Trauma-Informed Approaches Across the Sequential Intercept Model

People in the criminal justice system experience alarming rates of trauma prior to and as a result of their involvement in the system. Yet criminal justice professionals have often struggled to recognize and respond to trauma among this population. This brief explores how criminal justice professionals can take a trauma-informed approach to their work at each point of contact in the justice system. By employing this approach, they can help to reduce recidivism and incidents of violence while also improving service engagement and recovery. Photo credit: Photo by Alex Green.

Trauma-Informed Approaches Across the Sequential Intercept Model

People in the criminal justice system experience alarming rates of trauma prior to and as a result of their involvement in the system.1 The prevalence rates of trauma among incarcerated women, for example, have been shown to be as high as 98 percent.2 Rates of trauma exposure among incarcerated men are between 62.4 and 87 percent.3 And both men and women report experiencing frequent physical or sexual victimization while incarcerated, which can traumatize or retraumatize a population that already experiences a higher rate of childhood victimization.4

Additionally, the over-representation of Black men in the criminal justice system5—a system which in itself can be traumatic for the individual, their family, and the community— has been a major contributing factor to the disproportionately high rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in the Black community.6

Despite this pervasiveness, criminal justice professionals have often struggled to recognize and respond to trauma among this population. They have also been reluctant at times to acknowledge the vicarious and direct trauma that staff can experience while working in the criminal justice system. However, with increased resources, support, and training, criminal justice professionals can begin to adequately identify and address trauma histories. To better support people who are impacted by trauma, these professionals must work with their behavioral health counterparts to better understand how trauma influences behavior. Then, they can take steps to minimize the long-term effects of exposure to traumatic events by implementing trauma-informed policies and practices.

This brief explores how criminal justice professionals can take a trauma-informed approach to their work at each point of contact in the justice system. By employing this approach, they can help to reduce recidivism and incidents of violence while also improving service engagement and recovery.7

Understanding Trauma’s Impact

While trauma is widespread among people in the criminal justice system, it is also experienced in many different ways. Because of this, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) established a broad definition for what trauma can look like for various people. According to SAMHSA, “individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.”8

The “three E’s” included in the SAMHSA definition distinguish trauma from other crises or negative life events because of the lasting effects the event(s) can have on a person. For example, trauma exposure has been associated with an increased risk for behavioral and physical health conditions and reduced engagement with health care services among people who are incarcerated and the general population.9 Research also shows that childhood stress and trauma can impair the development of executive functioning, which has been found to increase rates of physical aggression.10 Many of these long-term effects can lead to behaviors that result in arrest or a continuous cycle between the criminal justice and health systems. Examples of traumatic events can include interpersonal violence, such as intimate partner violence, child abuse, witnessing a shooting, or loss of a loved one. Food scarcity, discrimination, racially biased encounters with police officers, risk of homelessness, multiple military deployments, and job loss can also have long-lasting traumatic effects.

“When you go through a crisis, you get broken apart, and you’re able to put yourself back together. When you live through a trauma, you’re shattered, and you can’t put the pieces back together, not the same way they were.””

Officer Marlene Tully, in Policy Research Associates’ Trauma-Informed Care training video

Using a Trauma-Informed Approach

According to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, “a trauma-informed approach begins with understanding the physical, social, and emotional impact of trauma on the individual, as well as on professionals who help them.”11 This approach can be used to guide professionals in developing practices, services, and policies that promote recovery and healing for people in the justice system who have been impacted by trauma.

The following content in this section is adapted from SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach.12

When adopting a trauma-informed approach, everyone in the system or agency should be able to:

- Realize how widespread trauma is, not just among people in the criminal justice system, but also among staff;

- Recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma among people under supervision and in treatment, or who are providing supervision and treatment services;

- Respond by developing and implementing trauma-informed policies and practices through leadership, training, and resources; and

- Resist retraumatizing people in the justice system and staff who work with them.

Rather than a prescriptive set of programs or practices, a trauma-informed approach involves the following key principles:

- Safety: physical and emotional safety for all;

- Trustworthiness and Transparency: trustworthiness and transparency across an organization or agency;

- Peer Support: peer support from people with experience in the criminal justice system;

- Collaboration and Mutuality: reduction of power differentials among staff and people in the justice system through collaboration and shared decision making;

- Empowerment, Voice, and Choice: encouragement for people to be empowered to speak up on their own behalf, advocate for their needs, and make decisions about how those needs are met to build resilience and self-advocacy; and

- Cultural, Historical, and Gender Issues: cultural humility and responsiveness in various forms, including racial, ethnic, and cultural.

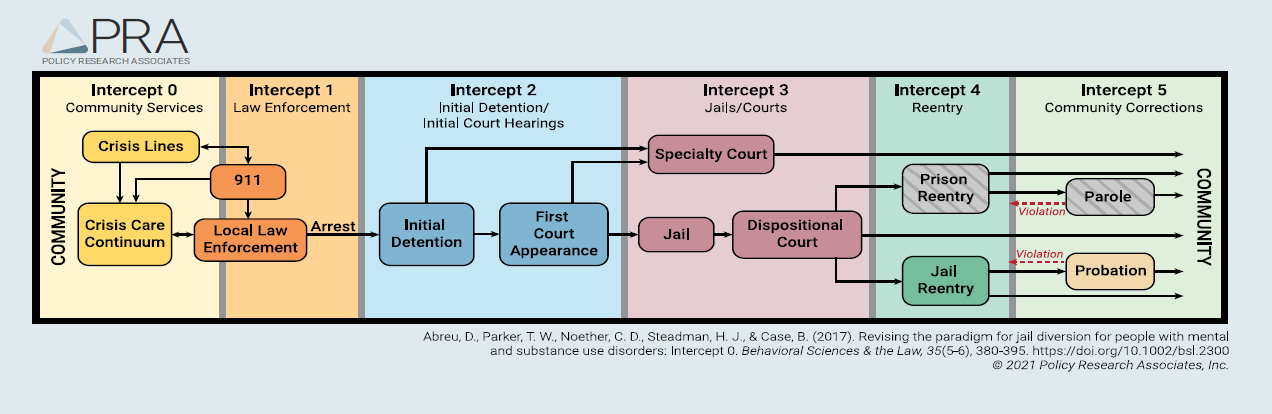

The Sequential Intercept Model

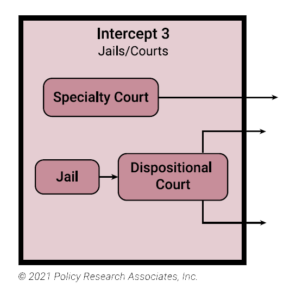

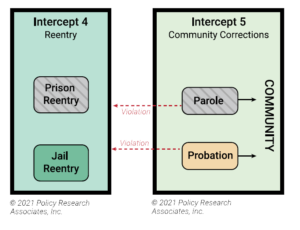

The Sequential Intercept Model (SIM)13 provides a framework for understanding how most people move through the criminal justice system (see Figure 1. Policy Research Associates’ Sequential Intercept Model). The SIM identifies six criminal justice intercepts where interventions can be implemented to prevent further involvement in the justice system. Communities can use the SIM as a strategic planning tool to understand how people interact with the criminal justice system, identify service gaps, and determine priorities for improvements in each intercept and system wide.

Figure 1. Policy Research Associates’ Sequential Intercept Model

Identifying Opportunities to Implement a Trauma-Informed Approach with the Help of the Sequential Intercept Model

To foster a more trauma-informed local criminal justice system, criminal justice and behavioral health professionals can use the SIM to identify opportunities that exist to develop cross-trainings, enhanced communication strategies, and trauma-informed policies and practices at each intercept. Staff at each intercept should have an understanding of the prevalence and impact of trauma, explore which evidence-based trauma-specific services exist for their participants, and examine how their current workplace environment promotes a sense of safety for all.

After determining where gaps exist, a jurisdiction then, for example, may decide to implement practices such as incorporating a trauma-specific screening tool into their intake processes or adding a peer support specialist to a specialty court team who can use their lived experience to promote a sense of hope and help to engage participants. The SIM can also help to identify which stakeholders must be involved to implement the changes and the potential impact such changes could have on the justice system and the people who encounter it.

Jurisdictions can also use the SIM to ensure trauma-informed practices and policies are being implemented across the system. Taking a system-wide approach to implementing trauma-informed care can ensure that there are opportunities to prevent people from being retraumatized at any given intercept and from cycling through the justice system.

Below is one example of what a trauma-informed approach can look like when the community leaders (e.g., chief judge, sheriff, chief of police) have decided to implement it across the local justice system. This example follows “John Doe,” who encounters a co-responder team (i.e., an officer and crisis professional) in a shopping mall parking lot with stolen merchandise. The team was called to the scene after receiving a 911 call from a store shopper who saw a young, Black man talking to himself and stealing headphones. Given the description of John’s mental state and behavior provided by the caller, dispatch coded the call as a mental health call and dispatched the local co-responder team to evaluate the scene. Even before the co-responder team reaches John Doe, they have in mind that he could be experiencing a behavioral health crisis, may have a trauma history, and may be fearful of police given the history of negative police interactions in Black American communities.

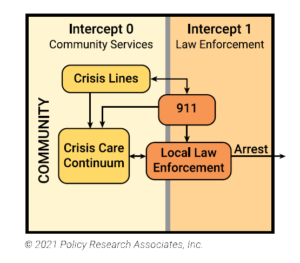

Intercepts 0 and 1: Community Services and Law Enforcement

Crisis services, including law enforcement response and community supports, provide the initial opportunity for adopting trauma-informed policies and practices for people who are at risk of becoming involved in the system. It is also the first opportunity for people to be retraumatized if trauma-informed policies and practices are not implemented.

Trauma-informed approach in practice (intercept 1)

Trauma-informed approach in practice (intercept 1)

- A co-responder team with both an officer and crisis professional responds to the emergency mental health call. Once on the scene the co-responder team clears the scene for immediate safety risks and makes themselves visible to John Doe. When addressing John Doe, the co-responder team asks them what name they prefer and what their pronouns are. The team has been approved to wear plain clothes, not police uniforms, to reduce any stress Mr. Doe may have from previous associations with police encounters and to reduce power differentials between them and Mr. Doe. The officer and crisis professional also take a relaxed posture with him, informing Mr. Doe of their names, and reminding him that they are there to understand what is happening, so that they can ensure he and everyone around him are safe.

- When checking the Computer-Aided Dispatch system, the officer determines that Mr. Doe has an outstanding warrant and therefore must be taken into custody. The officer and crisis professional calmly explain to Mr. Doe why he is being arrested and where he is being transported to. This information-sharing explanation before an action occurs helps to promote trustworthiness between Mr. Doe and the first responders while ideally lessening the anxiety associated with the arrest process. Based on the police department’s handcuffing policy, the team provides him with the choice as to whether he prefers to be handcuffed in front or behind his back. The team also asks Mr. Doe which side of the car he prefers to ride on and what radio station he prefers to listen to, recognizing that voice and choice are key principles in a trauma-informed approach.

- Because of their open communication, on the drive to the jail, Mr. Doe informs the co-responder team that he is scared to go to jail because in a nearby jurisdiction, he was “beaten the last time he was in jail when he fought back during a strip search.”

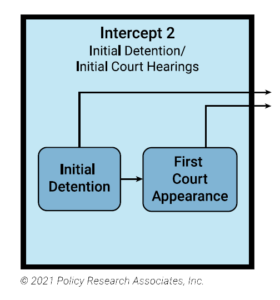

Intercepts 2 and 3: Initial Detention and Jails/Courts

First appearance courts, jail detention, and specialty courts present opportunities to adopt a trauma-informed approach pretrial. An array of professionals from different agencies work in these intercepts, underscoring the importance of the communication and cross-training needed for implementing trauma-informed practices.

Trauma-informed approach in practice (intercepts 2 and 3)

Trauma-informed approach in practice (intercepts 2 and 3)

- Continuing with trauma-informed practices relating to safety, the jail booking officer asks the co-responder team if there is anything that the jail needs to know about Mr. Doe’s circumstances to help make sure he and the corrections officers remain safe. With his permission, the officer and crisis professional tell the booking officer that Mr. Doe shared that he is afraid of being hurt at the jail and why. Given this information, the booking officer requests that a behavioral health professional meet with Mr. Doe to explain the search procedure and provide emotional support. The booking officer, along with all his correction officer colleagues, have received training in de-escalation and recognizing signs and symptoms of anxiety, fear, and mood dysregulation.

- Later, the booking officer explains to Mr. Doe that they have some administrative procedures to go through, and after that, they escort him to his housing area. The booking officer also explains that Mr. Doe can call his lawyer and case manager later in the afternoon. By providing this information to Mr. Doe, the booking officer demonstrates the principle of trustworthiness and

transparency.

transparency. - In court, the judge asks Mr. Doe where he lives and works. During this conversation, the judge finds out that he needs housing, so the judge connects him to a court social worker for assistance. The next day in the jail, the social worker facilitates a separate conversation with Mr. Doe and a peer support specialist to discuss housing options. The social worker and peer support specialist also ask him which housing options best support his needs. Having peer support and encouraging Mr. Doe to make his own choice incorporates two key principles of a trauma-informed approach.

Intercepts 4 and 5: Reentry and Community Corrections

Incorporating a trauma-informed approach into reentry services and community supervision can be an important way to better engage participants and involve them in the reentry planning process. This sets the stage for positive outcomes such as reduced recidivism and behavioral health recovery. Additionally, because reentry planning should begin prior to a person’s release, trauma-informed practices must also be incorporated into case management and in-reach by community-based providers.

Trauma-informed approach in practice (intercept 4)

- Later that week, the jail-based behavioral health provider conducts a behavioral health and criminogenic risk and needs assessment with Mr. Doe to assess his reentry planning needs. The behavioral health provider then holds a meeting with him, the peer support specialist, and other relevant criminal justice and behavioral health partners to discuss and develop his collaborative comprehensive case plan.

- Given that Mr. Doe’s assessment shows he has a mental illness and a co-occurring substance use disorder, his provider determines that he should continue to receive behavioral health treatment once released from jail. Mr. Doe is specifically asked if he had a previous provider who he would like to continue to work with. If he does not, he is asked if he has any preferences regarding the gender, race, or ethnicity of his future outpatient therapist.

- Staff also explain to Mr. Doe what his criminogenic risk and needs assessment results are and how the results shape recommendations about which services or interventions could be most helpful for him. At this meeting, the providers engage Mr. Doe and ask him to share his ideas, concerns, and needs. This gives him the ability to advocate for himself, be part of the decision-making process about his services, and develop his own treatment goals.

Trauma-informed approach in practice (intercepts 4 and 5)

• Prior to being released, Mr. Doe’s assigned probation officer, who has specialized training in working with people with behavioral health needs, receives and reviews his case plan. Upon being released from custody, Mr. Doe’s probation officer and the peer specialist meet him at the jail, bring him clean clothes, take him for a meal, and drop him off at the housing that the court social worker and others have arranged for him. Before leaving, the probation officer asks Mr. Doe if he has any set commitments during the week that could interfere with the reporting schedule in an effort to foster transparency, choice, and success with supervision conditions.

• Mr. Doe shares with his probation officer that he is enrolled in a GED class that meets in the morning and would prefer an afternoon reporting time. The probation officer then works with him to schedule afternoon appointments that work for them both. One probation condition includes weekly outpatient therapy. The probation officer collaborates with Mr. Doe and his therapist to receive updates on his attendance and to develop a relapse prevention plan.

Additional Resources

For more information about implementing a trauma-informed approach in the criminal justice system, see the following resources:

Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach is a report from SAMHSA that provides guidance for implementing a trauma-informed approach along 10 key domains.

Responding to Individuals in Behavioral Health Crisis Via Co-Responder Models is a brief that highlights various co-responder models.

SAMHSA’s Essential Components of Trauma-Informed Judicial Practice is an issue brief that provides information, specific strategies, and resources for court staff and judges.

Trauma-Informed Approaches for Programs Serving Fathers in Re-Entry: A Review of the Literature and Environmental Scan is a report that provides information about trauma among fathers returning to the community after incarceration and evidence-based, trauma-specific services that have been shown to support this population.

Trauma-Informed Care Across the Intercepts is a webinar from The Council of State Governments Justice Center, which provides an overview of the core principles of trauma-informed care and best practices for using it at each intercept point within the SIM.

Trauma-Informed Corrections is a chapter in a book that defines trauma and trauma-related disorders, the prevalence of traumatic experiences among people involved in the criminal justice systems, and how the criminal justice system could work to become more trauma informed.

Endnotes

1. Emily Widra, “No Escape: The Trauma of Witnessing Violence in Prison,” Prison Policy Initiative, December 2, 2020, accessed April 12, 2021, https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/12/02/witnessing-prison-violence/.

2. Bonnie L. Green et al., “Trauma Exposure, Mental Health Functioning, and Program Needs of Women in Jail,” Crime & Delinquency 51, no. 1 (2005): 133–151.

3. Nancy Wolff et al., “Trauma Exposure and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Among Incarcerated Men,” J Urban Health 91 no. 4 (2014): 707–719, doi:10.1007/s11524-014-9871-x.

4. Nancy Wolff et al., “Patterns of Victimization Among Male and Female Inmates: Evidence of an Enduring Legacy,” Violence and Victims 24, no. 4 (2009): 469–84, doi:10.1891/0886-6708.24.4.469.

5. In 2018, for example, about 1 in 20 Black men, ages 35-39, were in state or federal prison. See John Gramlich, “Black Imprisonment Rate in the U.S. has Fallen by a Third Since 2006,” Pew Research Center, May 6, 2020, accessed April 14, 2021, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/05/06/share-of-black-white-hispanic-americans-in-prison-2018-vs-2006/.

6. “According to Pérez Benítez et al. (2014), Black Americans report higher rates of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) compared to White Americans. For example, a study by Alcántara, Casement, and Lewis-Fernández (2012) reported a PTSD prevalence rate of 8.6–8.7% for African Americans, compared to 6.5–7.9% for White individuals. In examining the factors that may contribute to these differing prevalence rates of PTSD, Carter (2007) highlighted the influence of race-based trauma. According to the author, race-based trauma reflects the experience of trauma-related symptoms, such as anxiety, intrusive thoughts, and flashbacks, that are exacerbated by the chronic experience of systemic racism.” See Steven Kniffley, “Institutionalized Mental Trauma and Generational Transmission,” in Black Males and the Criminal Justice System, ed. Jason M. Williams and Steven Kniffley (New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 2019) 109–120; “What is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder,” American Psychiatric Association, accessed July 15, 2021, https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd.

7. Sheryl P. Kubiak, Stephanie S. Covington, and Carmen Hiller, “Trauma-Informed Corrections,” in Social Work in Juvenile and Criminal Justice System 4th Edition, ed. David Springer and Albert Roberts, (Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Pub Ltd, 2017); Jill Levenson & Gwenda Willis, “Implementing Trauma-Informed Care in Correctional Treatment and Supervision,” Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma 28, no. 4 (2019): 481–501.

8.SAMHSA, Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach (Rockville, MD: SAMHSA, 2014), https://store.samhsa.gov/product/SAMHSA-s-Concept-of-Trauma-and-Guidance-for-a-Trauma-Informed-Approach/SMA14-4884.

9. Simran Chaudhri et al., “Trauma-Informed Care: A Strategy to Improve Primary Healthcare Engagement for Persons with Criminal Justice System Involvement,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 34, no. 6 (2019): 1048–1052.

10. “Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, accessed July 31, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/fastfact.html CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fviolenceprevention%2Fchildabuseandneglect%2Faces%2Ffastfact.html; Sarah R Holley et al., “The Relationship Between Emotion Regulation, Executive Functioning, and Aggressive Behaviors,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 32, no. 11 (2017): 1692–1707.

11.“Using a Trauma-Informed Approach,” Office for Victims of Crime Training and Technical Assistance Center, accessed May 21, 2021, https://www.ovcttac.gov/taskforceguide/eguide/4-supporting-victims/41-using-a-trauma-informed-approach/

12. SAMHSA, Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach.

13. Dan Abreu et. al., “Revising the Paradigm for Jail Diversion for People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders: Intercept 0,” Behavioral Health Sciences and the Law 35, no. 5-6 (2017): 380–395.

Project Credits

Writing: Rachel Lee, CSG Justice Center and Dr. Lisa Callahan, PRA

Advising: Dr. Allison Upton and Sarah Wurzburg, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Darby Baham and Emily Morgan, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Web Development: Catherine Allary

Public Affairs: Aisha Jamil, CSG Justice Center

The Council of State Governments Justice Center prepared this resource with support from the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) under grant number 2016-MU-BX-K003 & 2019-MO-BX-K001. The opinions and findings in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice or the members of The Council of State Governments. The supporting federal agency reserves the right to reproduce, publish, translate, or otherwise use and authorize others to use all or any part of the copyrighted material in this publication.

About the CSG Justice Center: The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center is a national nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that combines the power of a membership association, representing state officials in all three branches of government, with policy and research expertise to develop strategies that increase public safety and strengthen communities. For more information about the CSG Justice Center, visit www.csgjusticecenter.org.

About Policy Research Associates: Policy Research Associates, Inc. (PRA) is a certified Women-Owned Small Business that is a national leader in behavioral health and research. PRA offers four core services that help individuals with behavioral health needs achieve recovery. In partnership with their close partner non-profit, Policy Research, Inc., they offer technical assistance, training, research, and policy evaluation services. For more information about the PRA, visit www.prainc.com.

Suggested Citation: Rachel Lee and Dr. Lisa Callahan, Trauma-Informed Approaches Across the Sequential Intercept Model. (New York: The Council of State Governments Justice Center, 2022).

About the authors

From 911 to 988: Salt Lake City’s Innovative Dispatch Diversion Program Gives More Crisis Options

From 911 to 988: Salt Lake City’s Innovative Dispatch Diversion Program Gives More Crisis Options

A three-digit crisis line, 988, launched two years ago to supplement—not necessarily…

Read More Matching Care to Need: 5 Facts on How to Improve Behavioral Health Crisis Response

Matching Care to Need: 5 Facts on How to Improve Behavioral Health Crisis Response

It would hardly be controversial to expect an ambulance to arrive if…

Read More Taking the HEAT Out of Campus Crises: A Proactive Approach to College Safety

Taking the HEAT Out of Campus Crises: A Proactive Approach to College Safety

The sharp rise in school shootings over the past 25 years has…

Read More From 911 to 988: Salt Lake City’s Innovative Dispatch Diversion Program Gives More Crisis Options

From 911 to 988: Salt Lake City’s Innovative Dispatch Diversion Program Gives More Crisis Options

A three-digit crisis line, 988, launched two years ago to supplement—not necessarily…

Read More Matching Care to Need: 5 Facts on How to Improve Behavioral Health Crisis Response

Matching Care to Need: 5 Facts on How to Improve Behavioral Health Crisis Response

It would hardly be controversial to expect an ambulance to arrive if…

Read More