Emerging Practices to Elevate and Replicate Community Responder Programs Nationwide

Expanding First Response National Commission Report

With growing calls for changes in how jurisdictions approach public safety, community responder programs are becoming more prevalent throughout the country, and even across the globe, as alternative first responses to situations that do not require an armed officer. Yet minimal research exists on definitive best practices for communities to follow when implementing and sustaining these programs. Based on a first-of-its-kind national commission focused on community response, this report details some of the emerging practices that program leaders can use to elevate and replicate community responder programs nationwide. Photo courtesy of Olympia Crisis Response Team.

Emerging Practices to Elevate and Replicate Community Responder Programs Nationwide

Expanding First Response National Commission Report

The Behavioral Health Emergency Assistance Response Division (B-HEARD) launched in New York City as a pilot program in June 2021.

Introduction

With growing calls for changes in how jurisdictions approach public safety, community responder programs are becoming more prevalent throughout the country, and even across the globe, as alternative first responses to situations that do not require an armed officer.1

Yet minimal research exists on definitive best practices for communities to follow when implementing and sustaining these programs. This lack of definitive best practices has left program and community leaders burdened with creating programs using information they can gather and deem trustworthy, leading to inconsistent and siloed efforts that are not executed or scaled up as easily or quickly as they could be.

It has also sometimes created burdens on existing programs, who are inundated with requests to share their experiences and support newer programs as they launch.

To support communities in expanding their first response efforts, The Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center launched a groundbreaking toolkit in 2022, Expanding First Response: A Toolkit for Community Responder Programs, as a central resource hub for communities and states looking to establish and strengthen community responder programs. This toolkit continues to offer tips, practical strategies, and examples of implementation, as well as an assessment tool to help communities determine where they are in planning, implementing, and sustaining community responder programs and then identify their next steps.

Recognizing that existing and future programs need standard practices to use as a foundation for effective and high-quality programs, the CSG Justice Center established a first-of-its-kind national commission focused on community response in 2023. The commission members represent a diverse cross-section of community responder programs, researchers, advocates, and policymakers nationwide. Collectively, these experts—who are deeply familiar with the necessary elements of community responder programs—used practiced-based evidence to identify emerging practices4 for professionals interested in uplifting and expanding community response.

CSG Justice Center staff worked closely with the commissioners to identify and share these emerging practices with the field. Staff also documented the process of establishing and facilitating the commission to help communities create a commission of their own (or group of diverse decision-makers) to drive their initiatives. This report first explains the process of establishing the Expanding First Response National Commission and then details the emerging practices that program leaders can use to elevate and replicate community responder programs nationwide.

The Albuquerque Community Safety Department launched in September 2001 with three teams of responders operating throughout the city.

Community Responder Program Overview

Although the term “community responder program,” is relatively new, the concept of sending trained health professionals as first responders has been around for decades.2 These programs have evolved over time into what now typically involves mobile teams staffed by professionals trained in behavioral health de-escalation, assessment, and response who are able to respond to 911, emergency, or urgent calls for service. They often provide immediate assistance to people experiencing behavioral health crises (such as mental illness, substance use, or an overdose), poverty-related support, welfare and wellness checks, assistance with housing needs, and de-escalation of minor disputes.

The response provided by community responder teams varies, yet typically includes de-escalation, conflict resolution, needs assessment (such as suicidality and substance use disorder), mental health interventions (like motivational interviewing), and connection to treatment, support services, and other resources. Teams can also include emergency medical technicians or paramedics who provide physical assessments and appropriate medical support as part of the response. Some community responder teams will follow up with people after the initial response to provide additional connections and resources or even ongoing case management.

Beginning in 2020, and especially following the murder of George Floyd, several communities began implementing community responder programs in an effort to reduce reliance on law enforcement and improve community trust in first responders.3 Through increased public awareness, scrutiny, and advocacy—mostly led by grassroots activists, health professionals, and community members—community responder programs have emerged as a strategy that people from all walks of life see as an important mechanism for supporting people in need. In fact, many of these programs are often supported and funded by police and fire departments.

Community members and local leaders agree that long-term success depends on the program being built into a comprehensive continuum of care and support. This continuum ensures that after community responder programs provide immediate care, they can connect people to housing, treatment, benefits, employment, and more—resources that bolster a person’s well-being far into the future. Several communities are leading the way, implementing various community responder models tailored to their local needs. To learn more about these programs and find essential resources for successful implementation, visit the Expanding First Response Toolkit.

Methodology

Building the Expanding First Response National Commission

Launched in 2023, the CSG Justice Center established the Expanding First Response National Commission to help shape the conversation on and offer recommendations for advancing community responder programs in communities across the nation. Through collaboration and communication with known community responder programs, CSG Justice Center staff, partners, funders, experts, and national training and technical assistance providers identified and invited a nationally representative group of experts to serve as members of the commission. The commission was made up of 21 experts, including practitioners, researchers, advocates, and policymakers from across the country, representing the locations, models, identities, expertise, and experiences of community responder programs nationwide. All commissioners had firsthand experience working directly with, or a deep understanding of, community responder models.

From February through July 2023, the commissioners met monthly over Zoom. CSG Justice Center staff and guest speakers facilitated conversations and discussions for 90 minutes each, covering a range of topics related to community response. During each meeting, commissioners gave or listened to presentations, participated in open discussions and break-out groups, and used Slido polls (a Q&A and polling platform for live and virtual meetings and events) to provide their immediate feedback on the topics. Members also provided additional input via email and monthly feedback surveys.

Identifying Emerging Practices

Using consensus building methods, the 21 commissioners identified emerging practices to elevate and expand first response with community responder programs. As commissioners shared their insights, CSG Justice Center staff gathered the information using hand-typed notes, Slido polls, discussions in the Zoom chat, and audio recordings. After each meeting, staff emailed commissioners a SurveyMonkey questionnaire, inviting them to respond with any additional insights on the topic they discussed that month. The staff reviewed these data and coded the responses to identify emerging practices that communities nationwide could use to support their local efforts, and then distributed the findings to the commissioners for feedback. Once finalized, staff used the findings to craft the emerging practices highlighted in this report.

Olympia, WA’s Crisis Response Unit provides free, confidential, and voluntary crisis response assistance.

Emerging Practices for Community Responder Programs

Atlanta’s Policing Alternatives & Diversion Initiative addresses community concerns related to unmet mental health needs, substance use, and extreme poverty.

Commissioners and CSG Justice Center staff organized the emerging practices into four pillars, intended to help set a standard for high-quality programming that meets the unique needs of communities, no matter location or size.

1. Building and maintaining a professional identity with the community

2. Integrating community response into existing call centers5 and first response methods

3. Scaling community responder programming with funding

4. Managing and monitoring a program’s quality through data collection and use

“This work can’t be done well without involving community members, and particularly those community members most impacted by these systems.”

S. Rebecca Neusteter, commission member and executive director of the University of Chicago Health Lab in Chicago, Illinois

Although time constraints limited the topics and emerging practices that the commissioners could address, the ones identified in this report are critical components to the success of all community responder programs. Examples of programs that use these emerging practices effectively are shared throughout the report. For more information on these programs, visit the Expanding First Response Toolkit.

Crisis Assistance Helping Out On The Streets (CAHOOTS) has been operating in Eugene, OR for more than 30 years.

1. Building and maintaining a professional identity with the community

The development of a professional identity for community responder programs is critical to an effective response system that meets the needs of people and understands the historical context of the communities in which they work. Many of the commissioners noted that decades of disinvestment from community-based care, as well as structural and institutionalized racism, have contributed to the criminalization of mental illness, substance use, homelessness, poverty, and the disproportionate representation of people of color in the criminal justice system.6

These legacies have led to several communities, but especially communities of color, having a deep mistrust and fear of emergency response systems. For community responder programs to effectively expand first response, they will have to build and maintain a professional identity centering on community trust. This will help ensure that people who need help are able and comfortable to call for it, which involves demonstrating

- Reliability and consistency in their responses, such as ensuring people receive the same quality of response regardless of which responder arrives;

- Visibility and transparency around their practices, such as by reporting their policies on responding to different call types and data on responses and outcomes to the public;

- Accountability for the health and well-being of community members, such as by ensuring all staff are aware of and have a relationship with service providers and resources to meet individual needs; and

- A culture of empathy and optimism through their partnerships, communication, and staffing, such as through a culturally responsive atmosphere that promotes positive partnerships, communication, and by responding to each person as an individual.

“Our team shows up at community events and celebrations, such as Pride, the 4th of July Parade, and the opening of the new library, so that we are not seen as scary, but involved in all aspects of the community.”

Annie Burwell, commission member and program manager of a Crisis Response Unit in Round Rock, Texas

Commissioners recommended programs use outreach efforts and ongoing communication that target different audiences to ensure a broad understanding of crisis responses available in a community. Programs can also partner with and rely on others to spread the word, such as with credible messengers7 and community-based organizations, system leaders and partners, previous service recipients, and even marketing experts. Prioritizing outreach and engagement will raise awareness of community responder programs especially when programs target the type of outreach to different audiences. For example, communities can:

- Create public service announcements, such as billboards, pamphlets, posters, news segments, and television ads;

- Post on social media, such as on Facebook, X (formerly known as Twitter), Instagram, and TikTok;

- Lobby legislators and community leaders for their public support and supportive legislation; and

- Attend existing community events, such as festivals and parades, as part of their initial and ongoing efforts.

Integral Care’s Expanded Mobile Crisis Outreach Team in Austin, TX, was established in 2013 and includes mental health professionals who respond to people experiencing a mental health crisis.

In addition to outreach and engagement, intentional recruitment, hiring, and ongoing training can create a balanced team of professionals who meet the needs of their community and help to maintain its professional identity. The staff of community responder programs drive its success. Therefore, commissioners recommended that leadership recruit and retain staff by clearly documenting and communicating expected roles and duties using resources, approachable supervision, and opportunities to observe and practice (including working with other first responders). In addition to ensuring an understanding of their roles, commissioners noted the importance of making certain that staff have clear lines of authority with other first responders and service providers, transparent and competitive compensation, personal and professional support (such as with comprehensive wellness programs), benefits (such as including generous paid time off and retirement planning), and career development opportunities (such as growth opportunities, mentorship, and training) to recruit and retain valuable staff.

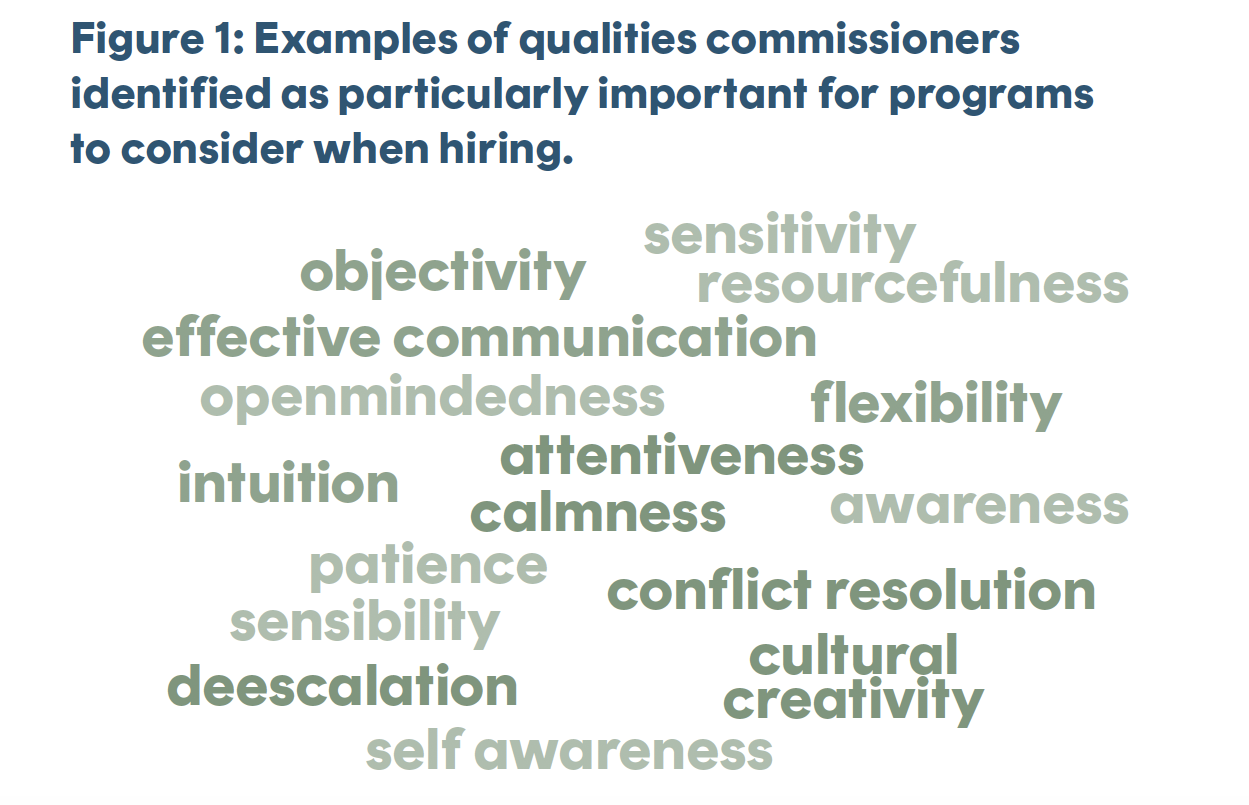

Recruitment and hiring practices and policies can look different across communities, but commissioners identified the qualities in Figure 1 that might ensure the role is the right fit for both the responder and the community. These qualities are typically indicators that responders will be emotionally intelligent, knowledgeable, connected to community resources, and will exemplify good judgment and patience. However, programs can determine which skills and qualities are most important for their community’s needs.

B-HEARD in NYC is operated jointly by the Fire Department of the City of New York’s Emergency Medical Services and NYC Health + Hospitals, with the Mayor’s Office of Community Mental Health providing oversight.

“Having a certification or license associated with community responders might be important. Law enforcement, fire, and EMTs have certifications. I think community responders could eventually have similar training and certifications to ensure respect as a fourth arm of response. But you’d have to hire people and give them time to get that certification while doing other work for the program. It is also important to have people formally involved in the systems and culturally congruent to those they serve. If there’s a combination where they have that background and get those certifications, it would be perfect.”

Retired Sheriff Dr. Currie Myers, commission member and retired sheriff from Johnson County, Kansas

Often, people with lived experience similar to the needs and experiences of the people served by community responder programs have the necessary qualities and can be trained to build the required skillsets, such as de-escalation techniques and their ability to conduct assessments. Although many communities have successfully implemented programs prioritizing clinical education and credentials, others have successfully leveraged lived experience and on-the-job training to build their teams and maintain a positive professional identity with the community.

Although commissioners noted that each approach is useful, they urged programs to incorporate community responders with lived experiences who are from the communities they serve to build trust with community members and best provide services to them. It is important to note that many existing hiring policies limit the ability of people with lived experience in the criminal justice system, substance use disorders, and so on, from becoming community responders and leaders. Thus, commissioners reported that it is imperative leaders review existing policies and revise them before hiring program staff.

In addition to the necessary qualities, staff need specific knowledge and skills. To ensure staff have the necessary knowledge and skills to respond to people in need, commissioners identified the following training and resources:

- Staff and public safety awareness, such as legal and ethical practices; tips for scene safety; situational awareness training; protocols for wearing personal protective equipment; effective collaboration practices with other first responders like the police department, fire department, and emergency medical services; disaster response policies; incident command system structures and policies, and ways to best use communication and radio equipment.

- Multidisciplinary skills training, including on behavioral health assessment, response, and resources; first aid and cardiopulmonary resuscitation certification, de-escalation tactics, motivational interviewing, diagnostic processes, trauma-informed care, harm reduction, emotional intelligence, signs of child abuse or neglect, signs of human trafficking or sexual assault, and diversity equity inclusion principles and best practices.

- Staff wellness, including through in-house counseling, regular team check-ins, clinical and/or professional supervision, and employee support programs.

- Information about local resources and contexts to be able to offer service recipients informed and accurate details, such as tips on navigating the geography, existing service providers and housing, and cultural preferences of community members.

“People with lived experience often want to give back to their communities—and already have those relationships intact—so [employing them as community responders] would be a great way to use those relationships and really serve the community they came from.”

Brittany Lovely, commission member and systems change consultant from Washington, D.C.

2. Integrating community response into existing call centers and first response methods

Community responder programs can be housed in various operations, including service provider organizations, existing government agencies (such as public safety or fire departments), or even as a newly created agency. However, one constant is that they cannot operate in a vacuum. Traditional first response models such as police departments, fire departments, and emergency medical services already exist in communities, therefore community responder programs will need to partner with these agencies in order to be effective in responding to the needs of the community.

As community responders integrate into and expand first response options, each of these entities will need to work together to maintain a comprehensive continuum of care8 that meets the needs of communities equitably.

However, community responders should be careful not to position themselves as the sole solution to other systems’ disparities and challenges. Instead, commissioners recommended building and maintaining an individual professional identity that adds to a continuum of care.

To effectively integrate these teams into the existing systems, community responder programs must have a way to identify and respond to appropriate calls, whether through 911 or other call centers (such as 988, 211, 311, and other call lines). This includes building awareness among existing call center staff to ensure they are knowledgeable about the purpose of community responders and the types of calls they are well-suited to address. Programs can increase awareness and understanding by creating cross-agency training to teach call center staff about the history and effectiveness of community responder programs, as well as approaches to integrating community responders into call receipt and dispatch processes. They can also work with community leaders to offer opportunities for call center staff to engage with community responders in and out of the field and create clear protocols to follow when determining call appropriateness for community responder programs.

The Portland Street Response Team is a trauma-informed community response team embedded within Portland’s Fire and Rescue Department.

Baltimore’s Behavioral Health 911 Diversion Program is housed within the city’s emergency response network and is a partnership between Behavioral Health System Baltimore and Baltimore Crisis Response, Inc.

When creating policies and procedures for identifying appropriate calls for community responder programs,9 commissioners identified multiple factors that should be considered, such as state, regional, and local policies and regulations, liability protections for people answering and dispatching calls, safety (of staff, the person in need, and the surrounding community), capacity of responders, available resources, the wants and needs of the individual, and the wants and needs of the community. With those in mind, community responder program leaders can work with others to develop clear processes to test and improve the quality and consistency of call identification and dispatch.

Like community responder staff, call center staff need quality onboarding and ongoing training and resources to be effective partners in this integration. Training and information critical to ensuring the appropriate call receives the appropriate response can include introductions to:

- Behavioral health topics and responses, such as substance use disorder and mental illness, suicide risk assessment and harm reduction approaches;

- Traditional emergency response topics and resources, such as Crisis Intervention Team training and de-escalation;

- Cultural competency training, such as increasing self-awareness, understanding others’ cultural identities, and culturally and linguistically appropriate interventions; and

- Updated information on resources callers can be connected to over the phone or by responders, such as 988, crisis and respite centers, food banks, homeless shelters, immigration supports, and telehealth providers.

Commissioners also recommended that programs set reasonable expectations for call response times— another component of trust building—so that call takers can accurately communicate expected response times to callers and community responders can set achievable benchmarks in their responses. Commissioners noted that programs should work with local leaders to consider multiple factors as they set these expectations, such as available resources and information, capacity of responders, location of the call, needs of the individual, policies, safety, urgency, and weather and traffic conditions.

3. Scaling community responder programming with funding

Establishing and sustaining a community responder program requires multiple perspectives, especially when choosing the appropriate model to build and the funding sources to sustain it. Figure 2 shows examples of the voices that commissioners recommended programs include in this decision making.

Each partner’s roles, identities, and experiences will likely overlap, which can increase representation from the community that the program serves. Involving each as early as possible opens programs up to creative approaches and solutions to community and program needs. Also, commissioners noted that in communities where a labor union represents current first response personnel, work cannot simply be taken away from them and given to a different response system. Therefore, programs should include labor unions in program development discussions as early as possible to ensure the program is accepted and supported as an additional resource to an overburdened system rather than a replacement.

In addition to diverse decision-makers and supporters, scaling a community responder program requires initial and ongoing funding, which can sometimes be challenging to secure. The amount and sources of funding needed will look different depending on the agency or organization that manages it, the community responder model, and the needs and size of the community. When determining the amount of funding needed and for what parts of the program, community responder leaders should factor in radios, vehicles, uniforms, marketing activities, wellness programs, and training, in addition to traditional budget components such as staffing and fringe, direct and indirect costs, and insurance/liability coverage needs.

Upkeep and regular updates to these items should inform any sustainability plans for community responder programs. Some of the funding sources that commission members identified are:

- Federal, regional, and state funding, such as community mental health services block grants, substance use prevention and treatment block grants, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration grants, opioid response grants, Department of Justice funding, and Department of Housing and Urban Development Community Development Block Grants;

- Insurance, including Medicaid, Medicare, managed care organizations, and commercial insurance;

- Medical system partnerships;

- Municipal bonds;

- Philanthropic funds; and

- State and local funding and taxes, by way of state and local grants, budgets, tax levies, sales taxes, vice taxes, general taxes, and surcharges.

“Not all organizations are built the same, and they do not respond to or are responded to by the community in the same way.”

Reverend Dr. Charles Boyer, commission member and co-founder of Salvation and Social Justice in Trenton, New Jersey

The San Francisco Street Crisis Response Team was founded November 2020 to provide trauma-informed clinical interventions and care coordination for people experiencing behavioral health crises.

4. Managing and monitoring a program’s quality through data collection and use

Data collection and analysis are critical to ensuring community responder leaders establish a high quality program that meets the community’s needs, functions as intended, and is maintained over time. Programs that regularly monitor their processes using data can consistently improve their efforts over time, making them not only more sustainable but more valuable to the community as a resource. Additionally, programs can increase their options for sustainable funding by using data to show strong implementation and a positive impact on the community. Commissioners mentioned that including storytelling or testimony from people who receive services from the program, and their families, is extremely powerful and effective in conveying the program’s impact on the community to funders and legislators (for example, watch this video to learn how Salvation and Social Justice used the power of community visions and stories to drive change).

When designing a community responder program, collecting information on community members and their needs, such as health, well-being, socioeconomic level, community cultures and stigmas, existing system processes and gaps, and available services and resources will ensure that community responder programs understand the people they are serving, the best approaches and available resources for them, and the service gaps that the program can fill on the crisis continuum. Including information on the needs and preferences of community members early on, and then respectfully tracking their satisfaction with responses, is critical to ensuring community responder programs remain human centered and high quality. Equally as important is collecting information on existing and missing partnerships to the community responder program to break down siloed information and work to improve coordination and collaboration across a crisis and care continuum.

“[I recommend sharing] stories of how cost savings to municipalities can lead to more of what communities desire, like more parks, more health care facilities, improved public education, and before and after care programs. The best way to demonstrate how this will work and improve quality of life is through the storytelling of programs that are working. Tailor it to the specific city or town. People have to see and be moved by the stories and faces of the program, even if it’s an animation. Put faces, even actors’ faces, to what the work looks like and why it is helping the viewer’s quality of life.”

Tansy Mcnulty, commission member and founder and CEO of 1 Million Madly Motivated Moms in Washington, D.C

Regularly collecting information on the community responder program’s implementation and outcomes is also essential to ensuring that the quality of the program is consistent over time and resources are being used efficiently. Implementation and process evaluations can be as helpful as outcomes and impact evaluations because they offer comprehensive insights on programmatic processes, impacts, and needed improvements. Further, qualitative data can be equally as valuable as quantitative data because qualitative data can contextualize and elaborate on the information provided by quantitative data.

Although formal program evaluations will inform the field and increase supportive funding and policies, ongoing information gathering, even informally, can assist programs in building and maintaining the quality of the program. Regardless commissioners agreed that collecting different types of data is essential to measuring and ensuring success, including information on:

- The crisis calls and calls for service, such as nature of the call, reported need or emergency, indication if it is a “familiar face,”10 type of response dispatched, and response time, will help community responder programs understand the types of calls received and whether the program is responding to all appropriate calls or if there are gaps.

- The response, such as calls missed or declined, characteristics of the person in need, their wants and needs, responses and resources provided, resources and services needed but not provided, location details, additional responders and any use of force, call resolution, and any follow up activities, can inform the program on community needs and how the community responder program currently meets those needs and can continue to do so.

- The response outcomes, such as arrests and jail admissions; client, community, and staff satisfaction; emergency room admissions; hospitalizations; follow-up treatment and service use; and transportation details, can inform the program about how their response is impacting the people in need, even after the initial response, and whether it is having the intended impact on the community.

- Program operations, such as needed and used equipment, staff, and supplies; existing and needed staff training, education, and credentials; and funding sources, will ensure the program represents the community it serves and that leadership knows what funding exists and is needed, what staff exist and are needed, and what support and wellness resources exist and are needed to maintain the quality and impact of the program while ensuring the well-being of the program and its staff.

Note: Although system administrative data, such as 911, police, criminal history, and hospital records, are valuable and essential to track implementation and outcomes, such sources may also include reporting errors or lack context, leading to biased conclusions against historically marginalized groups.11 As such, managing and monitoring program quality through multiple data types and sources is imperative to ensure data is accurate and contextualized before any analysis can inform program decisions. Other sources of data can include community and system leaders and staff, first responders, funders, members of the public, service providers, system partners, and service users and their families. Including various sources of data will help community responder programs better understand what is working and what changes are needed to continuously improve upon their efforts.

It is important for programs to be intentional when identifying what exactly to measure and how to measure it by including program staff, partners, and other community members in the decision-making process. Doing so can look like establishing a diverse committee of decision-makers, hosting town halls and listening sessions, conducting surveys, and other formal and informal opportunities for all people involved or impacted by the program to provide insight and opinions. When deciding what to measure, this collaboration can ensure that the definition of program success is understood and agreed upon by those doing the work and receiving support.

Once communities determine what information to collect, they can lessen the burden on the people who provide the needed information by customizing data collection methods that are convenient and comprehensive. For example, communities can use data collected from interviews, focus groups, surveys, feedback forms, and observations to elaborate on and contextualize shared administrative data so that programs better understand the complete picture of processes and outcomes and can identify needed improvements. This might look like interviewing people who called for or received support from a community responder team to learn if they felt the response time, response type or service provision, or resolution was satisfactory and positively impactful. Creating options for people to provide anonymous and confidential feedback can also increase participation and reduce fears of retaliation or consequences.

“We need mechanisms for getting in-depth feedback from community stakeholders and practitioners.The clinicians, the paramedics, and the police officers doing this work have a front row seat to some of the deficiencies that may exist at a systemic level. It is important to listen [while trying] to affect change, because [the people doing this work] will become just as frustrated with a perceived lack of change as the community.”

Andrew Dameron, commission member and director, Emergency communications for the City and County of Denver, Colorado

Complete and accurate qualitative and quantitative data, from a variety of sources, can be used to improve and sustain a community responder program by:

- Ensuring staff training and education align with needed responses;

- Ensuring the proper response is provided at the right time;

- Establishing goals and performance metrics and tracking progress;

- Identifying and tracking funding sources, opportunities, and requirements;

- Identifying and understanding disparities in responses and services;

- Monitoring adherence to local, state, and federal regulations;

- Pinpointing if and how current responses and services meet people’s needs;

- Tracking needed versus available resources (staff, equipment, supplies); and

- Tracking partnerships and identifying missing links.

Publicly sharing data (such as through dashboards or presentations) and creating ongoing feedback opportunities among the people providing data, the people collecting and analyzing data, and the people using the data will build community trust and ensure that any conclusions are contextualized, complete, and accurate.

Conclusion

In just six months and six hours of meetings, the Expanding First Response commissioners identified numerous emerging practices across the four pillars to be used as benchmarks by programs. However, this work is evolving daily, and more work remains to establish guidelines of best practice for the field. To this end, the CSG Justice Center will continue bringing together multidisciplinary experts representing community responder programs throughout the country and partnering with existing programs to provide resources and information that can help effectively and efficiently expand first response in local areas. To learn more and stay abreast of these efforts, visit the Expanding First Response toolkit.

Denver’s Support Team Assisted Response program was formed as part of a partnership among the Denver Police Department, local health agencies, and community stakeholders.

Endnotes

1. See examples of programs listed in Community Safety Workgroup, Directory of Alternative Crisis Response Programs (Indivisible Eastside, 2023); Reach Out Response Network, Final Report Summary on Alternative Crisis Response Models for Toronto (Toronto, Canada: Reach Out Response Network, 2020); Community Crisis Response Team (CCRT), Building Suicide-Safer Communities (Limerick, Ireland: CCRT, 2016).

2. Kevin Hazzard, American Sirens: The Incredible Story of the Black Men Who Became America’s First Paramedics (Hachette Books, 2022), 336.

3. According to a Harvard University study released in 2020,“Black Americans are 3.23 times more likely than White Americans to be killed by police.” Statistics like this have historically resulted in Black, Indigenous, and other communities of color being reluctant to trust first responders of any kind. See, Gabriel L. Schwartz and Jaquelyn L. Jahn, “Mapping Fatal Police Violence Across U.S. Metropolitan Areas: Overall Rates and Racial/Ethnic Inequities, 2013-2017,” PLoS ON, 15 (2020): https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229686.

4. Emerging practices are new approaches that show promise yet do not have research supporting them as “best practices”.

5. Although most community responder programs receive crisis calls and calls for service through 911 call centers, others may receive calls through other call centers such as 988, 211, or 311. Additionally, 911 call receipt and dispatch processes vary by jurisdiction. To be inclusive of the nuances among programs and communities, the term “call center” is used in this report

to encompass all answering services that receive crisis calls and calls for service which community responder programs can partner with.

6. See for example, Amy C. Watson, Michael T. Compton, and Leah G. Pope, Crisis Response Services for People with Mental Illnesses or Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities: A Review of the Literature on Police-Based and Other First Response Models (New York: Vera Institute of Justice, 2019): Elizabeth Hinton and DeAnza Cook, “The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans: A Historical Overview,” Annual Review of Criminology, 4 (2021): 261-286, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-060520-033306; National Conference of State Legislatures, Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Justice System: The Legislative Primer series for Front-End Justice (Denver, Colorado and Washington, DC: National Conference of State Legislatures, 2022), 16, https://documents.ncsl.org/wwwncsl/Criminal-Justice/Racial-and-Ethnic-Disparities-in-the-Justice-System_v03.pdf; Sam McCann, Locking up People with Mental Health Conditions Doesn’t Make Anyone Safer (Vera Institute of Justice, 2022), https://www.vera.org/news/locking-up-people-with-mental-health-conditions-doesnt-make-anyone-safer.

7. Credible messengers are people who have been directly or indirectly impacted by the justice system, or have lived experience in other systems, and have become community agents of change, often guiding people in need to opportunities and resources they did not have themselves. This role may be formal or informal, but credibility must be determined by the community and the people a credible messenger serves.

8. For more information on crisis care and crisis systems, see “Roadmap to the Ideal Crisis System,” National Council for Mental Wellbeing, accessed December 12, 2023, https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/resources/roadmap-to-the-ideal-crisis-system/; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care: Best Practice Toolkit (Rockville, MD, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2020), https://www.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/national-guidelines-for-behavioral-health-crisis-care-02242020.pdf.

9. For examples of policies and procedures, see Amos Irwin and Rachael Eisenberg, Dispatching Community Responders to 911 Calls (Washington, DC: Center for American Progress, 2023), https://www.americanprogress.org/article/dispatching-community-responders-to-911-calls/.

10. The term “familiar face” is often used to describe individuals who frequently come into contact with law enforcement, jails, courts, crisis response, emergency departments, homeless services, and other behavioral health systems and who have complex behavioral health needs that no single local system or program adequately addresses. See “States Supporting Familiar Faces,” CSG Justice Center, accessed December 7, 2023, https://csgjusticecenter.org/projects/states-supporting-familiar-faces/; Samantha A. Zottola et al., “Understanding and Preventing Frequent Jail Contact,” in Handbook on Prisons and Jails, ed. Danielle Rudes et al., (New York: Routledge, 2023), 323–344, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003374893-27.

11. Sarah Lageson, “Criminally Bad Data: Inaccurate Criminal Records, Data Brokers, and Algorithmic Injustice,” University of Illinois Law Review (July 2023), https://ssrn.com/abstract=4503845; John W. Peabody et al., “Assessing the Accuracy of Administrative Data in Health Information Systems,” Med Care 42, no.11 (2004):1066–72, doi: 10.1097/00005650-200411000-00005.

Project Credits

Writing: Mari Bayer, Melissa McKee, and Ashtan Towles, CSG Justice Center

Research: Melissa McKee, Nina Richtman, and Ashtan Towles, CSG Justice Center

Advising: Anne Larsen and Sarah Wurzburg, CSG Justice Center

Editing: Darby Baham, CSG Justice Center

Design: Michael Bierman

Web Development: Yewande Ojo, CSG Justice Center

Public Affairs: Kevin Dugan, CSG Justice Center

Support for the Expanding First Response National Commission and this subsequent publication were provided by the Joyce Foundation, The Pew Charitable Trusts, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and Stand Together Trust. Points of view or opinions in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the aforementioned funders or The Council of State Governments.

About the authors

This May, the state of Washington passed legislation supporting the expansion of alternative response teams (sometimes called community…

Read MoreThe CSG Justice Center has partnered with the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency and CIT International to…

Read More Developing a Common Definition for Community Responder Programs

Developing a Common Definition for Community Responder Programs

This May, the state of Washington passed legislation supporting the expansion of…

Read More CSG Justice Center Launches First-of-Its-Kind Statewide Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) Technical Assistance Center

CSG Justice Center Launches First-of-Its-Kind Statewide Crisis Intervention Teams (CIT) Technical Assistance Center

The CSG Justice Center has partnered with the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime…

Read More