Justice Reinvestment in Vermont: Improving Supervision to Reduce Recidivism

Justice Reinvestment in Vermont: Improving Supervision to Reduce Recidivism

This policy framework outlines policy options developed as part of a Justice Reinvestment Initiative effort in Vermont in 2019 in collaboration with Vermont’s Justice Reinvestment II Working Group. Many of the policies were reflected in legislation signed into law in 2020. The aim of these policies was to improve post-release supervision, achieve a more equitable criminal justice system, increase data collection and analysis, and, ultimately, reduce recidivism.

Overview

Despite decreases in Vermont’s corrections populations over the past decade, the state’s prisons were overcrowded prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, with the state paying to house 276 incarcerated people in out-of-state contract beds at the end of 2019.¹ From 2017 to 2019, nearly 80 percent of all prison admissions to Vermont’s overcapacity facilities were for supervision returns or revocations.² There was also an overrepresentation of Black people in the correctional system.³ In addition, the state faced challenges appropriately identifying the complex behavioral health needs of the prison and post-release supervision populations. With limited resources, Vermont struggled to support people who are at a high risk of failing on supervision with appropriate treatment, programs, and housing. Vermont also grappled with significant challenges related to the ongoing collection and analysis of criminal justice data to inform policy and decision-making. Many of the aforementioned challenges are ongoing.

In June 2019, Vermont leaders representing all three branches of government requested support from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) and The Pew Charitable Trusts (Pew) to use a Justice Reinvestment Initiative (JRI) approach to identify solutions to address these issues.4 As public-private partners in the federal JRI program, BJA and Pew approved Vermont state leaders’ request and asked The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center to provide intensive technical assistance. Governor Phil Scott signed an executive order establishing an 18-member bipartisan Justice Reinvestment II Working Group, chaired by Chief Justice Paul Reiber and composed of designees from the legislative, judicial, and executive branches.5 The Justice Reinvestment II Working Group partnered with CSG Justice Center staff to analyze data, address challenges in the state’s adult criminal justice system, and develop a set of proposed policies.

Many of these policies were reflected in House Bill (H) 760 and Senate Bill (S) 338, which were signed into law in March and July 2020 as Act 88 and Act 148, respectively. The legislation also continued the Justice Reinvestment II Working Group with the addition of a representative from the Vermont Parole Board to oversee the implementation of these policies. The state expects to reduce recidivism and avert $9.9 –12.4 million in corrections costs by 2025.

Vermont Justice Reinvestment II Working Group

The working group met five times between September 2019 and January 2020 to review analyses and discuss policy options. Members included representatives from the Depart-ment of Corrections (DOC), the Department of Health, the Department of Mental Health, the Department of State’s Attorneys and Sheriffs, the Office of the Defender General, the Office of the Vermont Attorney General, and victims’ rights and advocacy organizations.

Working Group Members

Chair

Paul L. Reiber, Chief Justice, Vermont Supreme Court

Members

John Campbell, Executive Director, Department of State’s Attorneys and Sheriffs

Xusana Davis, Executive Director, Racial Equity

Kelly Dougherty, Deputy Commissioner, Alcohol and Drug Abuse Programs, Department of Health

Alice Emmons, State Representative, Windsor-3-2 District

Patricia Gabel, then-Court Administrator, Vermont Supreme Court

Maxine Grad, State Representative, Washington-7 District

Christopher Herrick, Deputy Commissioner, Department of Public Safety

Jaye Johnson, Legal Counsel, Governor’s Office

James Duff Lyall, Executive Director, ACLU of Vermont

Alice Nitka, State Senator, Windsor District

David Scherr, then-Co-Chief of Community Justice Division, Attorney General’s Office

Dick Sears, State Senator, Bennington District

Kendal Smith, Director of Policy Development and Legislative Affairs, Governor’s Office

Sarah Squirrell, then-Commissioner, Department of Mental Health

Mike Touchette, then-Commissioner, Department of Corrections/James Baker, then-Interim Commissioner, Department of Corrections

Karen Tronsgard-Scott, Executive Director, Vermont Network Against Domestic and Sexual Violence

Matthew Valerio, Defender General

Data Collection

Extensive data were provided to the CSG Justice Center by the DOC, the Vermont judiciary, and the Vermont Department of Public Safety. In total, nearly half a million individual data records spanning 2014 to 2019 were analyzed across these databases, including supervision and prison populations and admissions; risk assessments; parole board decision-making; court case filing and sentencing; and statewide crime trends. Vermont has not conducted an analysis on this scale, in terms of breadth and depth, since it first engaged in the Justice Reinvestment Initiative in 2007. This data analysis was critical to the CSG Justice Center’s ability to help the Justice Reinvestment II Working Group understand the challenges within Vermont’s adult criminal justice system and develop policy recommendations. More than 200 in-person meetings and conference calls with judges; state’s attorneys; public defenders; field officers (probation, parole, and community corrections); law enforcement officials; behavioral health service providers; victims and their advocates; people in the criminal justice system, as well as their advocates; and others provided additional context and information for the analysis.

Key Challenges

Vermont’s post-release supervision system is highly intricate, and the state does not provide adequate resources to support people on community supervision who have complex needs. There are racial and geographic disparities in the state’s corrections population, and data analytic capacity challenges limit policymakers’ ability to understand the drivers behind these disparities as well as other criminal justice system challenges. Through its review of state data, the CSG Justice Center identified the following key challenges and related findings for the Vermont Justice Reinvestment II Working Group. All qualitative findings in this report are from CSG Justice Center staff’s assessment of Vermont’s criminal justice system from August to December 2019.

1. Large numbers of revocations and returns from supervision.

From FY2017 to FY2019, nearly 80 percent of all Vermont prison admissions were for supervision returns or revocations (77 percent for men and 85 percent for women).6 Of the prison admissions due to supervision returns or revocations, over half (53 percent) were people on furlough, 20 percent were people on probation, and just 5 percent were people on parole during the same period.7 Vermont’s community supervision system was complex with many legal statuses, particularly for furlough supervision, which is a correctional status under which the DOC may release a person from their sentenced period of incarceration for reintegration into the community. People on furlough are under DOC supervision; however, unlike people on probation or parole, they are still legally in DOC custody and could be returned to prison with fewer due process considerations, such as legal representation during violation hearings.

2. Insufficient identification of behavorial health needs and connection to treatment and services.

There were gaps in how people who have mental health and substance use needs in Vermont’s criminal justice system are identified and connected to appropriate treatments and services, including housing. While there were case planning policies in place to ensure that behavioral health information guides treatment and programming referrals, information sharing challenges existed between DOC’s private health care contractor, DOC facility reentry case workers, and supervision officers, as well as community-based providers. In addition, risk and need assessments and behavioral health screenings were rarely conducted prior to sentencing, resulting in supervision sentences and conditions being set without the information necessary to understand programming and treatment needs.

3. Lack of resources to support people on supervision with complex needs.

Funding for DOC and available resources for community-based programs were inadequate to serve the state’s high-risk, high- and complex-needs corrections populations. Level DOC funding in recent years had left the department unable to provide the behavioral health programs and services people need to succeed in the community. In addition, limited resources resulted in almost half of people on supervision assessed at a medium to high risk being unable to participate in risk-reduction programming. Space and budget challenges also limited DOC’s ability to provide sufficient gender-responsive programming to meet the needs of incarcerated women. Additionally, funding models undermined the sustainability of domestic violence accountability programs provided across the state and did not allow for a more risk-based approach to addressing domestic violence in the community.

4. Racial disparities.

Black people were overrepresented in Vermont’s corrections populations, particularly among incarcerated people.8 Data challenges, including inconsistent collection of race and ethnicity data, limited the state’s ability to fully analyze the drivers behind racial disparities or identify where changes in policy and sentencing structures may reduce these disparities.

5. Lack of consistent, ongoing data collection and analysis.

The Justice Reinvestment II Working Group analysis was a significant step toward improving the availability of data across systems in Vermont. However, it also highlighted additional challenges to ensuring ongoing data capacity to not only monitor Justice Reinvestment Initiative reforms but also to inform future policy and practice improvements.

Summary of Proposed Policy Options and Impacts

The policy options proposed by the working group and listed here were designed to achieve the following goals:

• Simplify post-release supervision to create clear release expectations for people on supervision, victims of crime, and other stakeholders.

• Improve the identification of and connections to existing treatment and services for people on supervision with behavioral health needs.

• Strengthen and expand the resources available to people with complex needs who are on community supervision to better address their needs and reduce their likelihood of recidivism.

• Achieve a more equitable criminal justice system across demographics, including race.

• Increase data collection and analysis capacity to support ongoing data-driven decision-making.

• Reduce recidivism by 5 to 20 percent to create savings of 102–131 prison beds by 2025.

Summary of Policy Options

1. Establish presumptive parole, initially for people convicted of non-listed offenses9 and later for a larger population that includes people convicted of some listed offenses.

2. Strengthen legislation enacted in 2019 that would allow people to earn time off their minimum incarceration sentence to incentivize good behavior.

3. Streamline the existing furlough system by consolidating and repealing several furlough legal statuses as well as creating a primary furlough status called Community Supervision Furlough.

4. Strengthen the effectiveness of incentive and graduated sanction violation responses for people on community supervision to safely reduce the number of people returned and revoked to prison from community supervision.

5. Identify opportunities to provide more risk and needs information at sentencing to better guide program and treatment planning during supervision.

6. Develop more robust identification of behavioral health challenges among people within the criminal justice system and strengthen connections to community-based treatment for people with mental illnesses, substance use disorders, and co-occurring disorders.

7. Direct the Sentencing Commission, the Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice and Juvenile Justice System Advisory Panel (RDAP), and key criminal justice stakeholders to identify data and resources needed to assess the relationship between demographic information and sentencing outcomes.

8. Strengthen and restructure domestic violence treatment programs to ensure a more sustainable funding model and provide more risk-informed programming options for people convicted of domestic violence offenses.

9. Expand DOC’s risk-reduction programming for all people on supervision who have medium to high criminogenic risk.

10. Increase gender-responsive and trauma-informed training and programming at the Chittenden Regional Correctional Facility, the state’s only female DOC facility, to address needs that may be contributing to recidivism.

11. Assess and quantify reentry housing needs for the DOC population and expand access to Housing First options.

Projected Impact

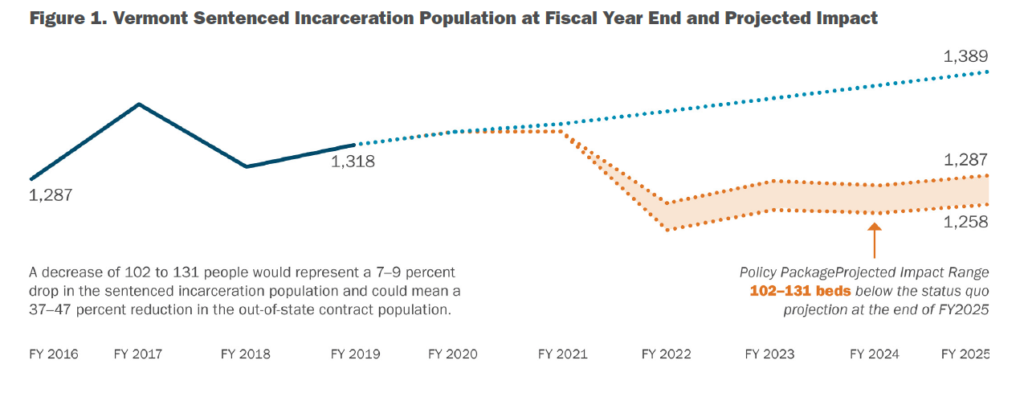

Prior to the onset of COVID-19, Vermont’s prisons were over capacity, resulting in people being housed in out-of-state prison facilities. From 2017 to 2019, Vermont’s sentenced incarceration population grew 1 percent.10 Had this growth continued, Vermont was projected to spend an additional $43 million by 2025 for out-of-state prison beds, assuming the contract rate were to remain the same.

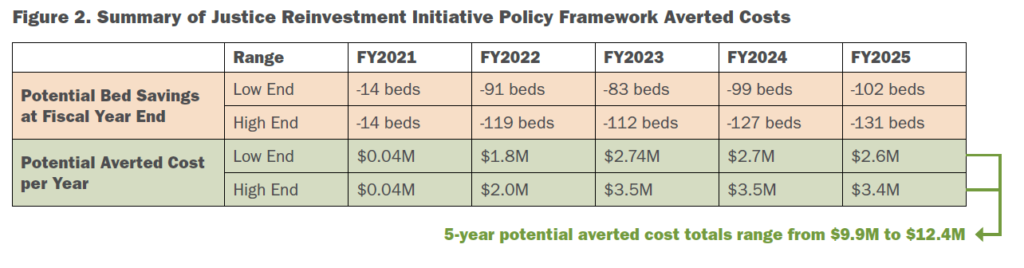

The proposed policy options were estimated to help Vermont potentially avert $9.9–12.4 million in costs by reducing its sentenced prison population by 102–131 people by the end of fiscal year (FY) 2025 (see Figures 1 and 2). The CSG Justice Center developed this five-year (FY2021–FY2025) impact projection using historical data and assumptions based on a combination of all policy options. However, impacts to the sentenced incarceration population are derived primarily from establishing presumptive parole, reducing revocations to prison, and strengthening Vermont’s earned good time law.11 Figure 2 provides an overview of potential bed savings and averted costs per year from FY2021 to FY2025.

It is important to note that these projections were based on 2017–2019 Vermont DOC admissions data and a population snapshot from June 30, 2019, and were created prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the modeling assumed a much larger sentenced population than currently exists due to population reductions related to COVID-19. Because of the ongoing nature of the pandemic, it is not yet possible to model the future impacts of COVID-19 on Vermont’s criminal justice system broadly or on Justice Reinvestment Initiative policy changes specifically. As a result, estimates of future bed savings and averted costs represent projected outcomes pre-pandemic and should be considered only within this limited context.

Up-front Investments and Reinvestments

To help Vermont meet the goals of Justice Reinvestment II, the proposed policy options required initial as well as continued investments. Legislative leadership included an up-front investment of $2 million in S. 338, including $400,000 for domestic violence intervention programming, $600,000 for evidence-based community programming, and $1 million for evidence-based transitional housing. Unfortunately, this appropriation was removed due to budget concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Vermont’s FY2021 budget did designate any out-of-state bed savings for investment in expanding community-based services to support Justice Reinvestment Initiative outcomes. Out-of-state bed savings for FY2021 were estimated to be $360,000.

The Governor’s Recommended Budget for FY2022 re-proposed several initial funding options, including $200,000 to maintain investments in domestic violence intervention programming, $400,000 to target gaps in mental health and substance use services, and $300,000 to strengthen transitional housing options and efficacy. These allocations were included in the FY2022 budget.

Figure 3. Proposed FY2021 and FY2022 Up-frontInvestments to Support Justice Reinvestment Initiative Policy Options

| FY2021 | FY2022 | |

| Expand risk-reduction strategies | $600K | – |

| Strengthen and sustain domestic violence treatment programs | $400K | $200K |

| Support reentry housing | $1M | $300K |

| Target gaps in mental health and substance use services | – | $400K |

| Total Investment | $2M | $900K |

Proposed Policy Option Details

1. POLICY OPTION

Establish presumptive parole, initially for people convicted of non-listed offenses and later for a larger population that includes people convicted of some listed offenses.

Background

Parole was overwhelmingly granted to people who have already navigated some of the highest-risk months while supervised on furlough after having served their minimum incarceration sentences. Between FY2017 and FY2019, 90 percent of people who were granted parole had already been in the community on furlough, with only an estimated 10 percent of people paroled without first being furloughed.12

There were more technical returns and revocations for people on furlough than people on parole. Between January and October 2019, 77 percent of returns to prison for people on furlough were for technical violations.13 During the same period, 49 percent of revocations for people on parole were for technical reasons.14 Furlough is a status that is considered an extension of incarceration; therefore, the conditions of release are often more cumbersome than those of parole. In addition, community corrections officers supervising people on furlough were not consistently trained in evidence-based correctional practices.15

There were fewer people convicted of unlisted offenses incarcerated in DOC facilities than people convicted of listed offenses. In 2019, 77 percent of DOC’s sentenced incarcerated population included people convicted of a listed offense.16

Policy Option Details (Enacted as Act 148)

A. Establish presumptive parole. People convicted of unlisted offenses that meet established criteria, including good behavior, became eligible for parole effective January 1, 2021. Excluding the “Big 12,”17 people convicted of listed offenses will be eligible effective January 1, 2023. The long-term inclusion of people convicted of listed offenses is critical for presumptive parole to have the broadest potential impact on the state’s incarcerated population.

B. Allow the parole board to conduct an administrative review of all presumptive parole cases prior to release. Establish that the parole board may deny presumptive release and set a hearing only if there is a victim of record that should be given the opportunity to participate.

2. POLICY OPTION

Strengthen recently enacted legislation that would allow people to earn time off their minimum incarceration sentence to incentivize good behavior.

Background

In the past, Vermont offered people as much as 10 days off their minimum sentence for 30 days without a disciplinary rule violation (DRV). However, a statute enacted in 2019 allowed a person serving an incarceration sentence to earn only 5 days off their minimum for 30 days without a DRV.18

State statute required earning good time to be dependent on program completion. But this made good time difficult to calculate and track for DOC staff and may have led to inaccuracies in these calculations.19

Policy Option Details (Enacted as Act 148)

Allow people to earn 7 days off their minimum sentence for every 30 days they are incarcerated without a major DRV (e.g., violence or serious threats directed at staff) and remove the requirement to participate in DOC-recommended programming to earn time off. Additional earned time may further incentivize good behavior while achieving more savings that can be reinvested in supervision programming and treatment. This policy will also be applied to the current incarcerated population.

3. POLICY OPTION

Streamline the existing furlough supervision system by consolidating and repealing several furlough legal statuses as well as creating a primary furlough status called Community Supervision Furlough.

Background

Vermont’s furlough system was undermined by its complexity. Prior to 2021, there were 17 different furlough legal statuses and each status had different administrative requirements. The complexities of this system resulted in supervision staff focusing a large amount of time on navigating the varied requirements and reports for different statuses. It could also lead to confusion for victims of crime about when a person may be released from or returned to prison.20

Furlough supervision is an extension of incarceration; therefore, people on furlough did not have legal representation during revocation hearings, unlike people on parole and probation.21

Policy Option Details (Enacted as Act 148)

A. Streamline the furlough system by reducing 17 different furlough legal statuses to 10 and creating a new primary furlough status called Community Supervision Furlough. Community Supervision Furlough repurposes a current furlough status (Conditional Reentry) to be the primary release mechanism for people who have reached their minimum sentence and are not eligible for presumptive parole, at the discretion of DOC. Consolidating furlough statuses will create clearer release expectations among people who are sentenced, victims, and DOC facility and community supervision staff.

B. Create a review process for furlough returns or revocations with expanded due process. The furlough violation hearing process requires any recommendation for a furlough return of 90 days or longer to trigger a review by DOC Central Office, as well as notification to the Defender General Office.

4. POLICY OPTION

Strengthen the effectiveness of incentive and graduated sanction violation responses for people on community supervision to safely reduce the number of people returned and revoked to prison from community supervision.

Background

Nearly half of Vermont’s sentenced prison population in 2019 consisted of people who were returned from community supervision, primarily furlough. At the end of 2019, 27 percent of the DOC population were admitted for a furlough violation, 16 percent for a probation violation, and 3 percent for a parole violation.22

The average length of stay in prison for people who were returned or revoked due to supervision violations is short, but still impactful. Between January and October 2019, the average length of stay was 16 days for people on furlough, 34 days for people on parole, and 48 days for people on probation.23

The vast majority of furlough returns to incarceration were due to technical violations rather than new criminal offenses. Between January and October 2019, 77 percent of furlough returns were for technical violations.24 During the same period, 49 percent of parole and probation revocations were for technical violations.25

The number of furlough returns placed enormous strain on individuals as well as the corrections system. Between 2016 and 2019, CSG Justice Center analysis estimated that 2,929 individuals had furlough returns for a total of over 5,800 furlough return events. The average person had 2 furlough returns within these 4 years alone; 228 people (8 percent) had 5 or more furlough returns over the course of their time with DOC. The median length of time spent on furlough before returning to sentenced incarceration was 4 months.26

DOC did not have a formal incentives grid or structure to guide how officers use incentives to promote behavior change. DOC had a formal structure to guide officers on using negative reinforcements when responding to violations of supervision conditions but did not have a formal grid or structure for using positive reinforcements. Research shows that positive reinforcements and negative reinforcements should be used at a 4:1 ratio to successfully change behavior.27

Officers did not appear to consistently enter information about intermediate sanctions into the DOC case management system, which means DOC leadership could not monitor this policy. Field staff did not consistently receive coaching, and quality assurance mechanisms were not in place to ensure effective use of the system. Supervision officers reported that entering and retrieving information into the case management system can be cumbersome. This affected their ability to input or access necessary information and decreased the time they had to work with clients.28

There was a lack of consistency in how officers responded to non-compliance. There also appeared to be a strong reliance on incarceration responses for technical violations for people who are supervised on furlough, with graduated sanctions and furlough revocations.29

Policy Option Details (Enacted as Act 88)

Require DOC to report to the legislature on ways to strengthen existing graduated sanctions and incentives policies to ensure they reflect best practices, including recommendations and initial cost estimates regarding the following:

• Formalizing the use of incentives and sanctions at a 4:1 ratio of positive reinforcements to negative reinforcements and requiring incentives and sanctions to be entered and tracked in the community supervision case management system

• Analyzing how supervision staff currently understand, implement, and input sanction data into the DOC case management system and where practices might differ across the state. Where necessary, provide additional staff training on the use and tracking of graduated sanctions.

5. POLICY OPTION

Identify opportunities to provide more risk and needs information at sentencing to better guide program and treatment planning during supervision.

Background

Risk and needs assessments were rarely conducted for people before sentencing, and pre-sentence investigation reports were infrequently ordered to inform sentencing or supervision conditions. This resulted in supervision sentences and conditions that were set without objective information about which programs and supervision stipulations would be best suited to help a person succeed on community supervision.30

Officers were less able to modify probation supervision requirements compared to furlough or parole requirements because supervision conditions were set by the court. This included probation requirements that could be modified based on the results of a risk and needs assessment, like programming and treatment.31

Policy Option Details (Enacted as Act 148)

Direct the Justice Reinvestment II Working Group to identify ways to increase information available before sentencing about a person’s criminogenic risk and programming needs to inform conditions of supervision. Require the working group to make recommendations to the legislature by January 2021.

6. POLICY OPTION

Develop more robust identification of behavioral health challenges among people in the criminal justice system and strengthen connections to community-based treatment for people with mental illnesses, substance addictions, and co-occurring disorders.

Background

There were critical gaps in how people incarcerated within DOC facilities with behavioral health needs were identified and connected to resources. Behavioral health needs of people in DOC facilities are initially identified through a screening conducted by DOC’s private health care contractor, but there were information sharing inconsistencies between the contractor and DOC facility reentry case workers. If a person was identified with behavioral health needs, this information might not have been shared to inform the person’s case plan.32

There were also critical gaps in how people on supervision with behavioral health needs were identified and connected to resources. To identify the behavioral health needs of people on probation, DOC used the Supervision Level Assessment (SLA), which does not have any mental health screening questions. DOC also used the behavioral health domain on the Ohio Risk Assessment System (ORAS, a criminogenic risk and needs tool), instead of a behavioral health screen, to identify the behavioral health needs of people on furlough, parole, and split probation,33 as well as people on probation who score high on the SLA. However, the SLA and the ORAS behavioral health domain are not equivalent to a full behavioral health screening tool.34

Despite case planning policies aimed at ensuring that behavioral health information guides treatment and programming referrals, information sharing challenges prevented this information from being shared in a way that would best support effective reentry planning. These information sharing challenges existed between DOC’s private health care contractor, DOC facility reentry case workers, and supervision officers, as well as community-based providers.35

Policy Option Details (Enacted as Act 148)

A. Require the Agency of Human Services (AHS) to report the following information to the Justice Reinvestment II Working Group by December 2020:

• The nature and scope of available screening and assessment of mental health and substance use needs among incarcerated populations and how those results are connected to case plans developed for sentenced individuals while they are incarcerated and prior to their release onto community supervision, as well as people sentenced directly to probation

• Existing behavioral health collaborative care coordination and case management protocols for supporting people in DOC custody or on supervision who have mental health and substance use needs

• Challenges to information sharing between AHS agencies that engage people on supervision, as well as community providers and DOC staff

B. Require the Justice Reinvestment II Working Group to make recommendations to the legislature by January 2021 on ways to minimize gaps in screening and assessment and ensure that case plans reflect criminogenic, mental health, and substance use needs.

7. POLICY OPTION

Direct the Sentencing Commission, the Racial Disparities in the Criminal Justice and Juvenile Justice System Advisory Panel (RDAP), and key criminal justice stakeholders to better analyze and reduce racial disparities in the criminal justice system.

Background

Black people were the most overrepresented among supervised and incarcerated populations, with the highest overrepresentation in sentenced and detained populations. In 2019, Black people made up 1.4 percent of Vermont’s total population, but that year, Black men represented 10 percent of the male incarcerated population and Black women represented 6 percent of the female incarcerated population. In 2019, White people accounted for 92.6 percent of the state’s total population. In the same year, White men represented 84 percent of the male incarcerated population, and White women represented 92 percent of the female incarcerated population.36

In December 2019, the RDAP made recommendations to better understand and reduce racial disparities in the criminal and juvenile justice systems. Recommendations included providing adequate staffing and resources to collect and centralize data from police agencies across the state, as well as increasing data collection at high impact and high discretion points in the criminal justice system, such as charging, pretrial, and disposition.37

Policy Option Details (Enacted as Act 148)

A. Direct RDAP and other key stakeholders to identify available data that are relevant to understanding the relationship between demographic factors and sentencing outcomes, as well as determine where data gaps may exist. Require this group to also perform an initial analysis of racial disparities in sentencing patterns and make recommendations to the legislature for data and policy improvements by December 2020.

B. Require the Vermont Sentencing Commission to review RDAP’s findings and consider changes to the state’s sentencing structures that would reduce racial disparities. This includes exploring issuing nonbinding sentencing guidance. Require the Sentencing Commission to report policy recommendations to the legislature by February 2021.

8. POLICY OPTION

Strengthen and restructure domestic violence treatment programs to ensure a more sustainable funding model and provide more risk-informed programming options for people convicted of domestic violence offenses.

Background

Domestic violence-related felony sentencing has increased significantly in recent years, indicating the likelihood that more people need domestic violence programming and treatment as they move through the system and on to community supervision. Between 2015 and 2019, felony convictions for domestic violence offenses increased 23 percent, from 126 to 155 cases.38

Domestic violence community programming options had a limited ability to treat people of differing risk. The community programming available for people convicted of domestic violence was a “one-size-fits-all” approach that did not target people based on their risk and needs, undermining the efficacy of the programming for different people.39

Vermont’s domestic violence community programming was weakened by the funding model and lack of state investment and support. Funding for these domestic violence programs came entirely from participant fees, which can be prohibitively expensive for people and undermine their ability to complete or benefit from these programs. At the same time, funding inadequately supported many of these programs, which often did not have sufficient resources to provide their staff with the training required to meet statewide standards. Finally, Vermont no longer had a statewide domestic violence program coordinator, a position that formerly ensured consistency in access, quality, and compliance across all counties while also providing critical support to programs across the state.40

Policy Option Details (Initially Proposed in S. 338)

Legislative leadership initially included a $400,000 appropriation in S. 338 for risk-based domestic violence intervention programming and statewide coordination of those efforts through the Vermont Council on Domestic Violence. While this appropriation was removed due to budget uncertainties related to the COVID-19 pandemic, Vermont’s FY2021 budget did designate any out-of-state bed savings for investment in expanding community-based services to support Justice Reinvestment Initiative outcomes, including domestic violence intervention programming. Out-of-state bed savings for FY2021 were estimated to be $360,000.

Vermont also applied for and received an additional Justice Reinvestment Initiative award from BJA in November 2020 to fund a statewide coordinator and explore additional recommendations for addressing Vermont’s challenges related to domestic violence.

9. POLICY OPTION

Expand DOC’s risk-reduction programming for all people on supervision who have medium to high criminogenic risk.

Background

Existing DOC resources did not adequately support the full implementation of evidence-based practices and provision of risk-reduction programming (RRP) to all higher-risk people on supervision. With limited funding and resources, DOC prioritized RRP for people who are sentenced for listed offenses who score as medium to high risk on the ORAS.41

Among people on supervision, almost half of the medium-high risk population does not receive RRP. In 2019, 48 percent of the total medium- to high-risk population were ineligible for RRP in the community.42

Many people who are medium to high risk were not receiving RRP because they were not convicted of a listed offense. Vermont’s primary focus on people who are at a high risk for recidivism and are convicted of listed offenses resulted in large numbers of medium- to high-risk people who did not receive RRP even during the high-risk period just after release.43

Policy Option Details (Initially Proposed in S. 338)

Legislative leadership initially included a $500,000 appropriation in S. 338 to provide additional and necessary staffing resources to expand RRP for all eligible people under community supervision who have medium to high criminogenic risk. It would also have provided essential quality assurance measures and training for program contractors and staff who administer these services in the community. This allocation was removed during the 2020 legislative session to allow for more extensive analysis of DOC’s current resources and capability to offer these expanded services without additional funding from the legislature.

10. POLICY OPTION

Increase gender-responsive and trauma-informed training and programming at the Chittenden Regional Correctional Facility (CRCF), the state’s only female DOC facility, to address needs that may be contributing to recidivism.

Background

Both DOC staff and CRCF providers described the significance of budget and contract cuts on their ability to provide the full scope of programs they feel would benefit women inside CRCF. While CRCF providers submitted routine reports about services, there was limited to no direct service observation and case file review, which, if it occurred, could improve program fidelity.44

The CRCF building, which was originally designed as a holding facility for men, did not have adequate programming space. Programs were in high demand, particularly those that focus on substance use and addiction, and CRCF space limitations and staffing could result in wait lists for programming.45

Policy Option Details (Initially Proposed in S. 338)

Legislative leadership initially included a $100,000 appropriation in S. 338 to expand gender-responsive programming at CRCF. This appropriation was removed due to budget uncertainties related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

11. POLICY OPTION

Assess and quantify reentry housing needs for the DOC population and expand access to Housing First options.

Background

A lack of appropriate housing contributed to the high rate of people on supervision who fail and return to DOC’s overcrowded prison facilities. Between January and October 2019, for people who were returned for a furlough technical violation, over 40 percent of these violations cited loss of housing as a reason.46 During this same period, many people lost housing due to relapse.47

Some people leaving DOC did not succeed in congregate, sober-living settings and needed other housing options. The housing available to the corrections population largely consisted of beds and apartments in congregate, single-site locations, as opposed to scattered site apartments. Many of these were sober or recovery homes where there are no-tolerance policies regarding relapse, and some do not allow people on medication-assisted treatment (MAT) to be residents, even though MAT is an evidence-based approach to opioid use disorder.48

Research shows that a Housing First, permanent supportive housing model49 is an important option for people with complex needs. The Housing First model does not have preconditions, such as sobriety or mandatory program compliance, and offers voluntary services to maximize housing stability, such as substance use or mental health treatment. Studies on this housing approach, including the Frequent User Systems Engagement (FUSE) model, show positive outcomes for people with complex needs who frequently cycle through the corrections, housing, and health care systems.50

Vermont DOC had a transitional housing budget dedicated to supporting reentry for the sentenced population and established grants with an array of housing providers across the state, including sober and supportive housing. However, under DOC’s transitional housing program, approximately 20 percent of beds at any given time went unused. Some DOC clients were denied entry because of past violations of program agreements, resulting in vacant beds.51

There were opportunities to better quantify the housing needs of people who are incarcerated and coordinate across AHS departments to support this population. Housing needs were identified for people in the sentenced population during reentry case planning; however, there was no consistent screening provided to the sentenced population to determine the full scope of their housing needs, and there was no assessment for people in the detained population. Also, although DOC, the Department of Mental Health, and the Department of Health’s Division of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Programs have shared clients with behavioral health and housing needs, each of these agencies contracted separately with housing providers, which could lead to an uncoordinated response for the same person.52

Policy Option Details (Enacted as Act 88)

A. Direct DOC to submit a report to the legislature with recommendations, including initial cost estimates, related to the following:

• Developing and implementing a homeless screening tool and tracking reports of homelessness among corrections populations within DOC’s case management system

• Identifying and quantifying people who are high utilizers of corrections, homeless, and behavioral health services to inform statewide permanent supportive housing planning

• Establishing data match partnerships with appropriate AHS departments to match DOC, Homeless Management Information System, and Medicaid information

• Establishing a collaborative approach for AHS departments to contract with housing providers for the purpose of coordinating responses for shared clients and better leveraging local and federal housing vouchers

• Leveraging Medicaid or other funding to allow DOC clients to stay in supportive housing after they are no longer under DOC supervision

• Reducing barriers to recovery housing by establishing evidence-based norms and expectations for contracts and certifications for sober and recovery housing providers

• Redefining housing requirements for incarcerated people to receive approval for furlough release

B. Legislative leadership initially included a $1 million appropriation in S. 338 to strengthen housing models that are currently working well for DOC’s clients with complex needs and diversify access to DOC transitional housing across geographic regions. This appropriation was removed due to budget uncertainties related to the COVID-19 pandemic. This funding would have done the following:

• Increased funding for existing housing providers that are partnering well with DOC and their clients to strengthen services

• Expanded bed allotments with housing providers that are yielding positive outcomes

• Supported a request for proposal for a Housing First supportive housing program in communities where DOC either currently heavily relies on congregate housing and/or does not have housing

Endnotes

1. Analysis of FY2019 DOC data conducted by The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center, December 2019.

2. Analysis of FY2017–FY2019 DOC data conducted by CSG Justice Center, December 2019. Estimated as the average annual volume and proportion of admissions from FY2017 to FY2019.

3. Analysis of FY2019 DOC data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019.

4. Vermont leadership included Governor Phil Scott, Senate President Pro Tempore Tim Ashe, Speaker of the House Mitzi Johnson, Vermont Supreme Court Chief Justice Paul Reiber, Agency of Human Services Secretary Al Gobeille, Attorney General Thomas J. Donovan, and then-Department of Corrections Commissioner Mike Touchette.

5. Vermont first used a data-driven Justice Reinvestment Initiative approach in 2007, which resulted in a 16 percent drop in the incarcerated population.

6. Analysis of FY2017–FY2019 DOC data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019. Estimated as the average annual volume and proportion of admissions from FY2017 to FY2019.

7. Ibid.

8. Analysis of FY2019 DOC data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019.

9. Listed offenses are a set of the most serious crimes in Vermont as defined in 13 V.S.A. § 5301, including sexual assault, murder, and kidnapping. Non-listed offenses are less serious crimes, including drug possession, burglary, and larceny.

10. Analysis of FY2017–FY2019 DOC data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019.

11. The impact model includes a range of potential impacts based on the percent reduction in revocations from supervision that Vermont can achieve (5–20 percent reduction). Potential averted costs are based on the reduced incarceration population per year and calculated at the current out-of-state contract cost per person per day of $73.

12. Analysis of FY2017–FY2019 release data from the Vermont Parole Board conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019.

13. Analysis of DOC data on returns to incarceration conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019.

14. Analysis of DOC and Parole Board data on revocations conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019.

15. CSG Justice Center assessment based on community supervision observations, August–December 2019.

16. Analysis of FY2019 DOC population data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019.

17. Youthful Offender “Big 12” offenses are defined in V.S.A. § 5204(a) and are arson causing death, assault and robbery with a dangerous weapon, assault and robbery causing bodily injury, aggravated assault, murder, manslaughter, kidnapping, unlawful restraint, maiming, sexual assault, aggravated sexual assault, and burglary into an occupied dwelling.

18. CSG Justice Center assessment based on legal analysis, August–December 2019.

19. CSG Justice Center assessment based on legal analysis and review of past good time policies, August–December 2019.

20. CSG Justice Center assessment based on legal analysis and community supervision observations, August–December 2019.

21. CSG Justice Center assessment based on legal analysis, October 2019.

22. Analysis of FY2019 DOC data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019. Because admission and release categories must be derived using DOC data, these analyses should be considered strong estimates.

23. Analysis of DOC data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019. Because admission and release categories must be derived using DOC data, these analyses should be considered strong estimates.

24. Ibid.

25. Analysis of DOC and Parole Board data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019. Because admission and release categories must be derived using DOC data, these analyses should be considered strong estimates.

26. Analysis of DOC data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019. Because admission and release categories must be derived using DOC data, these analyses should be considered strong estimates.

27. CSG Justice Center assessment based on review of DOC supervision policies.

28. CSG Justice Center assessment based on community supervision observations, October–December 2019.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid.

31. CSG Justice Center assessment based on legal review and community supervision observations, August–December 2019.

32. CSG Justice Center assessment of DOC behavioral health interventions based on policy review and facility and community supervision observations, August–December 2019.

33. A person serving a split probation sentence may be moved to administrative probation at the discretion of DOC upon successfully completing half of their probation term.

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid.

36. Analysis of 2019 data from DOC and U.S. Census Bureau, Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin, April 1, 2010, to July 1, 2019, conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019.

37. Vermont Racial Disparities in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice System Advisory Panel, Report to the General Assembly (Montpelier: Racial Disparities in the Criminal and Juvenile Justice System Advisory Panel, 2019).

38. Analysis of disposition data from the Vermont Judiciary conducted by the CSG Justice Center, November 2019.

39. CSG Justice Center assessment of community-based domestic violence programming based on review of current practices, meetings with DOC, The Network Against Domestic and Sexual Violence, and other stakeholders, as well as focus groups with people in the criminal justice system, August–December 2019.

40. Ibid.

41. CSG Justice Center assessment based on review of existing RRP programming availability.

42. Analysis of DOC risk assessment data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019.

43. CSG Justice Center assessment based on review of existing RRP programming availability.

44. CSG Justice Center assessment based on review of existing gender-responsive programming, including observing programming at the Chittenden Regional Correctional Facility, November and December 2019.

45. CSG Justice Center assessment based on review of existing gender-responsive programming, including observing programming at the Chittenden Regional Correctional Facility, November and December 2019.

46. Analysis of Jan–Oct 2019 DOC furlough returns data conducted by the CSG Justice Center, December 2019.

47. CSG Justice Center assessment of reentry housing practices based on DOC facility and community supervision observations, as well as focus groups with people in the criminal justice system, October–December 2019.

48. For more information on MAT and Vermont’s Hub and Spoke model to expand access to MAT, see https://blueprintforhealth.vermont.gov/ about-blueprint/hub-and-spoke.

49. For more information on a Housing First, supportive housing model, see https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/Housing-First-Permanent- Supportive-Housing-Brief.pdf.

50. FUSE is a data-driven model that identifies the most frequent users of jails, shelters, emergency rooms, and other costly crisis services and uses supportive housing to help communities break the cycle of homelessness and crisis among these people with complex medical and behavioral health challenges. For more information on FUSE outcomes, see https://www.csh.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/FUSE-Eval-Report-Final_Linked.pdf.

51. CSG Justice Center assessment based on review of existing DOC Transitional Housing policies and practices and meetings with DOC leadership, August–December 2019.

52. Ibid.

This project was supported by Grant No. 2019- ZB-BX-K002 awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the SMART Office. Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center is a national nonprofit organization that serves policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels from all branches of government. The CSG Justice Center’s work in justice reinvestment is done in partnership with The Pew Charitable Trusts and the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance.

The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center is a national nonprofit organization that serves policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels from all branches of government. The CSG Justice Center’s work in justice reinvestment is done in partnership with The Pew Charitable Trusts and the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance.

These efforts have provided data-driven analyses and policy options to policymakers in 26 states. For additional information about Justice Reinvestment, please visit csgjusticecenter.org/jr/.

Research and analysis described in this report has been funded in part by The Pew Charitable Trusts public safety performance project. Launched in 2006 as a project of the Pew Center on the States, the public safety performance project seeks to help states advance fiscally sound, data-driven policies and practices in sentencing and corrections that protect public safety, hold people accountable, and control corrections costs. To learn more about the project, please visit pewtrusts.org/publicsafety.

Project Credits:

Writing: Cassondra Warney, Ellen Whelan-Wuest, Madeleine Dardeau, CSG Justice Center

Research: Ed Weckerly, CSG Justice Center

Advising: Sara Friedman, Elizabeth Lyon, Marshall Clement, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Leslie Griffin, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Brenna Callahan, CSG Justice Center

Project contacts:

Ellen Whelan-Wuest, Program Director, ewhelan-wuest@csg.org or

Madeleine Dardeau, Senior Policy Analyst, mdardeau@csg.org

About the authors

Arkansas policymakers have long expressed concerns about the state’s high recidivism rate. Over the past 10 years, an…

Read MoreIn April 2025, Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed a package of bipartisan criminal justice legislation into law,…

Read More Explainer: Key Findings and Options from Arkansas’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative

Explainer: Key Findings and Options from Arkansas’s Justice Reinvestment Initiative

Arkansas policymakers have long expressed concerns about the state’s high recidivism rate.…

Read More Explainer: How a New Law in Arkansas Tackles Crime, Recidivism, and Community Supervision Challenges

Explainer: How a New Law in Arkansas Tackles Crime, Recidivism, and Community Supervision Challenges

In April 2025, Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders signed a package of…

Read More