Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program Overview

Updated September 2023

JUSTICE & MENTAL HEALTH COLLABORATION PROGRAM

The Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program (JMHCP) provides grants directly to states, local governments, and federally recognized Indian tribes to improve responses to people with mental health conditions who are involved in the criminal justice system. JMHCP funding requires collaboration with a mental health agency.

SUCCESS BY THE NUMBERS

- Since 2006, JMHCP funded 774 awardees across 49 states, Washington, DC, and two U.S. territories (including American Samoa and Guam).

- $251.2 million has been awarded, and in 2022, maximum award amounts were $550,000.

- Communities across the country have used JMHCP funding to implement systemwide reforms that span first contact with the justice system to reentry and return to the community. This includes funding for crisis stabilization units, mental health courts, universal mental health screening and assessment in jail, permanent supportive housing, and community corrections mental health caseloads.

- The program supports 15 Law Enforcement-Mental Health Learning Sites who serve as peer resources to grantees and communities across the country. The current learning sites are:

- Arlington Police Department (MA)

- Bexar County Sheriff’s Office (TX)

- Harris County Sheriff’s Department (TX)

- Houston Police Department (TX)

- Los Angeles Police Department (CA)

- Madison County Sheriff’s Office (TN)

- Madison Police Department (WI)

- Miami-Dade County Police Department (FL)

- Portland Police Department (ME)

- Salt Lake City Police Department (UT)

- Tucson Police Department (AZ)

- University of Florida Police Department

- Wichita Police Department (KS)

- Yavapai County Sheriff’s Office (AZ)

- Denver Police Department (CO)

-

Launched in 2021, the Connect and Protect: Law Enforcement and Behavioral Health Response Program is a funding opportunity available under the JMHCP program. Awards help communities improve collaborative law enforcement responses to people with behavioral health needs. This program aims to reduce unnecessary law enforcement contact, connect people to needed treatment and supports, and improve public safety.

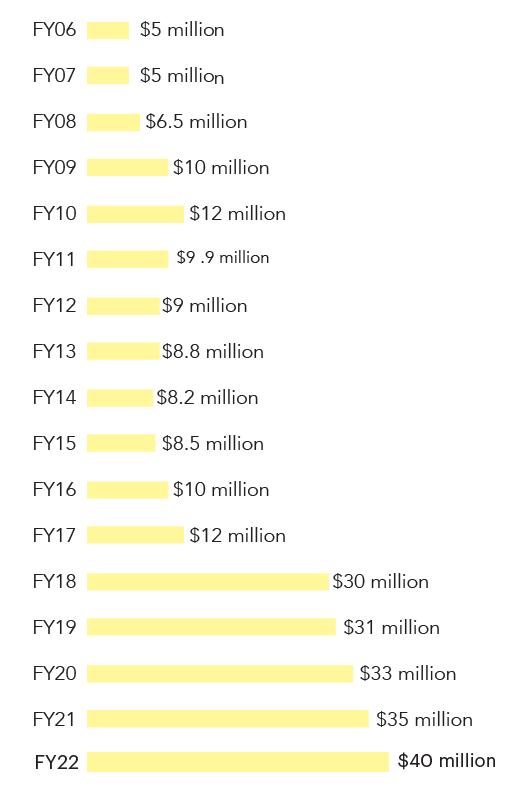

FUNDING AMOUNTS

SITE-BASED PROJECTS: A CLOSER LOOK

THE COLORADO DIVISION OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE

Using JMHCP funds, this division is improving the state’s crisis services by developing integrated dispatch response to 911 and 988 mental health calls; increasing training for 911 call takers and dispatchers; updating and disseminating protocols for emergency calls related to mental health; and establishing mental health first responders as a fourth dispatch option in addition to law enforcement, fire, and emergency medical services. The division is also working with partners to fine-tune dispatch protocols and is creating an online tool that will connect police-mental health collaboration programs around the state.1

BOSTON, MA

The Boston Police Department established a co-responder team that fielded more than 1,000 mental health calls between 2011 and 2016. Of those calls for service, only 9 resulted in arrest. Instead, with the help of the co-responding clinician, many of the calls (approximately 400 calls) were able to be resolved on the scene.2

JMHCP: SUPPORT TO THE FIELD

In addition to directly supporting grantees, JMHCP also provides resources and hands-on consulting to all communities whether or not they are grantees. Below are examples of that support.

|

SYSTEMS WIDE |

• The Center for Justice and Mental Health Partnerships offers free consultation to any community that requests help to support their efforts in diverting people away from the criminal justice system and safely connecting them to treatment and supports. Assistance is tailored to meet the needs of the jurisdiction and includes virtual and in-person consultation, connection with subject matter experts, peer-to-peer learning, and virtual events. . • A brief on peer support specialists describes how they are being hired in a variety of criminal justice settings, including in crisis stabilization units and pretrial diversion programs, to use their training and lived experience with behavioral health conditions and the criminal justice system to support clients with similar histories. . • Collecting, matching, and storing behavioral health and criminal justice data are some of the most significant challenges that jurisdictions face. This checklist and accompanying brief help jurisdictions to develop central data warehouses that can be used to store data and guide system wide improvements. |

|

INTERCEPTS 0 AND 1: Law Enforcement and Community-Based Supports and Crisis Services

|

• The Police-Mental Health Collaboration (PMHC) framework is intended to help jurisdictions advance comprehensive, agency-wide responses to people with mental health needs in partnership with behavioral health systems. The framework is accompanied by the PMHC toolkit and the PMHC self-assessment tool. The tool walks agencies through a series of questions to assess the status of their efforts and generates a unique action plan to strengthen that work.

|

|

INTERCEPT 2: Initial Detention and Court Hearings |

• A brief on systems-wide behavioral health diversion interventions and accompanying court and jail fact sheets outline key components and implementation steps toward developing effective diversion strategies.

|

|

INTERCEPT 3: Courts and Correctional Facilities |

• The Stepping Up Strategy Lab is an interactive tool that features examples from nearly 120 communities across the country working to reduce the number of people with serious mental illnesses in their jails. The tool was created to help policymakers identify strategies they can adopt in their local communities to improve outcomes for this vulnerable population. Stepping Up Innovator counties lead the nation in bringing about meaningful change in the movement to reduce the number of people with behavioral health needs in local jails through successfully collecting and applying data to inform decision-making.

|

|

INTERCEPT 4: Reentry |

• Improving access to safe and affordable housing is integral to any efforts to reduce peoples’ involvement in the criminal justice system and establishing stability in the community. Action Points: Four Steps to Expand Access to Housing for People in the Justice System with Behavioral Health Needs highlights steps state leaders can take to increase housing opportunities and improve justice and health outcomes.

|

|

INTERCEPT 5: Community Corrections |

• Probation mental health caseloads, also called specialized caseloads, are implemented to help ensure that people with behavioral health conditions can successfully complete community supervision. This includes implementing smaller caseloads and less restrictive supervision requirements to account for the possibility that symptoms of behavioral health needs (such as relapse) can lead to technical violations or new arrests. Communities with specialized caseloads can see fewer arrests, fewer days in jail, and improved mental health outcomes for people on probation. This brief provides five key practices for successful implementation of these programs.

|

JMHCP SITES: INTERVENTIONS, DESCRIPTIONS, & APPROACHES

Intercept 0-1: Community Services, Law Enforcement

Below is a list of some of the interventions that jurisdictions can use at intercepts 0 and 1 (also known as points) in their criminal justice system.3

This list is not exhaustive, and many can be implemented at various points in the system.

|

Intervention |

Description | Program Rationale4 |

Example Site |

| CASE MANAGEMENT FOR “HIGH UTILIZERS” | Officers—often in collaboration with mental health professionals—connect people with mental health needs who have repeated interactions with law enforcement to mental health services and community resources. | Case management teams are designed to address the needs of people who frequently utilize multiple systems. Clinician and officer teams (or sometimes just clinicians) provide outreach and follow-up care to . . . people to provide engagement, linkage to services, and monitoring.5 | • SITE: Houston (TX) Police Department • STATUS: Law Enforcement-Mental Health Learning Site • DESCRIPTION: In 2020, 79 clients were served through the Chronic Consumer Stabilization Initiative (CCSI)—a clinical case management program. Compared to one year prior to CCSI participation, clients saw a 72 percent reduction in emergency services contact, including hospital and law enforcement (cost savings $46,881).6 |

| CO- RESPONDER TEAMS | Specially-trained officers and mental health crisis workers respond to mental health calls for service together and link people who have mental illnesses to appropriate services. | Co-responder teams improve collaboration between police and mental health providers and may reduce officer time on scene, emergency department transports, and repeat calls for service.7 | • SITE: Boulder County, CO • STATUS: FY2016 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: From January 2018 to December 2019, the Boulder Early Diversion Get Engaged (EDGE) program in Colorado diverted 829 people. Based on 2016 cost analysis, the co-responder team program saves the county approximately $3 million annually by reducing incarcerations and hospitalizations.8 |

| CRISIS STABILIZATION UNITS (CSUs) | CSUs provide short-term access to emergency psychiatric services for people experiencing crises, and often provide constant supervision throughout a person’s stay. | CSUs offer an alternative to jail or crowded emergency departments by being accessible, providing quick intake and drop-off procedures for law enforcement, and specializing in care for people with mental illnesses and/or substance use disorders.9 | • SITE: Athens-Clarke County, GA • STATUS: FY2019 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: Athens-Clarke County partners with the local behavioral health crisis center, which features a 24/7 hour walk-in unit staffed by certified peers; a temporary observation unit, where people can stay for up to 23 hours; and a crisis stabilization unit that discharges 100 percent of the people it receives to safe environments with referrals to community care.10 |

| CRISIS INTERVENTION TEAMS (CIT) | Agencies provide mental health training to patrol officers. Some agencies also create teams of these specially trained officers to respond to mental health calls. | CIT improves officer knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in responding safely and effectively to mental health crisis calls … CIT also increases linkages to services for people with mental illnesses.11 | • SITE: Gresham County, OR • STATUS: JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: In Gresham County, less than 6 percent of mental health calls that were responded to by a CIT-trained officer result in jail, significantly less than than mental health calls responded to by an officer without CIT training.12 |

| MOBILE CRISIS TEAMS | Mental health professionals who respond to calls for service, sometimes at the request of law enforcement and divert people from unnecessary jail bookings and/or emergency rooms. | Research has shown that mobile crisis teams can increase use of community-based mental health services and increase hospitalization after receiving emergency department-based services.13 | • SITE: Village of Orland Park, IL • STATUS: FY2019 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: Over a two-month period in 2020, the Village of Orland Park Police Department mobile crisis response unit responded to 61 mental health calls. Fifty-six percent of these calls were resolved at the scene, with only 3 percent resulting in arrest and 13 percent resulting in emergency room visits.14 |

JMHCP SITES: INTERVENTIONS, DESCRIPTIONS, & PROMISING APPROACHES

Intercept 2: Initial Detention, Court Hearing

Below is a list of some of the interventions that jurisdictions can use at different intercepts (also known as points) along their criminal justice system. This list is not exhaustive and, while interventions are only listed at one intercept, many can be implemented at various points in the system.

|

Intervention |

Description | Rationale |

Example Site |

| ACCESS TO MENTAL HEALTH LIAISIONS (also known as navigators) | Liaisons support people through the court process or in reentry planning in a number of ways, including conducting on-site mental health screens, expediting referrals, facilitating “warm hand-offs” to services, re-connecting clients with treatment providers, and assisting with benefits enrollment.15 | Liaisons can help quickly screen for mental health needs and connect people to treatment and other stabilizing services. | • SITE: Van Buren County, MI • STATUS: FY2019 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: The county’s Adult Recovery Court Program provides behavioral health services and specialized court services to participants, including a clinical liaison, a case manager, and two peer support specialists. The liaison uses validated risk and needs assessments to determine program placement, as well as supervision and treatment plans for court participants. |

| HOLISTIC DEFENSE | Defense counsel work with case managers and other social service staff to address a client’s court case as well as underlying circumstances that contribute to their contact with the criminal justice system, such as mental illness, substance use, and housing needs. | Holistic defense has been shown to reduce clients’ likelihood of incarceration and shorten expected sentence length without increasing the risk to public safety.16 | • SITE: Bexar County, TX • STATUS: JMHCP-funded pretrial analysis • DESCRIPTION: Mental health defenders within the Bexar County Public Defender’s office work with a case manager to identify community-based placements and resources for clients. The office reports that, from 2015 to 2017, this defense model saved 6,255 days of incarceration and improved client adherence to treatment.17 |

| MENTAL HEALTH DIVERSION (also known as pre- or post-booking diversion, alternatives to detention, or alternatives to incarceration) | Mental health diversion programs provide connection to community-based treatment in lieu of incarceration. These programs can be entered into pre- booking or post-booking.18 Further, some programs require a plea, while others do not. | These programs have been shown to reduce jail time and the mental health needs of participants without increasing public safety risk.19 | • SITE: Douglas County, KS • STATUS: Stepping Up Innovator • DESCRIPTION: The county employs a system-wide approach, including use of a crisis intervention team and a co-responder team, jail screening and assessment, and a behavioral health campus to provide crisis services and supportive housing. County data show a 56 percent reduction in jail bookings for people with serious mental illnesses from 2014 to 2018.20 |

| SPECIALIZED PRETRIAL SERVICES PROGRAM | People are released to pretrial services programs in lieu of incarceration, where they are supervised by staff trained to work with people who have mental illnesses. Under this community supervision, a client may receive treatment voluntarily or as a condition of release. | The “essential elements” of pretrial programs for people with mental health conditions include staff training, screening for mental health needs, and connection to treatment provided with the least restrictive conditions necessary to assure appearance in court.21 | • SITE: Muskegon County, WI • STATUS: FY2019 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: The county jail uses a risk and needs triage tool and shares results with other partners to determine pretrial release and supervision levels for people on probation. A community mental health worker also helps coordinate post-release services, including for opioid addiction. The project is expected to decrease the average time to the first post-release service by one week and increase the number of people receiving clinical assessments. |

| UNIVERSAL SCREENING FOR MENTAL HEALTH AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS | Corrections agencies conduct a standardized, validated screening for mental health and substance use conditions with every person who is booked into their facilities. | Implementing universal screening is the first step to ensuring that all people needing treatment are identified and connected to treatment in the facility and upon release.22 | • SITE: Hinds County, MS • STATUS: FY2017 JMHCP Collaborative County grantee • DESCRIPTION: Everyone entering the Hinds County Detention Center are screened with the Mental Health Screening Form III, and the Texas Christian University Drug Screen V. From October 2018 to January 2019, they found that 43 percent of people had a positive mental health screen. Further, they stayed longer in the jail than their counterparts, and they had low rates of connection to community-based treatment upon reentry. This data helped the county to begin planning new strategies to increase connections to care upon release.23 |

JMHCP SITES: INTERVENTIONS, DESCRIPTIONS, & PROMISING APPROACHES

Intercept 3: Jails, Courts

Below is a list of some of the interventions that jurisdictions can use at different intercepts (also known as points) along their criminal justice system. This list is not exhaustive and, while interventions are only listed at one intercept, many can be implemented at various points in the system.

|

Intervention |

Description | Rationale |

Example Site |

| IN-REACH SERVICES BY COMMUNITY-BASED PROVIDERS | Staff from community-based health, social services, and/or homelessness services have easy access to, or are embedded in, correctional facilities to assess the treatment and housing needs of the people in custody. They also work with facility staff to help ensure treatment and services are continued upon release as part of reentry planning. | In-reach services can improve the services provided in correctional facilities and increase continuity of care by connecting people with organizations and service providers prior to release who they can continue working with upon reentry.24 | • SITE: Flagler County, FL • STATUS: FY2020 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: The Flagler County Sheriff’s Office is partnering with the local mental health provider, EPIC Behavioral Health, to embed a clinician in the jail. The clinician will be able to provide cognitive behavioral therapy to people while they are incarcerated. After they are released, the clinician can also help to connect clients to medication assisted treatment (MAT), as well as housing, education, and employment supports. |

| JAIL-BASED BEHAVIORAL HEALTH PROGRAMMING | Corrections agencies provide mental health and substance use treatment to people with behavioral health needs, including appropriate medication and cognitive behavioral interventions. | Providing holistic behavioral health services, including MAT, to people in jail can improve individual health both in the facility and upon their return to the community.25 | • SITE: Franklin County, MA • STATUS: FY2016 JMHCP Expansion grantee • DESCRIPTION: People in the jail receive integrated mental health and substance use services (such as MAT, Seeking Safety, Acceptance Commitment Therapy, and Motivational Interviewing) and are connected to community-based services upon release. In 2017, of the people released to the community, 98 percent were connected to health insurance, 56 percent had outpatient therapy appointments, and 20 percent were connected to MAT.26 |

| MENTAL HEALTH COURTS (also known as specialty courts, problem-solving courts, collaborative courts, and specialized dockets) | In contrast to the traditional court process, mental health courts employ a collaborative, interdisciplinary team approach where the judge, attorneys, treatment providers, and others such as peers, support the person with community-based treatment and supervision in lieu of typical criminal prosecution. | Successful specialty courts, including mental health courts, can reduce recidivism, improve connections to treatment, and be cost-effective.27 | • SITE: Yolo County, CA • STATUS: FY2019 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: Criminal justice and behavioral health agencies in Yolo County are working to double the capacity of the current mental health court (MHC). The MHC serves people with severe mental illnesses, including people with co-occurring substance use conditions who are facing criminal charges linked to a felony offense, and provides them with a treatment plan and connection to services. |

| SPECIALIZED BEHAVIORAL HEALTH TRAINING FOR CORRECTIONS OFFICERS | Corrections officers receive training on mental illnesses and/or substance use disorders to improve their understanding of, and ability to, effectively supervise people with behavioral health needs. | CIT—one of the most common forms of specialized training—has been shown to provide corrections officers with “a higher degree of comfort when encountering people with signs of mental illness… and more confidence to defuse or de-escalate situations.”28 Other trainings, such as Mental Health First Aid for public safety and Motivational Interviewing, have also been effectively adapted for corrections officers. | • SITE: Minnesota Department of Corrections (DOC) • STATUS: FY2016 JMHCP Expansion grantee • DESCRIPTION: The DOC expanded its CIT in Prisons project to provide training to field staff including supervised release agents, probation agents, sentence-to-serve crew leaders, and support staff. A survey of CIT training participants found that 99 percent expected to use the skills learned in training and about 40 percent estimated they would use the skills at least weekly.29 |

JMHCP SITES: INTERVENTIONS, DESCRIPTIONS, & PROMISING APPROACHES

Intercept 4: Reentry

Below is a list of some of the interventions that jurisdictions can use at different intercepts (also known as points) along their criminal justice system. This list is not exhaustive and, while interventions are only listed at one intercept, many can be implemented at various points in the system.

|

Intervention |

Description | Rationale |

Example Site |

| ACCESS TO BENEFITS NAVIGATORS | Trained professionals and paraprofessionals help people awaiting release complete applications and enroll in benefits such as Medicaid, health insurance, Supplemental Security Income(SSI)/Social Security Disability Insurance(SSDI), food stamps, housing, and services specifically for veterans. | Connecting people to benefits helps them access supports, such as health care, which can result in improved wellbeing and may result in cost savings. In fact, estimates from North Carolina (a non-expansion state) indicate “potential savings of $178,000 for each incarcerated person enrolled in Medicaid.”30 | • SITE: Alcovy Circuit Mental Health Court, GA • STATUS: FY2015 JMHCP Expansion grantee • DESCRIPTION: The Court hired benefits navigators31 to improve access to disability benefits. The navigators were able to decrease the average time to approval for benefits from several months to six to eight weeks.32 |

| ACCESS TO PEER SUPPORT | Peers are people who have lived experience of the behavioral health and/or and criminal justice systems and who have been trained to support others by delivering a range of interventions, such as self-management skill-building, leading support groups, and mentorship. | “Peer specialists are equally effective as other health care providers at stabilizing clients and perhaps more effective at quickly engaging clients who are most resistant and/or alienated from the health care system… [they] reduce internalized stigma and promote empowerment and inclusion…”33 | • SITE: City of Wilmington, NC • STATUS: FY2016 JMHCP Expansion grantee • DESCRIPTION: Wilmington expanded their adult reentry program to include a peer support specialist. The peer specialist helps program staff improve outcomes for women with co-occurring substance use and mental health disorders through case management, integrated treatment, parenting skills classes, family counseling, and increased recovery support, among other services. |

| ASSERTIVE COMMUNITY TREATMENT (ACT)/ FORENSIC ACT (FACT) AND FORENSIC INTENSIVE CASE MANAGEMENT (FICM) | Multidisciplinary teams of mental health professionals deliver long term, highly intensive, comprehensive, and mobile, community-based services to people with serious mental illnesses (SMI) or co-occurring disorders for whom other forms of traditional mental health treatment has not been effective. | These interventions have been shown to reduce a person’s psychiatric hospitalizations, increase housing stability, and improve quality of life and functioning while reducing their recidivism and parole technical violations.34 | • SITE: Monroe County, NY • STATUS: FY2020 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: The county established a Forensic Intervention Team (FIT), which includes embedded clinicians within law enforcement and provides on-scene crisis intervention, mental health screens, and post-crisis care, including case management and referrals for services. The county office of mental health also has a collaborative partnership with community mental health treatment agencies, including a commitment to accept referrals from FIT and offer rapid access to care. |

| PERMANENT SUPPORTIVE HOUSING | Permanent supportive housing couples permanent housing with flexible treatment and support services to help stabilize people who are chronically homeless and who often have serious mental illnesses and other complex health and social service needs. | Permanent supportive housing has been shown to reduce contact with the criminal justice system, homeless shelter stays, and use of emergency health services.35 | • SITE: Sonoma County, CA • STATUS: FY2018 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: The county is focused on providing housing and supports in the community during the pretrial period to people with mental health conditions and co-occurring substance addictions, including opioid addictions. An eight-bed dedicated facility will provide on-site individual case planning with a focus on female clients through evidence-based, gender-responsive treatment and case management. |

| SUPPORTED EMPLOYMENT | Employment specialists help people with mental health conditions find and retain competitive jobs by helping them to identify positions that fit their skills and interests and by providing ongoing employment support (e.g., interpersonal skills training, identifying needed accommodations). | “[Supported employment] programs help facilitate several important components of the recovery process, including developing personal agency, meeting functional needs, and increasing social activity and feelings of belongingness. Thus, in addition to improving employment outcomes, supported employment programs have been linked to improvements in behavioral health symptoms, quality of life, self-esteem, and social functioning.”36 | • SITE: Durham County, NC • STATUS: FY2019 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: The University of North Carolina is expanding a specialty mental health probation services supported employment program and will provide services in two counties to people, particularly women, with high risks and needs. The university will partner with the School of Social Work to assess the impact of the program on recidivism and revocations among defendants with severe mental illnesses using a randomized study design. |

JMHCP SITES: INTERVENTIONS, DESCRIPTIONS, & PROMISING APPROACHES

Intercept 5: Community Corrections

Below is a list of some of the interventions that jurisdictions can use at different intercepts (also known as points) along their criminal justice system. This list is not exhaustive and, while interventions are only listed at one intercept, many can be implemented at various points in the system.

|

Intervention |

Description | Rationale |

Example Site |

| ACCESS TO COMMUNITY CORRECTIONS CENTERS (also known as reentry centers) | Community corrections centers are places where programming and services such as employment supports, mental health treatment, case management, and benefits navigation are co-located with the place where clients meet their supervision officers. | Community corrections centers are an emerging model meant to couple community supervision with services and programs that can help ensure people are sufficiently supported during their transition from the justice system back to the community. | • SITE: Denver, CO • STATUS: FY2013 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: The Probation and Parole Accountability and Stabilization Enhancement Center provides evidence-based interventions such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy, medication management, supported employment, and benefits navigation to adults on probation or parole who were charged with nonviolent offenses. These individuals have often also experienced homelessness and/or have mental illnesses, trauma, substance use conditions, and frequent contact with the justice system. |

| CONTINGENCY MANAGEMENT | Contingency management is an evidence-based behavioral therapy used most often to treat substance use disorders. In this model, a client’s positive behavior is rewarded or “reinforced” to promote recovery. For example, positive behaviors such as adhering to treatment regimens or refraining from using illegal substances may be rewarded with vouchers or tokens that can be exchanged for goods, services, or privileges. | “Contingency management techniques have demonstrated effectiveness in enhancing retention [in treatment] and confronting drug use. The use of vouchers and other reinforcers has considerable empirical support.”37 | • SITE: Charleston County, SC • STATUS: FY2009 JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: The Charleston County Mental Health Court used its JMHCP funding to, among other interventions, expand a contingency management system of rewards for positive behaviors. |

| PROGRESSIVE SANCTIONS | Progressive sanctions are structured, incremental responses to technical violations that may occur while someone is under community-based supervision. These sanctions are applied with the knowledge that people with mental illnesses may experience difficulties responding to supervision requirements. | Progressive sanctions are more effective than incarceration or other harsh penalties when responding to technical violations as they are often a result of a person’s mental health symptoms or side effects of psychotropic medications.38 | • SITE: Montgomery County Common Pleas Juvenile Division, OH • STATUS: FY2017 JMHCP Implementation & Expansion grantee • DESCRIPTION: The Montgomery County Mental Health Treatment Court (MHTC) supports up to 25 youth with moderate to high recidivism risk who have mental illnesses and/or substance use disorders to reduce recidivism and increase their connection to mental health treatment while also improving public safety. The Montgomery County Juvenile Court established a diversion protocol through the creation of an MHTC docket with sanction options and an array of available evidence-based treatment services. |

| SPECIALIZED MENTAL HEALTH CASELOADS | Community corrections officers supervise smaller caseloads of clients with mental health conditions. These officers receive additional mental health training to help them better respond to, and meet, the needs of their clients and reduce the likelihood of technical violations. This includes being aware of, and knowing how to connect their clients to, community-based treatment services. | Specialized mental health caseloads are more effective than traditional supervision in linking people with treatment services, improving their well-being, and reducing their risk of probation violations.39 | • SITE: Bexar County, TX • STATUS: FY2020 Juvenile JMHCP grantee • DESCRIPTION: The Bexar County Juvenile Board, in partnership with the Juvenile Probation Department and Center for Health Care Services, will develop a mental health reentry court with specialized supervision caseloads, targeted case planning, home-based case management family liaison assistance, and more. |

This brief was supported by Grant No. 2019-BX-K001, awarded by the Bureau of Justice Assistance. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the Department of Justice’s Office of Justice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Institute of Justice, the Office of Juvenile Justice and Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the Office for Victims of Crime, and the Office of Sex Offender Sentencing, Monitoring, Apprehending, Registering, and Tracking (SMART). Points of view or opinions in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice.

Endnotes

- This description was provided by the Colorado Division of Criminal Justice as part of their project narrative for the FY2019 JMHCP application. See also, Academic Training to Inform Police Responses, “Transforming Dispatch and Crisis Response Services: Meeting Challenges with Innovation” (webinar transcript, March 2, 2021), https://www.theiacp.org/sites/default/files/MHIDD/Academic%20Training%20Dispatch%20and%20Crisis%20Response%20Webinar_Transcript.pdf.

- Melissa S. Morabito et al., “Police Responses to People with Mental Illnesses in a Major U.S. City: The Boston Experience with the Co-Responder Model,” Victims and Offenders 13, no.8 (2018): 1093–1105.

- Policy Research Associates, The Sequential Intercept Model: Advancing Community-Based Solutions for Justice-Involved People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders (New York: Policy Research Associates, 2018), https://www.prainc.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/PRA-SIM-Letter-Paper-2018.pdf.

- Bureau of Justice Assistance, “Research to Improve Law Enforcement Responses to Persons with Mental Illnesses and Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities” (webinar, Vera Institute of Justice, New York, July 2019).

- Michael T. Compton and Amy C. Watson, “Research to Improve Law Enforcement Responses to Persons with Mental Illnesses and Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities” (PowerPoint presentation, 2019).

- Houston Police Department Mental Health Division, 2020 Annual Report (Houston: Houston Police Department, 2020), https://www.houstoncit.org/annual-report/.

- Michael T. Compton and Amy C. Watson, “Research to Improve Law Enforcement Responses to Persons with Mental Illnesses and Intellectual/Developmental Disabilities” (PowerPoint presentation, 2019); and Stephen Puntis, et al., “A Systematic Review of Co-Responder Models of Police Mental Health ‘Street’ Triage,” BMC Psychiatry 18, no. 1 (2018): 256.

- The EDGE program, Boulder County’s CRT, is a collaboration between the Boulder Sheriff’s Department, the City of Boulder, and Mental Health Partners in Colorado. Email correspondence between The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center and Mental Health Partners, September 14, 2020. See also, Frank Cornelia and Moses Gur, “Early Diversion for Individuals with Mental Illness” (PowerPoint presentation, Colorado Behavioral Healthcare Council, September 8, 2016)

- Treatment Advocacy Center, “Road Runners: The Role and Impact of Law Enforcement in Transporting Individuals with Severe Mental Illness, A National Survey,” 2019.

- Laura Alexander, outcomes coordinator of Advantage Behavioral Systems, email message to the CSG Justice Center, April 30, 2021.

- Amy C. Watson, M.T. Compton, and J.N. Draine, “The Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Model: An Evidence-Based Policing Practice?” Behavioral Sciences & the Law 35, no’s 5–6 (2017): 431–441.

- M Sitney and D Elliot, Justice and Mental Health Collaboration Program: Outcomes Associated with the Creation of the Gresham Service Coordination Team (Gresham, OR: City of Gresham, 2020), https://multco-web7-psh-files-usw2.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/Gresham%20Final%20Outcomes%20Report_11.17.pdf.

- Hayne Dyches, et al, “The Impact of Mobile Crisis Services on the Use of Community-Based Mental Health Services,” Research on Social Work Practice 12 no. 6 (2002): 731–751.

- Lt. Troy Siewert, email message to author, January 2021. See also Yasmeen Sheikah, “Orland Park Police Announce New Mental Health Response Program,” Patch News, December 9, 2020, accessed January 21, 2020, https://patch.com/illinois/orlandpark/orland-park-police-announce-new-mental-health-response-program.

- See Jackie Lacey, Mental Health Advisory Board Report A Blueprint For Change (Los Angeles County, CA: District Attorney County of Los Angeles, 2015), 39, http://da.lacounty.gov/sites/default/files/policies/Mental-Health-Report-072915.pdf.

- James M. Anderson, Maya Buenaventura, and Paul Heaton, “The Effects of Holistic Defense on Criminal Justice Outcomes,” Harvard Law Review 132, no. 3 (2019): 819–893, https://harvardlawreview.org/2019/01/the-effects-of-holistic-defense-on-criminal-justice-outcomes/.

- Texas Indigent Defense Commission, Texas Mental Health Defender Programs (Austin, TX: Texas Indigent Defense Commission, 2018), 11, http://www.tidc.texas.gov/media/58014/tidc_mhdefenders_2018.pdf.

- The CSG Justice Center, Behavioral Health Diversion Interventions: Moving from Individual Programs to a Systems-Wide Strategy (New York: the CSG Justice Center, 2019), 2, https://csgjusticecenter.org/publications/behavioral-health-diversion-interventions-moving-from-individual-programs-to-a-systems-wide-strategy/.

- Henry J. Steadman and M. Naples, “Assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for persons with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders,” Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 23 (2005): 163–170.

- “Community Event to Recognize Efforts in Reducing Number of People with Mental Illness in Douglas County Correctional Facility” (Douglas County, Kansas, County Administration press release, April 29, 2020), https://www.douglascountyks.org/depts/administration/county-news/2019/04/29/community-event-recognize-efforts-reducing-number-of.

- Christopher Lowenkamp, Marie VanNostrand, and Alexander Holsinger, Investigating the Impact of Pretrial Detention on Sentencing Outcomes (New York: The Arnold Foundation, 2013), 1–21. See also, Hallie Fader-Towe and Fred C. Osher, Improving Responses to People with Mental Illnesses at the Pretrial Stage: Essential Elements (New York: the CSG Justice Center, 2015).

- The CSG Justice Center, In Focus: Implementing Mental Health Screening and Assessment (New York: the CSG Justice Center, 2018), https://stepuptogether.org/wp-content/uploads/In-Focus-MH-Screening-Assessment-7.31.18-FINAL.pdf

- Personal communication between the CSG Justice Center and Hinds County Detention Center, October 2019.

- David S. Buck et al., “Best Practices: The Jail Inreach Project: Linking Homeless Inmates Who Have Mental Illness with Community Health Services,” Psychiatric Services 62, no. 2 (2011): 120-122, https://ps.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/ps.62.2.pss6202_0120.

- Anna Pecoraro and George E. Woody, “Medication-assisted treatment for opioid dependence: making a difference in prisons,” F1000 medicine reports 3, no.1 (2011), https://doi.org/10.3410/M3-1.

- Email communication between the CSG Justice Center and Franklin County, MA, October, 2019.

- David Cloud and Chelsea Davis, Treatment Alternatives to Incarceration for People with Mental Health Needs in the Criminal Justice System: The Cost-Savings Implications (New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2013), https://www.vera.org/downloads/Publications/treatment-alternatives-to-incarceration-for-people-with-mental-health-needs-in-the-criminal-justice-system-the-cost-savings-implications/legacy_downloads/treatment-alternatives-to-incarceration.pdf.

- G. Cattabriga et al, “Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) training for correctional officers: An evaluation of NAMI Maine’s 2005-2007 expansion program” (unpublished manuscript, December 21, 2007), PDF.

- Patricia Seppanen, Kathleen Westerhaus, and Chris Bray, Mental Health De-escalation Training Final Evaluation Report (Minnesota Department of Corrections, 2018).

- Tasseli McKay et al., Health Coverage and Care for Reentering Men: What Difference Can It Make? (Research Triangle Park, NC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016), https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/198726/justicebrief.pdf.

- These navigators were trained in the SSI/SSDI Outreach, Access, and Recovery (SOAR) program which is designed to increase access to SSI/SSD for people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. See, “What is Soar?,” Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), accessed October 10, 2019, https://soarworks.prainc.com/content/what-soar.

- Orion Mowbray et al., An Evaluation of the Alcovy Circuit Mental Health Court from 2013-2017 (Athens, GA: University of Georgia School of Work, 2018).

- Cynthia W. Morris, et al., Dimensions: Peer Support Program Toolkit (Aurora, CO: University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus School of Medicine, 2015), https://www.bhwellness.org/toolkits/Peer-Support-Program-Toolkit.pdf.

- SAMSHA, Forensic Assertive Community Treatment (FACT): A Service Delivery Model for Individuals with Serious Mental Illness Involved With the Criminal Justice System (Washington, DC: SAMHSA), https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/508_compliant_factactionbrief_0.pdf.

- Tasseli McKay et al., Health Coverage and Care for Reentering Men: What Difference Can It Make?

- Margarita Alegría et al., “Increasing Employment May Improve Mental and Physical Health for Individuals with Mental Health Challenges,” SAMHSA’s GAINS Center for Behavioral Health and Justice Transformation, March 29, 2018, accessed October 10, 2019, https://www.prainc.com/race-equity-p3/.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons With Co-occurring Disorders,” Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 42 (2005): 1–577.

- Lauren Babchuk et al., “Responding to Probationers with Mental Illness,” Federal Probation 76, no. 2 (2012): 1–15, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/1203/c16be0efe4ab513368103e8624a08afc471e.pdf.

- Jennifer L. Skeem and Jennifer Eno Louden, “Toward Evidence-Based Practice for Probationers and Parolees Mandated to Mental Health Treatment,” Psychiatric Services 57, no. 3 (2006): 333–342, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.57.3.333.

The sharp rise in school shootings over the past 25 years has led school officials across the U.S.…

Read MoreA three-digit crisis line, 988, launched two years ago to supplement—not necessarily replace—911. Calling 988 simplifies access to…

Read More Taking the HEAT Out of Campus Crises: A Proactive Approach to College Safety

Taking the HEAT Out of Campus Crises: A Proactive Approach to College Safety

The sharp rise in school shootings over the past 25 years has…

Read More From 911 to 988: Salt Lake City’s Innovative Dispatch Diversion Program Gives More Crisis Options

From 911 to 988: Salt Lake City’s Innovative Dispatch Diversion Program Gives More Crisis Options

A three-digit crisis line, 988, launched two years ago to supplement—not necessarily…

Read More Matching Care to Need: 5 Facts on How to Improve Behavioral Health Crisis Response

Matching Care to Need: 5 Facts on How to Improve Behavioral Health Crisis Response

It would hardly be controversial to expect an ambulance to arrive if…

Read More