Community-Driven Crisis Response: A Workbook for Coordinators

Community-Driven Crisis Response: A Workbook for Coordinators

This workbook contains worksheets, charts, discussion questions, and relevant resources for planning team coordinators to guide their team’s work and vision for launching a community-driven crisis response system.

Introduction

This workbook is designed to help planning team coordinators facilitate their community’s crisis response planning and implementation process. Aligned with Expanding First Response: A Toolkit for Community Responder Programs, this workbook is divided into eight sections that address key issues that are crucial to the success of a community-driven crisis response system. Planning team coordinators can use the worksheets, charts, discussion questions, and relevant resources in this workbook to guide their team’s work and vision for launching a community-driven crisis response system.

1: Community Engagement and Collaboration with Key Stakeholders

Building a planning team for decision-making and managing day-to-day operations is critical for effective planning that addresses the needs of your community. It is imperative that the team not only reflects the demographics of the community but also represents voices of firsthand experience with the criminal justice and behavioral health systems.

Worksheet: List of Planning Team Members

Planning Team Coordinator:

| Name | Title | Organization/Affiliation/Expertise |

Formal Role (if applicable) |

| 1.

|

|||

| 2. | |||

| 3. | |||

| 4. | |||

| 5. |

|

||

| 6. | |||

| 7. | |||

| 8. | |||

| 9. | |||

| 10. |

Questions to Consider:

- Are participating community members a diverse representation of your community?

- How will you ensure that the community members most impacted by the criminal justice and behavioral health systems remain engaged in planning team functions over the long term?

- How often are community, stakeholder, and partner meetings held?

- How will you determine priorities for the planning team?

- How is feedback solicited from the community and other stakeholders? What are the plans for incorporating this feedback into your community-driven crisis response system?

- Describe your plan for informing the public about the rationale for a community-driven crisis response.

2: Needs Assessment

Building a robust crisis response system starts with identifying what your community has in place, pinpointing gaps, and projecting capacity needs for fully scaled responses that adequately match the level of need.

Worksheet: Crisis System Inventory

Consider the work your community is doing on system-wide crisis response as you fill in this chart. The list below was designed to be comprehensive, but please add any other programs/services you have in place and indicate if a specific process allows for improved responses to divert people from the justice system (e.g., information-sharing agreements between justice and behavioral health agencies that allow for expedited connections to crisis care instead of criminal justice involvement).

| Program/Service | Implemented? | Supporting Data Available? | What Are the Short- and Long-Range Goals of the Program/Service? | Funding Options Available? | Notes |

| Public Service Announcements/ Public Awareness Campaigns |

Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No | ||

| Crisis Call Center

a. Staffed 24/7/365 b. Uses another number besides 911 (such as 211 or 311)

|

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No |

a.

b. |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No |

a.

b. |

| Warm Lines

|

Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No | ||

| Outreach/Prevention

a. Homelessness Prevention/Homeless Outreach Team b. Outreach or prevention for people w/ serious mental illnesses and/or substance use disorders who are “familiar faces”¹ c. Opioid Response Teams d. Coordination with Post-Conviction Supervision (Forensic Assertive Community Treatment [FACT] or Assertive Community Treatment [ACT])

|

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No |

a.

b. c. d. |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No |

a.

b. c. d. |

| 911 Dispatch/Call Center Practices

a. Screen calls for behavioral health (BH) need b. Assess risk of suicide c. Divert calls to BH provider d. Dispatch Crisis Intervention Team officer/co-responder e. Embedded clinician at dispatch

|

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No e. Yes/No |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No e. Yes/No |

a.

b. c. d. e. |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No e. Yes/No |

a.

b. c. d. e. |

| 988

|

Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No | ||

| Community Responder Team a. Self-dispatchb. Dispatched through a local crisis response providerc. Dispatched through a local law enforcement agencyd. Dispatched through a local fire departmente. Directly dispatched from an emergency call center (e.g., 911, 988, crisis line)f. Directly dispatched from a non-emergency call center (e.g., 211, 311) |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No e. Yes/No f. Yes/No |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No e. Yes/No f. Yes/No |

a.

b. c. d. e. f. |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No e. Yes/No f. Yes/No |

|

| Co-responder (First Responder and Clinician)

a. Separately dispatched b. Dispatched together c. Call for clinician to scene d. Mobile/virtual response

|

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No

|

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No

|

a.

b. c. d.

|

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No

|

a.

b. c. d.

|

| Services Provided by Co-responder

a. On-scene intervention b. Referral or transport to services/diversion c. Follow-up provided |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No

|

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No

|

a.

b. c.

|

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No

|

a.

b. c.

|

| Emergency Department Diversion

|

Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No | ||

| Mobile Crisis

|

Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No | ||

| Naloxone Plus

|

Yes/No | Yes/No | Yes/No | ||

| Self-Referral to Fire or Law Enforcement

|

Yes/No | Yes/No | |||

| LEAD (Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion/Let Everyone Advance with Dignity)

|

Yes/No | ||||

| Drop-Off Centers/Crisis Stabilization Units (CSUs)

a. Transport to place other than jail or ED b. Accept all referrals c. Medical clearance not required (or able to do medical clearance on site) d. Staffed 24/7/365 e. Follow-up provided |

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No e. Yes/No |

a.

b. c. d. e. |

a.

b. c. d. e. |

a.

b. c. d. e. |

a.

b. c. d. e. |

| Emergency Shelter

a. Options for families and individuals b. Low-barrier options for people actively using substances (“wet” shelters) c. Dedicated shelter beds for people in crisis d. Connections provided to permanent housing

|

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No

|

a.

b. c. d.

|

a.

b. c. d.

|

a.

b. c. d.

|

a.

b. c. d.

|

| Other Housing Options/Services

a. Transitional housing using Housing First approach and with connections to permanent housing b. Recovery housing as a treatment modality (not mandatory) c. Rapid Re-Housing d. Permanent Supportive Housing e. Housing navigation and referral services f. Wraparound supportive services and warm handoffs

|

a. Yes/No

b. Yes/No c. Yes/No d. Yes/No e. Yes/No f. Yes/No |

a.

b. c. d. e. f. |

a.

b. c. d. e. f. |

a.

b. c. d. e. f. |

a.

b. c. d. e. f. |

| Additional Programs/Policies [Insert rows as needed.]

|

Questions to Consider:

- How will you engage the community in the needs assessment process to ensure input from community members, including people with behavioral health needs, credible messengers, advocates, community volunteers, family members, and BIPOC community members?

- What is your plan for ensuring that all crisis responders coordinate around protocols for response, information sharing, common clients, and recommended referral services?

3: Conducting Emergency and Non-Emergency Call Triage

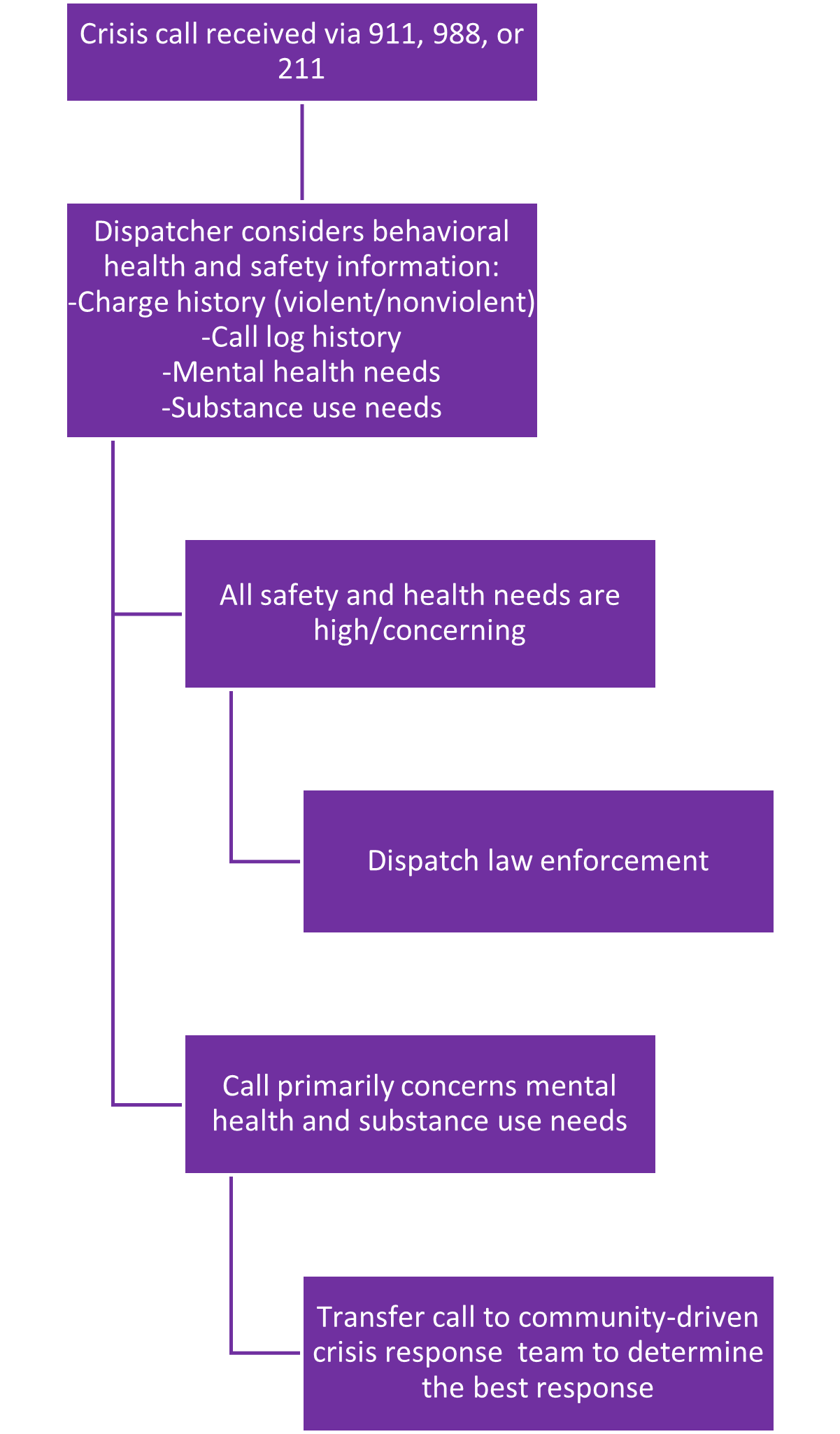

With the addition of the national 988 dialing code to existing call choices such as 911, 211, 311, and crisis lines, it is crucial to develop protocols for triaging calls to ensure that the best response is deployed. Communities whose crisis call line options and law enforcement agencies can adequately share information on prior client contact, safety concerns, medical needs, and behavioral health options are better positioned to leverage services.

Worksheet: Interagency Crisis Call Triage Decision Tree

Every jurisdiction has a different approach for triaging crisis calls. Factors that help determine a given community’s approach include the various crisis call lines in place, the information available to call dispatchers, and the types of responses available. The sample decision tree below may be of assistance in discussing and establishing collaboration among your planning team members to ensure that there is a clear protocol in place for routing calls to the community-driven crisis response. Use the blank decision tree below and adjust the layout as needed to indicate your community’s crisis call triage protocol.

Worksheet: Dispatch Model Comparison—What Works Best for Your Jurisdiction?

Use this chart to assess which dispatch entry point will work best for triaging calls to your community-driven crisis response.

| Type of Dispatch | Benefits | Challenges |

Is this the best option for your jurisdiction/system? Why or why not? |

| 911 Dispatcher | · Efficiency, as multiple call-takers and dispatchers can send calls to responders | · Requires increased training for call-takers and dispatchers on how to identify which calls should receive a crisis response

· Must have clear protocols for screening and diverting calls that are determined to be crisis- rather than crime-based |

· |

| Embedded Clinician | · Call-takers and dispatchers are likely already trained in identifying the signs of a behavioral health crisis and verbal de-escalation techniques

· If police officers are needed on the scene for higher-risk calls, clinicians can be conferenced in to de-escalate and gather information for the officers · By sharing the same physical space with clinicians (if possible), call-takers become more comfortable referring calls to the community-driven crisis response |

· Can be expensive to hire a clinician and add a new work station for them

· Clinician may take on multiple roles (such as screening for behavioral health issues; deciding whether to dispatch to community-driven crisis response; handle the call themselves; or reroute the call to police, fire, or EMS dispatch), potentially delaying dispatches

|

· |

| Outside Agency Line (e.g., 311, 211, 988, etc.) | · May handle both call-taking and dispatch

· Call-takers may have specialized training in behavioral health-related call response needs |

· Setting up an external hotline presents resource and cost constraints for jurisdictions

· May limit scope of community-driven crisis response calls to narrowly defined mental health calls based on the expertise of the agency |

· |

| Other Crisis Response Provider | · | · | · |

Questions to Consider:

- Is there an established process for communication among all emergency and non-emergency response lines? If so, which entity is responsible for monitoring and evaluating this process?

- Does your jurisdiction provide cross-training in mental health, trauma, substance use for all emergency and non-emergency response line call-takers and administrators?

- Have all agencies involved in emergency and non-emergency response agreed on clear protocols for when calls should be redirected to another agency?

- Have the agencies involved in emergency and non-emergency response identified a process for identifying the “familiar faces” in the community and whether they require special response or case management needs? If so, how is this information communicated across all agencies?

4: Community Responder Program (CRP) Staffing

Many communities are adding community responders, or a non-law enforcement response, to their options for addressing crisis calls. As best practices continue to emerge for these relatively new programs, there are different programming and staffing options to consider.

Worksheet: Recruitment and Staffing

Use this worksheet to track activities related to recruiting, staffing, and training staff for your community responder program.

Planning for Community Responder Program (CRP) Design

|

Activity |

In Progress | Completed | N/A |

Notes |

| 1. Engage in peer learning from various models and staffing options | ||||

| 2. Identify the program design | ||||

| 3. Determine the number of staff needed | ||||

| 4. Identify the level of training/education for the CRP | ||||

| 5. Identify the lead agency that will supervise the CRP | ||||

| 6. Identify roles and responsibilities for all partnering agencies | ||||

| 7. Establish memoranda of understanding and data-sharing protocols |

Preparing for Hiring and Program Implementation

| Activity | In Progress | Completed | N/A | Notes |

| 1. All parties agree upon job descriptions and related policies | ||||

| 2. Lead agency posts available positions | ||||

| 3. Delineate interview and selection process | ||||

| 4. Gather an interview panel that is representative of all agencies involved | ||||

| 5. Develop an onboarding process that includes training on roles/responsibilities for all agencies, including safety protocols | ||||

| 6. All agencies outline and agree upon staff logistics (e.g., uniforms, vans, cell phones, vehicles, radios, laptops, office space, etc.) |

Ongoing Program and Staff Support

| Activity | In Progress | Completed | N/A | Notes |

| 1. Conduct ongoing training on staff wellness, trauma, cross-training regarding the various roles/systems/agencies, safety, cultural humility, etc. | ||||

| 2. Supervisors conduct regular check-ins with CRP staff | ||||

| 3. CRP staff are able to debrief with supervisors or other supportive staff after crisis encounters as needed | ||||

| 4. CRP staff receive training on entering data with fidelity into relevant system/software |

Questions to Consider:

- Have the partnering agencies identified which call types will be responded to by the community responder program?

- Will this impact the staffing needs of the program?

- Will the responders be deployed alone or in two-person, three-person, or four-person teams? Or will there be a combination of team sizes depending on the call type?

- Will a government agency house this program or will it be implemented by a different entity or new agency?

- How will the job descriptions reflect the community’s needs?

- Have the partnering agencies determined the logistics required to secure uniforms, cell phones, vehicles, radios, laptops/tablets, and office space?

5: Use of Data to Inform Decision-Making

Applying local data is essential for informing planning and implementation; staffing capacity needs; programming decisions, such as hours of service and geographic placement of services; and the make-up of the responding team. Post-implementation tracking of the outcomes of each crisis response program or service informs the need for protocol changes, highlights service needs, and helps makes the case for sustaining the programs/services over time.

Worksheet: Data Inventory Checklist

Once the components of a community-driven crisis response system are operating, planning team members must routinely collect data regarding their daily functions and activities to evaluate performance and success. Collecting and evaluating this data illustrates what aspects of the programs/services are working, what elements need to be changed, and if goals are being met.

Although data collection details will vary from program to program, several metrics are routinely collected. Below is a list of these commonly tracked metrics to use as a starting point. For reference, note the following definitions:

- Call (for service) = the initial communication received by the crisis line

- Response = The responder/team was dispatched to the scene or the crisis was responded to by phone

- Encounter = Engagement with a client/patient

- Referral = The client/patient received information to access a service

Call and Response Data Metrics²

|

Data Metric

|

Currently tracked? | Where is this data located? | Who has access to this data? | Who enters this data? | Who can prepare this data for analysis and reporting? |

| # of total incoming calls for service | |||||

| # of incoming calls identified for community-driven crisis response program dispatch | |||||

| # of calls for service responded to | |||||

| # of unique individuals³ served | |||||

| Breakdown of unique individuals served by age, race, ethnicity, and gender | |||||

| # of repeat calls from unique individuals |

Outcome Metrics4

| Data Metric

|

Currently tracked? | Where is this data located? | Who has access to this data? | Who enters this data? |

Who can prepare this data for analysis and reporting? |

| # of unique individuals who received referrals | |||||

| Breakdown of unique individuals who received referrals by age, race, ethnicity, and gender | |||||

| # of unique individuals who declined referrals | |||||

| Breakdown of unique individuals who declined referrals by age, race, ethnicity, and gender | |||||

| # of unique individuals transported to a diversion drop-off center or CSU | |||||

| Breakdown of unique individuals transported to a diversion drop-off center or CSU by age, race, ethnicity, and gender | |||||

| # of times police back-up was required | |||||

| # of de-escalated calls not requiring police back-up | |||||

| # of unique individuals needing additional emergency services (i.e., having medical needs) | |||||

| Breakdown of unique individuals needing additional emergency services by age, race, ethnicity, and gender | |||||

| # of encounters diverted from emergency services | |||||

| # of encounters resulting in diversion from hospitals/emergency departments | |||||

| # of encounters resulting in diversion from jails | |||||

| # of encounters resolved at the scene | |||||

| # of encounters that received follow-up |

Existing programs frequently track not only how many crises/incidents they respond to, but also the type of crisis/incident (e.g., mental health, substance use, public disturbance, public indecency, homelessness, etc.). Further, many existing programs also independently track the types of services that are provided in the course of each response (mental health assessment, wellness check, resource provision, medical care provision, referrals, transportation, etc.).

Questions to Consider:

- Does your planning team intend to establish a subcommittee to capture and analyze aggregated and deidentified baseline data on behavioral health-related calls for service?

- If so, list subcommittee partners and staff with the necessary expertise and capacity to complete baseline data collection.

- Will this subcommittee create a data collection plan?

- Who will have access to the data and how you will ensure that Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA)/privacy laws are followed in any data sharing or reporting?

- If you have baseline data available, is it ready for analysis and reporting?

- How do the data metrics you will collect align with the goals of the crisis response programs/services? Community priorities? Advisory group priorities?

- Do the individual crisis response programs/services plan to conduct outcome and/or process evaluation(s)?

- Will you share any data that is accessible to the public (e.g., through data dashboards)? If so, how will you ensure that the data shared is transparent while adhering to privacy laws?

6: Safety Protocols and Wellness for All Individuals

Safety for everyone involved in a crisis call—including the person in crisis, responders, and other members of the public at the scene—must be the highest priority. Ensuring that all staff are trained on safety protocols, properly equipped, and supported with back-up as needed must be standard protocol. To support the continued well-being of both staff and community members after crisis calls occur, conduct post-call follow-up with the person who was in crisis and their family; hold post-call debriefs with staff; and include trauma care in staff protocols.

Worksheet

Use the chart below to document protocols that promote safety and well-being for all individuals on the scene.

|

Safety and Wellness Element |

Protocol Summary | Responsible Agency/Staff |

| Create protocols for flagging any safety concerns and engaging law enforcement prior to responding to a call for service | ||

| Provide ongoing supervision that supports staff during or immediately after they are dispatched to a crisis call5 | ||

| Establish clear protocols for accessing back-up or including law enforcement on the scene during a call response | ||

| Offer regular wellness checks for community-driven crisis response staff6 | ||

| Ensure adequate staffing ratios7 | ||

| Offer competitive benefits, compensation, and work schedules | ||

| Follow up with the person in crisis and their family after the call for service to ensure connections to services and supports |

[1] This can include practicing trauma-informed de-escalation techniques, supporting positive interactions among everyone involved, 24/7 consultations to an on-call supervisor, and equipping staff with rapid response communication devices.

[2] Checks can be done in a variety of ways (one-on-one sessions with a supervisor, licensed mental health clinician, or screening tools to assess burnout). Note that this role can be particularly stressful for people who are working as peers or who have their own mental health conditions or a lived experience with crisis systems, making wellness checks critically important for these staff.

[3] This will vary depending on the structure used. For example, many community responder teams dispatch 2-4 responders per call.

Questions to Consider:

- Has the planning team determined the call types or situations that would require calling for back-up (e.g., unforeseen medical situation, if someone becomes violent, etc.)?

- Who are the partners that you will need to work with to develop safety and wellness protocols for everyone involved in the call response (including the person in crisis)?

- Will staff be cross-trained on safety protocols?

- Will staff receive training/information about how to access staff wellness resources?

7: Financial Sustainability for Community-Driven Crisis Response Programs and Services

Sustainability planning should begin at the onset of the programs and services that comprise your community-driven crisis response system. If a program received a grant to support start-up costs, investigate options for future funding sources—including federal, state, and local sources, as well as philanthropic/private foundations. Leveraging the quantitative data collected to demonstrate successful outcomes (see Section 5), as well as qualitative data via stories from individuals benefitting from the services, will support your case for additional funding.

Worksheet: Identifying Existing Resources Chart

- List the specific funding sources used (or that you plan to use) to pay for the various components of each program/service. Include current and future (already awarded) funding sources. Use the Find a Federal Funding Opportunity database to explore and identify new federal funding opportunities.

- Complete the remaining columns for each of the funding sources that you listed.

- Note any restrictions on funding uses (e.g., funding can only be used for community-based mental health treatment, etc.).

- Identify the relative flexibility of each funding source to help you decide in what order to apply resources to the overall budget for each program/service.

[Name of Program/Service]

|

Funding Source |

Funding Type | Length of Funding | Funding End Date | Renewable Funding? | Funding Restrictions |

Funding Flexibility |

| ☐ One-Time

☐ Annual ☐ Multi-Year |

☐ Low

☐ Medium ☐ High |

|||||

| ☐ One-Time

☐ Annual ☐ Multi-Year |

☐ Low

☐ Medium ☐ High |

|||||

| ☐ One-Time

☐ Annual ☐ Multi-Year |

☐ Low

☐ Medium ☐ High |

[Name of Program/Service]

|

Funding Source |

Funding Type | Length of Funding | Funding End Date | Renewable Funding? | Funding Restrictions |

Funding Flexibility |

| ☐ One-Time

☐ Annual ☐ Multi-Year |

☐ Low

☐ Medium ☐ High |

|||||

| ☐ One-Time

☐ Annual ☐ Multi-Year |

☐ Low

☐ Medium ☐ High |

|||||

| ☐ One-Time

☐ Annual ☐ Multi-Year |

☐ Low

☐ Medium ☐ High |

[Name of Program/Service]

|

Funding Source |

Funding Type | Length of Funding | Funding End Date | Renewable Funding? | Funding Restrictions |

Funding Flexibility |

| ☐ One-Time

☐ Annual ☐ Multi-Year |

☐ Low

☐ Medium ☐ High |

|||||

| ☐ One-Time

☐ Annual ☐ Multi-Year |

☐ Low

☐ Medium ☐ High |

|||||

| ☐ One-Time

☐ Annual ☐ Multi-Year |

☐ Low

☐ Medium ☐ High |

[Add additional rows as needed.]

Questions to Consider:

- Have you considered which program components will require future funding planning?

- Have you considered funding from a variety of sources (e.g., federal grants; federal entitlements such as Supplemental Security Income [SSI] or Medicaid; Veterans Benefits; state, local, philanthropic, foundation funding, etc.)?

- Do your programs leverage resources (money, staff, or in-kind supports) from a larger or pre-existing effort? If not, consider if there are partners that might be interested in supplying resources to support this initiative or how you could work together to achieve a common goal.

- What data metrics are your funders interested in? Are you able to collect and report out on that data consistently?

Do you have plans to conduct program evaluations, including a survey of people served by each program, the results of which can be used to advocate for funding?

8: Legislation to Support Community-Driven Crisis Response Programs/Services

As you plan to enhance your community-driven crisis response system, you may identify barriers that require legislative changes or funding streams that could open up with legislative support. For these situations and others, it is important to cultivate relationships with key legislators and develop champions and a platform for your work.

Worksheet: Building Buy-In and Support for Legislation

The planning team should complete many of the activities in the worksheet below. Note that some of these items may be duplicative of the activities in Section 1 on stakeholder and community engagement.

|

Activity |

In Progress | Completed | N/A |

Notes |

| Assess the community’s level of support for behavioral health crisis response/improving social services | ||||

| Hold focus groups/listening sessions with community members | ||||

| Educate the community on the purpose and need for the community-driven crisis response system | ||||

| Include the community-driven crisis response system updates in the agenda for all county reports | ||||

| List the community-driven crisis response system champions | ||||

| Identify legislative/policy changes that can support the community-driven crisis response system operations/goals | ||||

| Keep champions informed of needs for legislative/policy changes | ||||

| Examine legislation from other cities, counties, or states for examples | ||||

| Examine results from other locations where relevant legislation has passed (e.g., improved outcomes, access to services, etc.) | ||||

| Prepare general talking points for champions/stakeholders | ||||

| Supply champions/stakeholders with data and supporting information about community-driven crisis response programs/services | ||||

| Update champions/stakeholders on community-driven crisis response data and anecdotal evidence/poignant stories about its impact | ||||

| Champions/stakeholders have talking points that are specifically geared toward addressing any potential concerns from the community/opposition |

Questions to Consider:

- What is the communications plan/community education plan for discussing the benefits and needs of community-driven crisis response programs/services with the community?

- How can you identify, engage, and uplift the voices of people with lived experience of behavioral health crisis in your advocacy for legislation that supports your community-driven crisis response programs/services?

- What is your plan for handling opposition to the legislation that supports community-driven crisis response programs/services (i.e., anticipating the political landscape in advance)? How can you address any potential concerns from the community?

Endnotes

1. “Familiar faces” refers to community members who frequently encounter criminal justice, behavioral health, and social service systems.

2. These metrics highlight whether services successfully meet the needs of the community, the ability of community-driven crisis response programs to respond to calls they receive, and how frequently individuals are using the program.

3. Count each person only once.

4. These metrics measure whether the program is meeting its stated goals. By analyzing whether individuals are accepting treatment or are being diverted from emergency services, program staff can determine which elements of the program work and which are lacking.

5. This can include practicing trauma-informed de-escalation techniques, supporting positive interactions among everyone involved, 24/7 consultations to an on-call supervisor, and equipping staff with rapid response communication devices.

6. Checks can be done in a variety of ways (one-on-one sessions with a supervisor, licensed mental health clinician, or screening tools to assess burnout). Note that this role can be particularly stressful for people who are working as peers or who have their own mental health conditions or a lived experience with crisis systems, making wellness checks critically important for these staff.

7. This will vary depending on the structure used. For example, many community responder teams dispatch 2-4 responders per call.

This project was supported by Grant No. 2019-MO-BX-K002 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Project Credits

Writing and Research: Felicia López-Wright, Risë Haneberg

Advising: Ashtan Grace Towles, Anne Larsen, Sarah Wurzburg

Editing: Katy Albis, Darby Baham, Amelia Vorpahl, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Aisha Jamil, CSG Justice Center

Cover Design: Stephanie Northern, CSG Justice Center

Web Development: Catherine Allary, CSG Justice Center

About the author

The sharp rise in school shootings over the past 25 years has led school officials across the U.S.…

Read MoreA three-digit crisis line, 988, launched two years ago to supplement—not necessarily replace—911. Calling 988 simplifies access to…

Read MoreIt would hardly be controversial to expect an ambulance to arrive if someone called 911 for a physical…

Read More Taking the HEAT Out of Campus Crises: A Proactive Approach to College Safety

Taking the HEAT Out of Campus Crises: A Proactive Approach to College Safety

The sharp rise in school shootings over the past 25 years has…

Read More From 911 to 988: Salt Lake City’s Innovative Dispatch Diversion Program Gives More Crisis Options

From 911 to 988: Salt Lake City’s Innovative Dispatch Diversion Program Gives More Crisis Options

A three-digit crisis line, 988, launched two years ago to supplement—not necessarily…

Read More Matching Care to Need: 5 Facts on How to Improve Behavioral Health Crisis Response

Matching Care to Need: 5 Facts on How to Improve Behavioral Health Crisis Response

It would hardly be controversial to expect an ambulance to arrive if…

Read More