questions designed to assess for a history of homelessness and/or risk of homelessness at release. These screenings and assessments may be integrated or separate depending on DOC staffing and workflows.

Screening and Assessment Practices and Methods

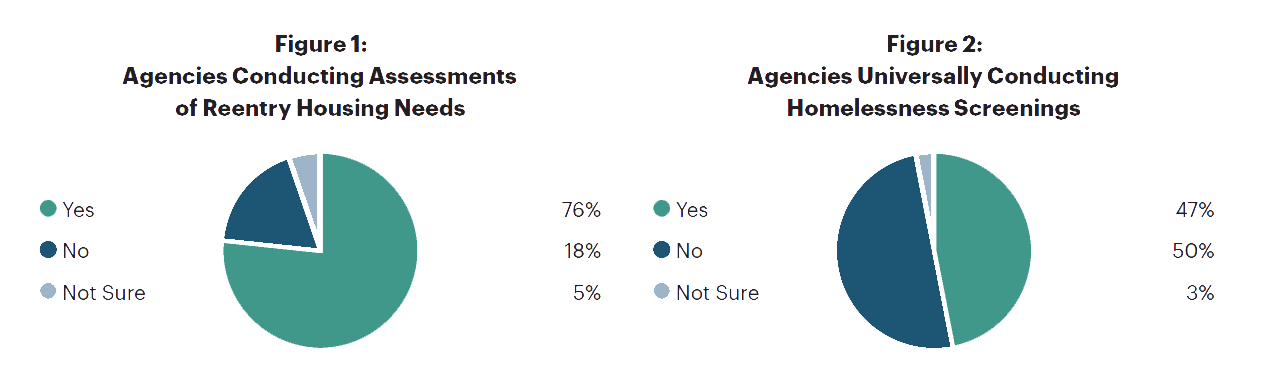

The majority of responding DOCs (76 percent) said that they conduct housing needs assessments in order to facilitate effective reentry planning. A smaller number (47 percent) indicated that they also conduct homeless screenings for all residents.

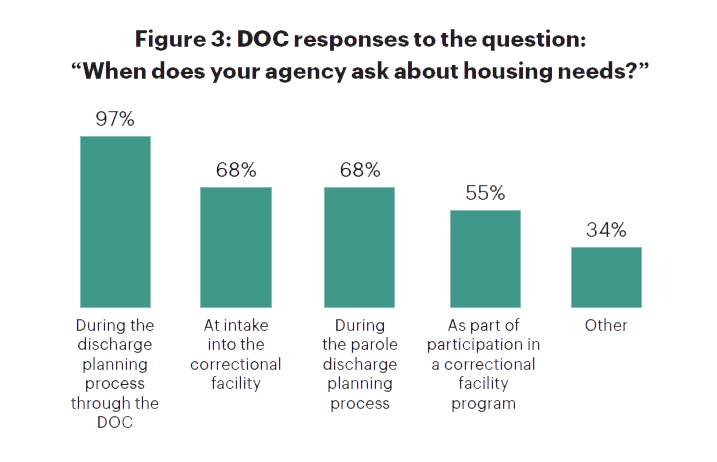

Nearly all responding DOCs (97 percent) noted that they ask people housing-related questions (e.g., any history of homelessness, housing needs, likely post-release address, etc.) during the discharge planning process, while a smaller but still significant number (68 percent) ask these questions during intake. In narrative responses, several DOCs shared that they learn whether someone has experienced homelessness prior to intake through the court’s pre-sentencing reports.

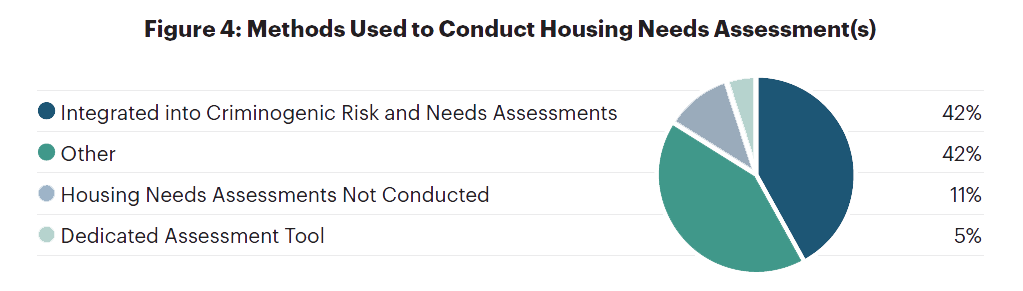

The tools responding DOCs use to conduct housing needs assessments vary considerably and include commonly used tools such as the Justice Discharge Vulnerability Index Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (JD-VI-SPDAT)4 and other locally created forms. Close to half of respondents (42 percent) indicated that they integrate a housing needs assessment into their criminogenic risk and needs assessment tools. However, only 5 percent indicated that they have a dedicated tool for assessing housing and/or service needs.

Post-Release Address Policies

Nearly half of responding DOCs (47 percent) stated that they require people to remain incarcerated until a specific address has been identified. However, most responding agencies also indicated that people may be released into shared living arrangements with family members (84 percent) or temporary arrangements such as shelters (79 percent). In narrative responses, several DOCs clarified that these release decisions are governed by the amount of time remaining on a person’s sentence. Specifically, if a person is being released to community supervision, responding agencies typically must approve and/or verify a post release address, but if a person has reached the maximum time on their sentence, these requirements do not apply.

Finding 2.

Most responding DOCs reported that they actively engage in cross-system partnerships, although these engagements are typically with criminal justice system-led planning bodies. DOCs also noted that they partner with a range of housing agencies, with a majority indicating they mostly work with providers of transitional/recovery and supportive housing.

Given the multiple barriers to housing that people face during reentry,5 DOC partnerships with other systems— particularly the housing and health/behavioral health care systems—can provide vital resources to help build and sustain successful housing connections. In addition, these systems often serve a shared population who access their services. Therefore, collaborations can help both maximize limited resources and improve outcomes for people. Continuums of Care (CoCs)6 and Public Housing Authorities (PHAs), for example, are generally the largest sources of homeless assistance funding and support in many communities, making them vital partners in efforts to expand reentry housing opportunities.

Cross-System Partnerships Reported by DOCs

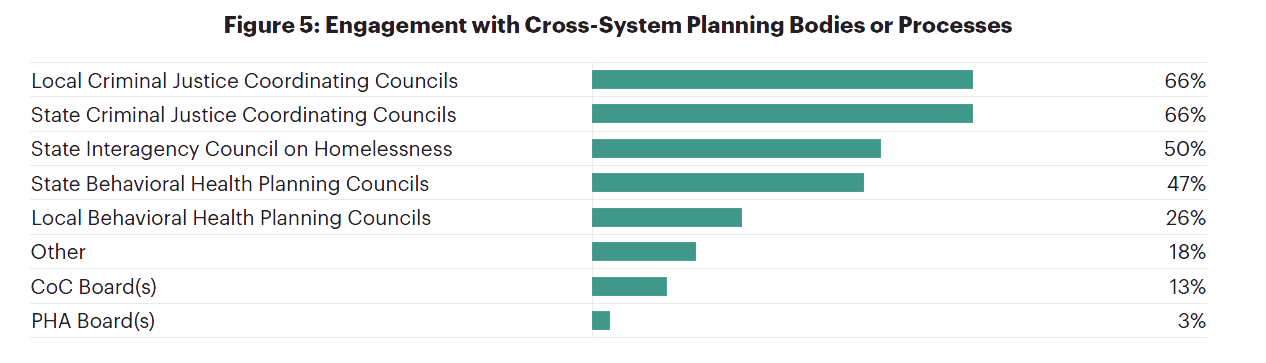

Responding DOCs reported engagement with a range of state and/or local planning bodies representing criminal justice and key partner systems (including housing, health/behavioral health, etc.). Not surprisingly, the most commonly reported engagement (66 percent) was with state and local criminal justice coordinating councils. However, significant numbers also reported engagement with state-level bodies from other systems, including interagency councils on homelessness and behavioral health planning groups. By contrast, few DOCs reported engagement with CoC or PHA boards; narrative responses suggested that one reason may be the lack of established working relationships.

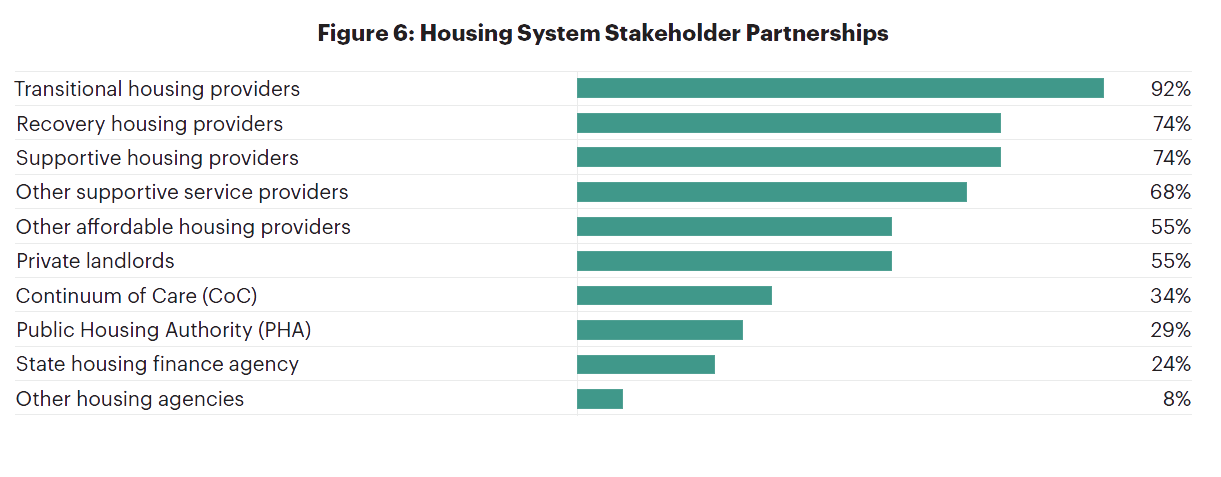

Most responding DOCs indicated maintaining active communication and collaboration with housing partners, although most often with transitional7 (92 percent) and recovery housing8 providers (74 percent). These relationships are most prevalent likely due to the fact that historically, locating permanent housing has not fit within the core DOC focus of custodial care. However, many responding DOCs still reported collaborations with supportive housing (74 percent) and other supportive service (68 percent) providers, perhaps because many people in the justice system are likely to have needs for both long-term housing assistance and supports for complex care and other needs.9 In addition, more than half of respondents (55 percent each) indicated they partner with private landlords, as well as other affordable housing providers (for example, privately owned subsidized housing), potentially in recognition of a need for more permanent housing connections. However, as mentioned earlier, engagement with local affordable housing system partners, including CoCs and PHAs, was much less common.

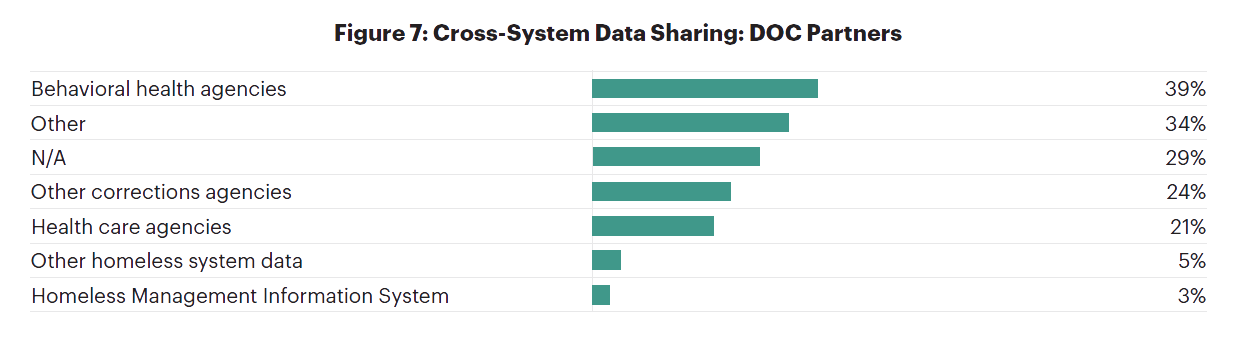

Finally, regarding data sharing, responding DOCs reported that they most typically share information with behavioral health providers (39 percent), potentially due to established partnerships and the need for care coordination. However, very few DOCs (less than 5 percent) indicated sharing data with housing partners, and almost a third of respondents shared that they do not share data with any outside agencies.

Finding 3.

A majority of responding DOCs indicated that they provide at least one type of post-release housing assistance, but it is typically short-term. Most DOCs also reported providing case management and housing search/navigation assistance.

Housing needs during the reentry process generally include both a short- and a long-term component. Time-limited interventions such as short-term rental assistance or transitional housing help meet immediate needs for safety and stability after release, while long-term resources, such as permanent supportive housing10 or other subsidized housing, help ensure ultimate success in the reentry process. As noted earlier, many DOCs do not typically include within their mission to provide long-term housing assistance, and the budgetary demands to do so can be significant. Therefore, strong housing system partnerships are critical to help ensure long-term or permanent housing is attainable on a state or community level. However, DOCs can still play an important role in meeting short-term needs to find and help people afford and maintain housing.

Analysis of Housing and Supportive Services Provided by DOCs

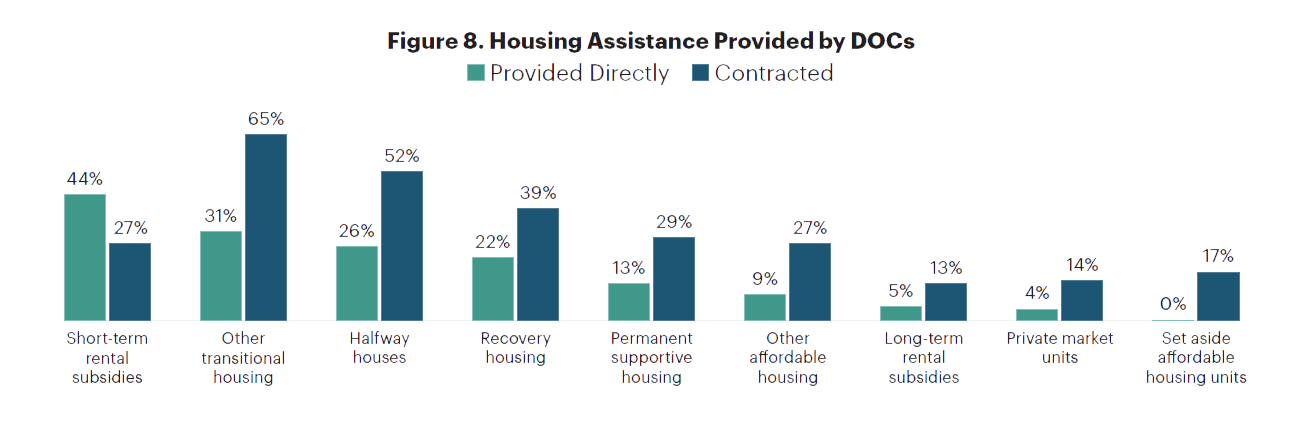

The majority of responding DOCs (71 percent) indicated that they provide at least one type of post-release housing assistance. However, whether provided directly by the DOC or via contract, these options are typically short-term in nature. Indeed, more than half of DOCs indicated that they contract for transitional housing (65 percent) or halfway house (52 percent) services. Responding DOCs were less likely to provide housing assistance directly, but nearly half (44 percent) indicated that they directly provide some form of short-term rental assistance, such as financial assistance to private landlord partners or support for hotel stays. By contrast, direct provision or contracting for long-term housing options, such as permanent supportive housing or long-term rental assistance, is much less common. Responding DOCs indicated that connections with these services are typically accomplished via referrals to outside providers. For example, in the case of permanent supportive housing, nearly 90 percent of DOCs make referrals in an effort to connect people to this service, whether to the housing agencies themselves or to intermediaries such as CoCs.

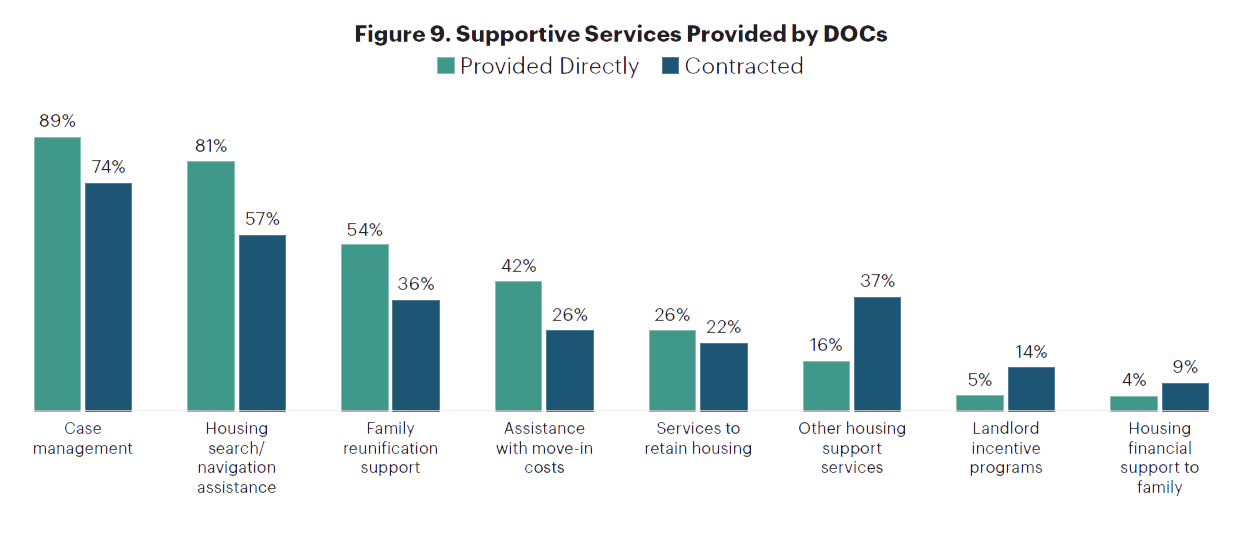

The housing support services that are most commonly provided directly by responding DOCs are case management (89 percent) and housing search/navigation assistance (81 percent)—both core functions to help build reentry housing connections. This type of support is the most cost-effective option for many departments since it is typically performed by reentry coordinators, housing specialists, or case managers. However, more than half of respondents indicated that they contract for these services as well. Though less common, responding DOCs also indicated directly providing a range of other support services that can impact housing options and reentry success, including family reunification support (54 percent) and assistance with move-in costs (42 percent).

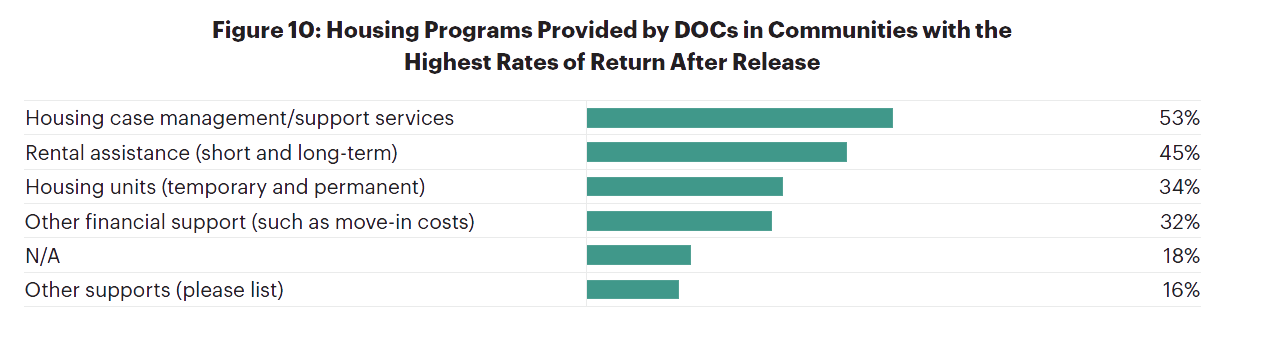

To maximize limited resources and increase impact, many responding DOCs reported focusing reentry housing efforts on the areas of their states to which people most frequently return after release. In these areas, responding DOCs most commonly provide housing case management/support services (53 percent) and short and long-term rental assistance (45 percent) to people reentering the community.

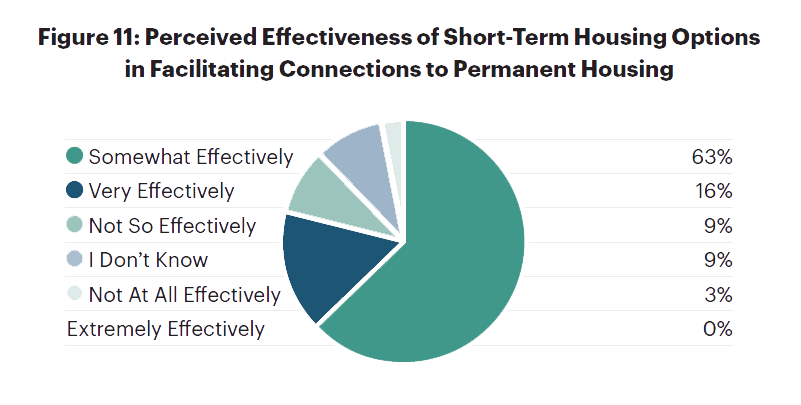

Finally, while the questionnaire results show that many DOCs are providing at least some level of housing assistance, a majority of responding DOCs (63 percent) reported that they found the interim housing options that they provide (such as short-term rental assistance or transitional housing) to be only somewhat effective in leading to permanent housing. Only 16 percent found them to be very effective. The reasons behind this dynamic are likely due to the many barriers to long-term housing success faced by people in reentry, detailed further in the following section.

Finding 4.

Responding DOCs reported that the most common barriers to housing placements are lack of affordable housing options, discrimination/stigma based on criminal justice history or record, and restrictive housing provider and landlord policies, in addition to widely reported gaps in supportive and permanent housing.

Affordable housing is in short supply in much of the U.S., with a current national shortage of 7 million units.11 People in reentry often face significant challenges in accessing the limited housing that is available for a number of reasons, most notably widespread stigma and discrimination and policy barriers imposed by housing providers. These can include eligibility disqualifications by PHAs or other subsidized housing providers12 for relatively minor offenses or those that occurred many years in the past. In addition, these challenges exacerbate the already significant racial and ethnic disparities among people experiencing both homelessness and incarceration.13 DOC initiatives to provide connections to housing can be an important tool to help mitigate these barriers during the early days of the reentry process.

Analysis of Barriers and Gaps Reported by DOCs

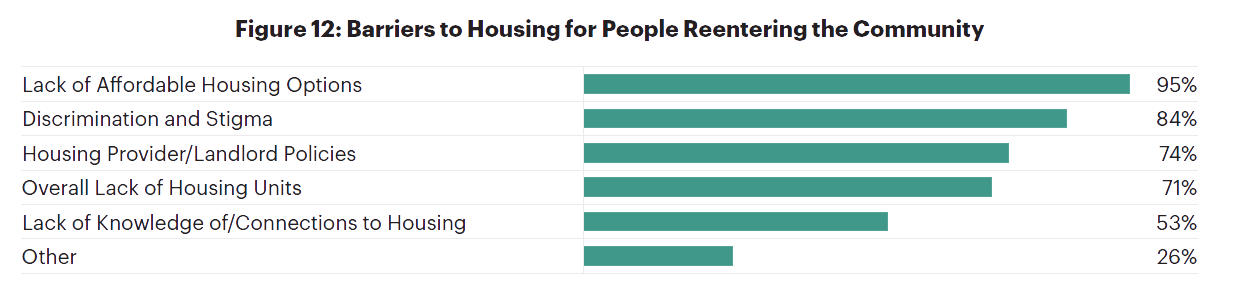

Responding DOCs reported a number of barriers to housing for people reentering the community, but lack of affordable housing options (95 percent), discrimination and stigma (84 percent), and restrictive housing provider/ landlord policies (74 percent) were the most prevalent. Narrative responses also highlighted a lack of knowledge among corrections staff about available housing options, and many respondents said that people with sex offense records or people with behavioral health needs are more challenging to place in housing. In addition, a majority of responding DOCs (42 percent) noted that they did not notice any racial or ethnic disparities in post-release housing success. However, narrative responses indicated this trend may be due to a lack of widespread data collection in this area, and not because these are not barriers that need to be considered.

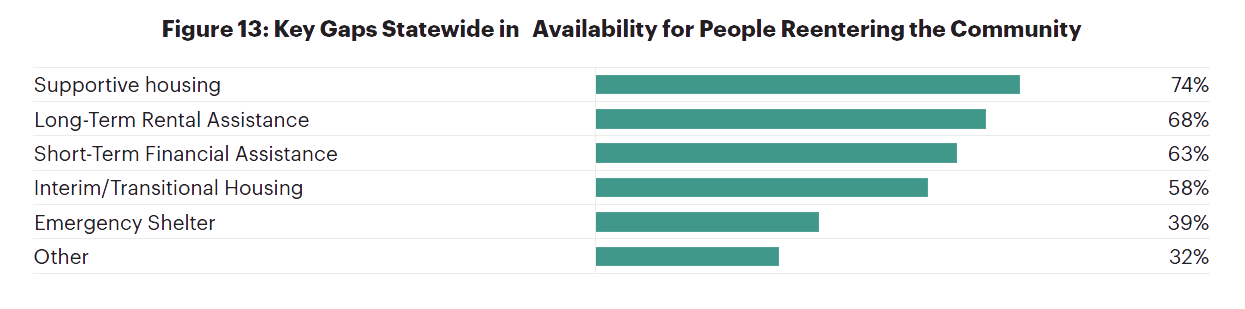

Responding DOCs reported gaps in availability across many statewide housing options, with long-term options being the most prevalent, particularly housing with supportive services (74 percent) and long-term rental assistance (68 percent). These findings are consistent with national data on the general scarcity of affordable housing. Narrative responses continued to highlight the lack of housing for people with sex offense convictions and mental health needs as major additional gaps, in addition to the general fragmentation among available housing and supportive service resources.

Next Steps: Policy and Program Needs Identified by DOCs

Participating DOCs shared a range of policies and programs they would like to implement to more effectively connect people with housing at reentry. Of particular focus were increasing access to long-term housing options, improving working relationships with community partners, and more effectively supporting DOC reentry housing programs.

Many responding DOCs noted the need for increased access to long-term housing options, such as housing vouchers and permanent supportive housing. Respondents noted that many individuals need support beyond short-term solutions, and their departments would have increased reentry success if longer-term options were available. They suggested strengthening collaborations with housing agencies to increase access to these resources. Several agencies also noted a particular need for supportive reentry housing for people with mental health needs, and for more housing options for people with sex offense convictions, who are particularly difficult to house due to restrictions related to where they can live and who they can be housed with, as well as community opposition.

Responding DOCs also noted that they would like their agency to work more effectively with community partners in identifying people in need and connecting them to housing. In this area, a number of DOCs identified a need for increased support for landlords serving the reentry population, including both education/outreach as well as financial incentives. In addition, DOCs also made a number of other suggestions to improve these connections, including increased engagement with housing agency boards and behavioral/public health agencies, increasing transitional case management services, and expansion of local reentry councils.

Finally, DOC reentry coordinators also reported a need for increased financial and organizational support for reentry housing programs. Several respondents emphasized the need to identify and secure sustainable funding streams for this work, as well as more staff to support housing coordination. Other respondents highlighted the need for better case management and improved workflows within their organization, noting that there was an overall lack of knowledge of what services may be available. Finally, some respondents also shared a desire to implement a formalized housing needs assessment to be able to better match people with their appropriate housing needs.

To meet these significant identified needs to connect people leaving prison and jail to housing, one of the most important strategies for DOCs is to draw on a diverse range of funding sources—including federal resources such as Medicaid and non-federal sources such as state line-item funding. In addition, since DOCs are typically not able to fund or sustain permanent housing programs, ongoing engagement and partnership with housing providers is another central strategy. These efforts will ensure that people in reentry are prioritized for these resources and help to promote ongoing community efforts to expand overall housing supply.

Appendix

CSG Justice Center Resources on Key Reentry Housing Topics.

Housing Screening and Assessment:

The CSG Justice Center, Assessing Housing Needs and Risks: A Screening Questionnaire (New York: CSG Justice Center, 2022), https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/assessing-housing-needs-and-risksa-screening-questionnaire/.

The CSG Justice Center and The Council on Criminal Justice and Behavioral Health, “California Webinar Series: Common Practices for Connecting to and Using Housing as a Diversion and Reentry Strategy,” (webinar, CSG Justice Center, New York, February 24, 2022), https://csgjusticecenter.org/events/common-practices-for-connecting-to-and-using-housing-as-a-diversion-and-reentry-strategy/.

The CSG Justice Center and Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), “The Role of Housing Supports in Reentry,” (webinar, CSG Justice Center, New York, April 27, 2021), https://csgjusticecenter.org/events/the-role-of-housing-supports-in-reentry/.

The Role of Cross-System Partnerships in Reentry:

Charles Francis, Action Points: Four Steps to Expand Access to Housing for People in the Justice System with Behavioral Health Needs (New York: CSG Justice Center, 2021), https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/action-points-2/.

Charles Francis and Joseph Hayashi, “Explainer: Building Effective Partnerships with Continuums of Care to Increase Housing Options for People Leaving Prisons and Jails,” CSG Justice Center, March 21, 2022, https://csgjusticecenter.org/2022/03/21/explainer-building-effective-partnerships-with-continuums-of-care-to-increase-housing-options-for-people-leaving-prisons-and-jails/.

Charles Francis and Stephanie Joson, “How States are Engaging Private Landlords–an Untapped Resource in Reentry Housing,” CSG Justice Center, October 15, 2021, https://csgjusticecenter.org/2021/10/15/how-states-are-engaging-private-landlords-an-untapped-resource-in-reentry-housing/.

Thomas Coyne, The Role of Probation and Parole in Making Housing a Priority for People with Behavioral Health Needs (New York: CSG Justice Center, 2021), https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/the-role-of-probation-and-parole-in-making-housing-a-priority-for-people-with-behavioral-health-needs/.

Developing and Implementing Successful Reentry Housing Interventions:

The CSG Justice Center and BJA, “How State-Led Housing Initiatives Can Break the Cycle of Criminal Justice Involvement,” (webinar, CSG Justice Center, New York, September 23, 2020), https://csgjusticecenter.org/events/how-state-led-housing-initiatives-can-break-the-cycle-of-criminal-justice-involvement/.

The CSG Justice Center, BJA, and Corporation for Supportive Housing, “Thinking Outside the Box Webinar Series,” (webinar, CSG Justice Center, New York, May 19, 2022), https://csgjusticecenter.org/events/the-action-points-framework-four-key-steps-to-expanding-housing-opportunities/.

The CSG Justice Center, the National Reentry Resource Center, and BJA, “Using American Rescue Plan and CARES Act Housing Resources to Support Reentry: HUD and Community Perspectives,” (webinar, CSG Justice Center, New York, April 20, 2022), https://csgjusticecenter.org/events/using-american-rescue-plan-and-cares-act-housing-resources-to-support-reentry-hud-and-community-perspectives/.

Thomas Coyne, “Explainer: Creating Housing Opportunities for People with Complex Health Needs Leaving Incarceration,” CSG Justice Center, September 8, 2021, https://csgjusticecenter.org/2022/09/08/explainer-creating-housing-opportunities-for-people-with-complex-health-needs-leaving-incarceration/.

Barriers to Reentry Housing:

Charles Francis, Thomas Coyne, and Katie Herman, Reducing Homelessness for People with Behavioral Health Needs Leaving Prisons and Jails: Recommendations to California’s Council on Criminal Justice and Behavioral Health (New York: CSG Justice Center, 2021), https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/reducing-homelessness-for-people-with-behavioral-health-needs-leaving-prisons-and-jails/.

“National Inventory of Collateral Consequences of Conviction,” CSG Justice Center, accessed September 22, 2022, https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/the-national-inventory-of-collateral-consequences-of-conviction/.

Footnotes

1. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Permanent Supportive Housing: Evaluating the Evidence for Improving Health Outcomes Among People Experiencing Chronic Homelessness.

2. Danya E. Keene, Amy B. Smoyer, and Kim M. Blankenship, “Stigma, Housing, and Identity After Prison,” The Sociological Review 66, no. 4 (2018): 799–815, https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026118777447.

3. Responses were received from the following states: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

4. OrgCode Consulting Inc. and Community Solutions, Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (SPDAT) Manual (Oakville, ON: OrgCode Consulting, 2015), https://cceh.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/SPDAT-v4.0-Manual.pdf.

5. Keene, Smoyer, and Blankenship, “Stigma, Housing, and Identity After Prison,” 799-815.

6. A CoC is a local/regional planning entity that receives homeless assistance funding for housing and supportive services from HUD. They are located in nearly every community in the U.S, and their key responsibilities include prioritizing housing and service projects for HUD funding as well as coordinating housing and shelter placements. See Charles Francis and Joseph Hayashi, “Explainer: Building Effective Partnerships with Continuums of Care to Increase Housing Options for People Leaving Prisons and Jails,” CSG Justice Center, March 21, 2022, https://csgjusticecenter.org/2022/03/21/explainer-building-effective-partnerships-with-continuums-of-care-to-increase-housing-options-for-people-leaving-prisons-and-jails/.

7. Transitional housing is a short-term housing option that helps fill immediate inventory gaps and is often used for people moving from an institutional setting into the community.

8. Recovery housing is a specialized housing option designed to serve as a resource for people who voluntarily choose a specialized substance-free environment as part of their treatment or to meet conditions of release.

9.Lucius Couloute, Nowhere to Go: Homelessness Among Formerly Incarcerated People (Northampton, Massachusetts: Prison Policy Institute, 2018), https://www.prisonpolicy.org/reports/housing.html; Greg Greenberg and Robert Rosenheck, “Jail Incarceration, Homelessness, and Mental Health: A National Study,” Psychiatric Services 59, no. 2 (2008): 170–177, https://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdfplus/10.1176/ps.2008.59.2.170.

10. Permanent supportive housing provides subsidized housing coupled with tenant-driven, wraparound services, and is typically prioritized for people with the highest needs for behavioral health and other supports.

11. National Low Income Housing Coalition, The Gap: A Shortage of Affordable Rental Homes (Washington, DC: National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2022).

12. HUD has recently been increasing its focus in this area; Secretary Marcia Fudge instructed every HUD program office to review and propose changes to all relevant regulations and guidance documents within six months in a comprehensive effort to reduce barriers to participation for people with criminal records. See Marcia L Fudge, “Eliminating Barriers that Many Unnecessarily Prevent Individuals with Criminal Histories from Participating in HUD Programs,” Memorandum to HUD Principal Staff, April 12, 2022, accessed September 28, 2022, https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/Main/documents/Memo_on_Criminal_Records.pdf.

13. Couloute, Nowhere to Go: Homelessness Among Formerly Incarcerated People.

Project Credits

Writing: Charles Francis, Joseph Hayashi, and Alexandria Hawkins, CSG Justice Center

Research: Charles Francis, CSG Justice Center

Advising: Hallie Fader-Towe and Sarah Wurzburg, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Darby Baham, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Public Affairs: Sarah Kelley, CSG Justice Center

Web Development: Catherine Allary

This project was supported by Grant No. 2020-CZ-BX-K001 awarded by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs’ Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA). BJA is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice or the Council of State Governments.

Suggested Citation: Charles Francis, Joseph Hayashi, and Alexandria Hawkins, Building Connections to Housing During Reentry: Results from a Questionnaire on DOC Housing Policies, Programs, and Needs (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2023).

About the authors

When returning to their communities from criminal justice settings, people with behavioral health needs face barriers in accessing…

Read MoreNew Hampshire Department of Corrections Commissioner Helen Hanks presents at the Medicaid and Corrections Policy Academy in-person meeting.

Read MoreThe Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center has launched the Collaborating for Youth and Public Safety Initiative…

Read More Assigned to the Cloud Crew: The National Incarceration Association’s Hybrid Case Management for People with Behavioral Health Needs

Assigned to the Cloud Crew: The National Incarceration Association’s Hybrid Case Management for People with Behavioral Health Needs

When returning to their communities from criminal justice settings, people with behavioral…

Read More Meet the Medicaid and Corrections Policy Academy Mentor States

Meet the Medicaid and Corrections Policy Academy Mentor States

New Hampshire Department of Corrections Commissioner Helen Hanks presents at the Medicaid…

Read More Six States Commit to Improving Statewide Strategies to Address Youth Crime, Violence and Behavioral Health

Six States Commit to Improving Statewide Strategies to Address Youth Crime, Violence and Behavioral Health

The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center has launched the Collaborating…

Read More Bipartisan Group of 88 Lawmakers Push for Continued Funding for Reentry and Recidivism Programs

Bipartisan Group of 88 Lawmakers Push for Continued Funding for Reentry and Recidivism Programs

A bipartisan group of 88 lawmakers, led by Representatives Carol Miller (R-WV)…

Read More